Steven Soderbergh On His Retirement, His Career, And His Childhood Shoplifting Phase

Last week we ran the first half of my incredibly long and fascinating roundtable interview with Steven Soderbergh, who has Haywire in theaters this weekend and Magic Mike coming out later this year. The previous part of the interview focused largely on Haywire, but the conversation was much wider-ranging than that, going over Soderbergh's early career, his childhood, his experience working in the often brutal studio system, and his plans for retirement, which he insists is still happening.

Read below for that part of the interview, and check out Haywire in theaters this now.

Is there anything you took away from the time you spent on The Hunger Games regarding the enormity of it? I assume it was bigger than any of the movies you've worked on.

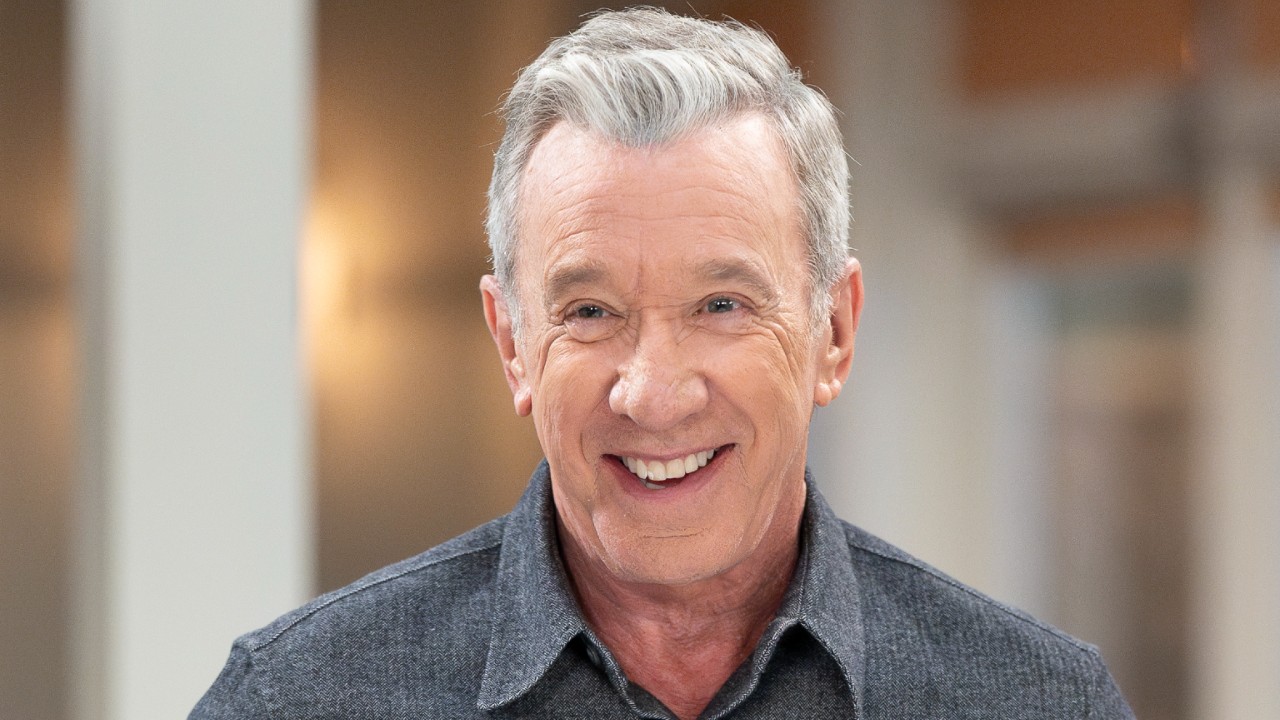

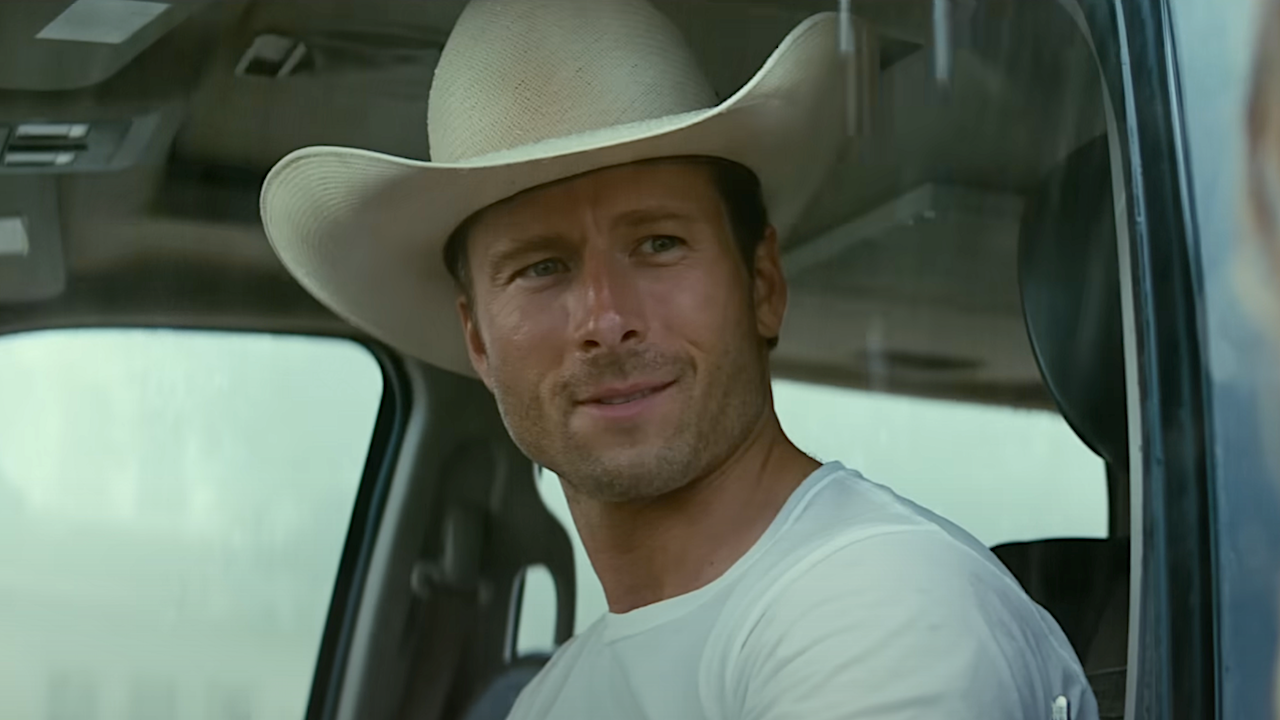

It wasn't any bigger than an Ocean's movie. I'm glad I wasn't directing it. My two days were pretty specific. And it was something Gary and I had talked about in March, because we've known each other a long time. He's done me a lot of favors. He's one of the people I call to show things to who doesn't hesitate to tell me what's wrong. To his credit, he offers to roll his sleeves up and be part of the solution. In March and April, when he got the board, he knew immediately-- "I've got two days at the beginning of August, second unit days, I'm going to need to hire someone to come and do these. What is your schedule going to be?" That was all done months ago. I felt bad for him that when I showed up, suddenly this became news and he had to give a statement. It was just sad that it can't just be "Oh, I'm doing a solid for my friend." There has to be a grassy knoll aspect to it.

What would 26-year-old you say about Haywire?

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

I think you know I would never sit around thinking about that. If you took me then and flash-forwarded me to now and showed me the list, showed me the list of films, I'd be really happy. Some of them represent things that were absolutely beyond my capability at that point. I'm a better filmmaker than I was then. My ability to problem-solve is better, my filtering capabilities are better. If you said to me "You're going to do all of that," I would have thought, "Wow, cool."

What would surprise you the most?

Probably the Ocean's films. I loved heist movies, I've always loved heist movies, but on a technical level that was something that, at that point, I would not have been able to pull off.

In the 10 years between sex, lies and Erin Brockovich, where were you personally in that time. DId you feel like you would never be able to have such a hit again?

You can read interviews with me during sex, lies when I said "I hope everybody doesn't think I'm going to make this movie over and over again, because I'm not." It's one kind of movie I like, but it's not what I want to do with the rest of my career. I was very consciously trying a lot of different things. That movie brought me the opportunity to try a lot of different things, in a way that young filmmakers can't today. I made five different movies that nobody went to see. That was an important part of my development. You don't get that many chances anymore, even on a small scale. Some of the worst of them were the most important, because I learned the most from them, and the fact that they didn't work. That was a necessary period for me to figure out what kind of filmmaker I was. That was when I figured out I"m not a writer. I had to go through that to get through the other side so this other phase could start. It was frustrating at times, I was frustrated with myself.

After The Underneath, there was a similar "tear myself down and start over again" feeling, that I followed. This one is bigger. That was just about the way I was working, and the fact that it was resulting in me being the kind of filmmaker I didn't start being. This is everything. Everything has to change. This is one of those things that comes up every once in a while in your life, when you're like "I've got to tear it down."

What's the most important tool you got from those five years?

It was speed. I learned that I work better when I'm working faster. One of my Achilles heels is when I'm giving too much time to think about something, it gets worse, not better.

Have you ever been in a fight?

Not since grade school. I used to get in a lot of fights. It was kind of the way all kids fight, it dissipated into chaos pretty quickly. I went through this period in like third and fourth grade, where I was getting into fights or willing to get into fights, and then it passed. I don't know what that was about, I really don't. it's like when I was 12 I went through six-months shoplifting phase. I stole everything.

Did you ever get caught?

No.

What's your favorite thing you stole?

I stole a lot of books. It wasn't like my friends were doing it, it wasn't a peer pressure thing, I was alone. Nobody knew. I wasn't sharing this with anyone. I just went through this six months in Virginia of stealing. I was in a department store when the power went out-- this was 1975, before all the technology-- I walked out there 30 pounds heavier than when I walked in. I stole a tennis racket. In the woods walking home, I just got rid of it all. It wasn't shit I needed.

Do you think something about this 12-year-old boy has stayed with you?

I don't know. Certainly , if you're somebody who does what I do for a living, the question "I wonder what that feels like" comes up a lot. It's part of your job. I guess it just depends where your fears are, what your lines are. I wouldn't jump out of an airplane. I wonder what that feels like, but I don't wonder enough to want to jump out of an airplane.

Is there anything in particular you learned through your work with Spalding Gray?

What was confirmed by Spalding, and is something you should always remember, is two things. One is the discipline. How hard it is to be good at something. It require relentless effort. If you slack off at all, it will figure that out and it will destroy you, the piece. And that combined with his ability to make something that I knew from seeing the other side of it was really difficult, look easy. He never burdened the audience with the difficulty of the process. I'm glad people think the Ocean's movies look like I just tossed them off. I'm glad it feels that way, because I didn't.

When Contagion came out last fall, it seemed like a a model of a low-cost studio movie that people like and actually makes money. Why does nobody make those kinds of movies anymore?

Because the data will tell you that's the dead zone. $25 to $75 million is the dead zone, in terms of profitability. [But] they're movies, not cereal. You have to look at each movie and think about, "OK, why didn't that work." The audience isn't sitting around going "There's no way I'm seeing a movie that costs between 25 and 75 million dollars." That's not how they make the decision. And to their credit, Warners felt like this movie [Contagion] at this scale is manageable. They won't make a lot of money on it, but I don't think they'll lose money on it.

And Haywire is similarly kind of mid range.

When it costs $30 million to release a movie… this is the problem now, this is the one thing I've been trying to convince everyone who releases movies to analyze more. Why is this costing so much? What did you get between $23 and $30 million on this spend? Can you tell me what this last $7 million got you, and they can't. This is broken. You can't just carpetbomb TV and feel like that's going to do it.

Do you have a lot of input into your posters?

It depends on the movie. The last few years, it's such a lost art, and it's such a frustrating process now trying to get an interesting poster through, because they test everything. We've been pretty lucky. Neil did The Informant for us, and he did the Spalding Gray movie for me. We had real trouble on Contagion, all of us-- him, Warner Bros. I tend to like posters without a bunch of faces on them. We had real trouble, we spent months trying to come up with a single image that felt like the movie. We have this one that was kind of beautiful, it was like a white poster and it just had a fingerprint in the middle of it. It was beautiful, but it wasn't exciting. We kind of ended up with something that was, I don't know, something that was kind of a combination of a couple of different ideas. It was frustrating.

What about your trailers?

All the time, but unless you're going to sit down and cut something yourself, it's just impossible to get something distinctive out of that process. Again, everything's about testing. They test everything.

Do you like testing?

I don't mind testing movies. The point is, what is that for. I want to know two things. I want to know how they feel about the pacing of the film, and I want to know if they're confused. When you start getting into discussions about numbers, if you're a filmmaker who does not have contractual control over the content of the film, those can be very ugly conversations. It becomes a hammer. You can feel like a real idiot when someone's got a huge stack of paper, and they're going "Don't you see, they don't like so and so! There's 400 people, they don't like him!" And you're going, "They're not supposed to like him!" There was a lot of discussion about Jude Law's character in Contagion, which is a movie that did not score well, but I had a feeling was going to be fine. And Warners never hammered me on that shit. The one thing that came up in the discussions was, "People don't know how to feel about Jude." And I said "Yeah, I know." There's a difference between ambiguity, which is there's two possibilities, he's a good guy or a bad guy, and confusion, which is "I don't know what the hell is going on." Look, he's an ambitious character. He's a polarizing character.

Did you have any doubt about the testing of Haywire?

Oh, it tested terribly, because it's non-linear. Non-linear movies test terribly, always. You have to understand what the dynamic of a preview is. People in the audience feel like they're being tested. When you do a nothing that isn't sort of down the middle, your scores start to go down. That happened on Out of Sight, same kind of scores as this. I remember going to the test of Out of Sight, and before the [test screening manager] even got started, somebody raised their hand and said "I just want to say, I hate stories that are told this way." And it got worse from there. This guy opened the floodgates, and they just trashed it. That might be the least flawed movie I've made, and they just hated it.

You've got to be smart about what you use it for. The industry is littered with films that have scored in the 90s that tanked, movies that are classics that scored terribly. I've seen this happen, a movie will get a middling score, a 72 or something, and people feel like-- "72, I bet we can move it." I saw this happen on a movie, it wasn't mine but I was working at a post facility where this was happening next door to me. They did radical stuff to this movie, reshoots, rescore-- 72. They did another round of crazy re-editing, another score, reshoots-- 72. It was clear, this movie's a 72. And I've realized that I've never had the experience of doing two tests where the scores went crazy up or down. Maybe it's the kind of films we make, there's something in their DNA that's never going to be changed, no matter how you mess around.

What about all the talk of your retirement? You're coming out with new movies, but there's rumors...

My out date is still the same.

In some interviews you say you're going on a sabbatical, and in some you say you're retiring.

I need to tear down my process and start over again if I'm going to come back. I'm not going to come back unless I've figured out a new way to do this, by my definition. I don't know if that's going to happen or not.

What will be the point that you do go away?

A year from now I'll be done.

So what will you be doing then?

I don't know. I'll be here in New York. I've got ideas for things that aren't movies, whether painting or photography or books.

Won't you miss making movies?

No. I'll miss two things. There's a specific kind of camaraderie around the core shooting team, a kind of language and inside jokes and running gags that make no sense to anyone who's not in that group. I'll miss that. And I'll miss editing, but I can still do that on my own. i can still edit stuff just to edit it.

What about the theory that directors never make great movies at the end of their careers?

It's rare that filmmakers make their great films late. It's not unheard of-- Bunuel, John Huston. It's certainly something I don't want to have happen to me. I don't want people to say, "Wow, the last group of films weren't very good." The primary reason I've talked about it before is just feeling frustrated at my knowledge being at a standstill. I feel like there's another kind of movie out there, and I've just got to see if I can figure out what it is.

If you were a gambler in Danny Ocean's crew, would you bet on your own retirement?

You should put money on it. Don't bet against me.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend