Interviews

CinemaBlend frequently sits down with the talent who are responsible for the movies, television shows, streaming features, and pop-culture moments that you want to be reading more about. From Tom Hanks to the cast of Avatar: The Way of Water, from the latest contestant on The Masked Singer to the cast of Yellowstone, CinemaBlend ample time for exclusive conversations with Hollywood's biggest stars.

And CinemaBlend prides itself on asking talent the questions that they aren't hearing from every other outlet, leading to passionate answers that are meant to educate and entertain you, our readers. If they are important in Hollywood, they are speaking with CinemaBlend.

Latest about Interviews

Kelly Marie Tran Reacts To Hilarious Star Wars Reference In Her Queer Rom-Com The Wedding Banquet

By Sarah El-Mahmoud published

Exclusives Rose Tico forever!

Ghosts’ Asher Grodman Told Me Why Trevor Had ‘No Right’ To Do What He Did After Learning About His Daughter, And I 100% Agree

By Riley Utley published

Exclusives Yeah, he really shouldn't have done that.

Charlize Theron Only Had One Line In Apple TV+'s The Studio. Why The Co-Creator Told Me It Was The 'Most Baller Thing Ever'

By Adam Holmes published

It definitely caught my attention.

Issa Rae Shared Her Opinion On How Hotel Reverie Wraps, And It Reminds Me Of Another Black Mirror Episode I Think Fans Misread

By Mike Reyes published

Exclusives Get ready to reopen some old emotional wounds, Black Mirror fans!

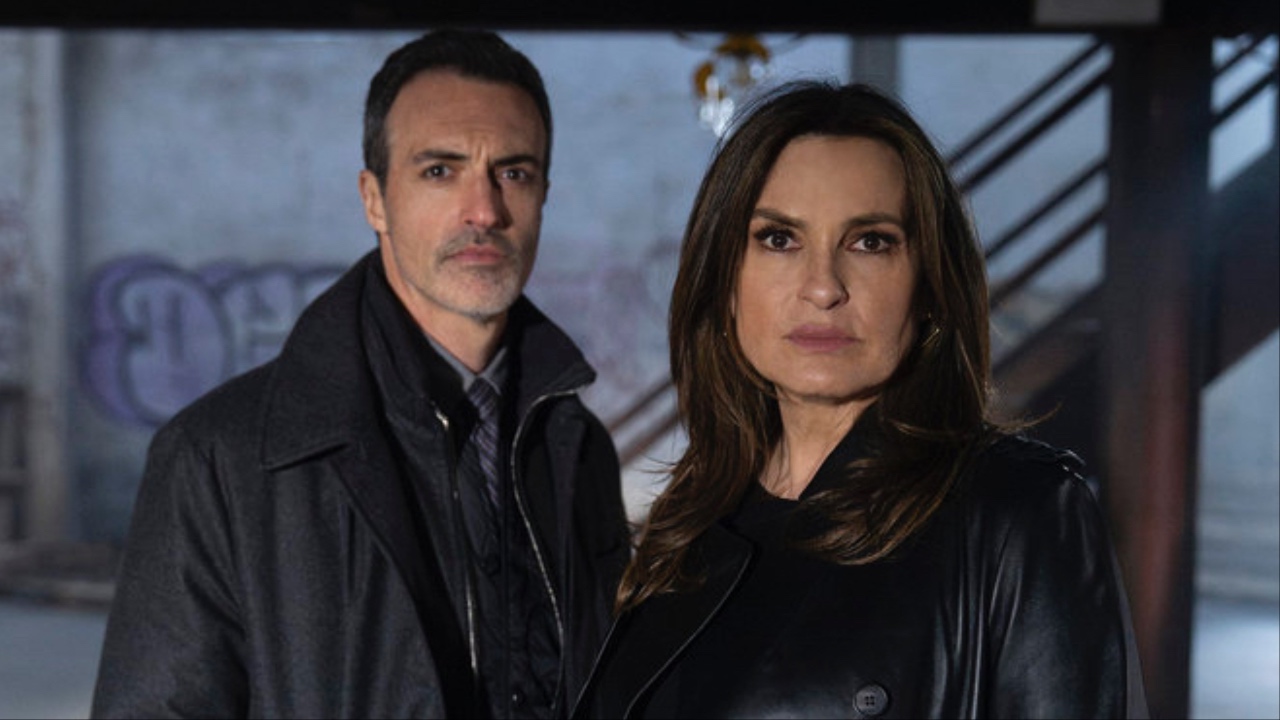

Law And Order: Organized Crime Star Told Us What's 'More Realistic' About Season 5 On Peacock, And Now Stabler's Accident Seems A Lot Scarier

By Laura Hurley published

Exclusives Dean Norris previewed the drama on the way for the Stabler family in Season 5.

Surprise Breakout Hit North Of North Cracked Netflix's Top 10, And The Lead Actress Shared How It Makes Her Feel

By Alexandra Ramos published

Such a hilarious show!

The Conners' Lecy Goranson Gave Me Her Thoughts On Putting Roseanne's Death Back In Focus For The Final Season

By Nick Venable published

Exclusives Only three episodes left!

‘You May Lose Your Fan Favorite’: Chicago Fire’s Eamonn Walker Explained How Serious The Crisis Had To Be To Bring In Boden, And I’m Nervous

By Laura Hurley published

Exclusives Boden is back, but he might not get the warmest welcome.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News