A lot of people say, “I love you,” in Ira Sachs’ Married Life, and despite the odd circumstances, no one seems to be lying. That’s a pretty impressive idea for a movie to deliver when it is at the same time doing its best to convince us that none of the characters is in love. Then again, maybe I should have said that no one seems to be lying… to the other person. Married Life centers itself around Harry Allen, a businessman in the late 1940s, filled almost to bursting with the eras face-front propriety. He is also cheating on his wife, Pat, and planning to leave her. The film opens with Harry confessing this to his best friend Richard. Richard is something of a playboy, but the '40s version. He fits in at the businessman’s cocktail lunch just as well as Harry, but he has a more progressive conscience, and his cigarette hangs from his lip at a jaunty angle.

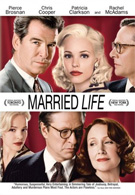

As Harry unburdens himself to Richard, he introduces his mistress Kay. Harry is so far along in his visions of the future, and the life of true love that will follow, that he is already intent on laying the foundations of friendship between his best friend and future wife. Kay is the poster girl for the near-50s, with hair that is a blonde not found in nature, and skin that makes you wonder how every frame of a movie can be airbrushed. Obviously, Richard instantly decides that he must have her for his own.

The real play begins when Harry finds himself pressed beyond what he can stand between a rock and a hard place. The truth is, there is little that’s especially wrong with his marriage. There just isn’t any passion in it. His wife freely admits that she just isn’t the sort that shows affection, outside actually having sex, and the two of them basically live as something like partners in what is just an unusual kind of business entity. The wrench in the whole thing is that they actually do love each other immensely. It is perhaps in a sense more akin to loving a sibling, or best friend, but they wouldn’t hurt each other for anything. Harry’s dilemma then is that he just can’t leave his wife. He can’t do it to her. In the grand tradition of love, helpfulness, and good intention gone horribly wrong, he decides that he’ll have to kill her, and save her from the life of misery and unhappiness that would follow if he left her.

On the surface, Married Life is about just that, and the idea that we can never really be sure what’s going on in the other person’s mind. It is about that, I suppose. It plays out that way, with the audience watching the scene, knowing all angles as we do. We see the characters stumbling through the unreality of their lives, trying to decide how they are meant to react to situations. They are characters playing characters they create for themselves. One brilliant scene finds Richard almost jumping out of his skin trying to work out the rules of decorum as applied to a highly uncomfortable revelation.

But, this is a story that tears down appearances at every turn. The lies we tell others, and our inability to be certain that our partners, or best friends, aren’t going to stab us in the back is all just the stage - the stage we are born on. The play is really about the lies we tell ourselves. Murder as benevolent act is stretching the metaphor a bit, but it is only one of the film’s topics. In the end, odd as it might sound, it is a small part of Married Life’s discussion. It is ultimately only the trivially unique feature that paves the way for telling this story that is, of course, about everyone.

For those familiar with Douglas Sirk, or those who enjoyed the recent Far From Heaven, Married Life is going to be a comfortable experience. The facade of picket fences and neatly trimmed hedges as life is lifted directly from his period-critiquing melodramas. Ira Sachs takes it a bit further down the road here, mainly in that Harry and Pat seem not only locked into their roles by propriety, but are also somehow addicted to them. They don’t really know who they are beyond the personas they have lived for so long, and it can be difficult to distinguish killing the only “you” you know from any less metaphoric suicide.

The lesson, and I’ll presume to know, is that Harry and Pat aren’t quite people. They are what happens when attempts at civilizing go too far, and that conflicts with nature - a collection of moral principles they are taught to be, rather than uphold. The result cannot cope with the idea that anything might be wrong; that the system might have broken down somewhere. Richard, played to perfection by Pierce Brosnan, is not someone you want writing ethical guidelines himself, but he is human. Surrounded by those who will follow their choices into misery, simply because to have been wrong is admitting something inconceivable, he is asked if he regrets anything. “A lot,” he answers, “and much more to come.” The DVD does not come with a great quantity of special features, but what it has serves well to anyone who enjoys this film. There are, somewhat amazingly, three different alternate endings included. They are all similar, and all a significant divergence from the actual ending. This is just the sort of movie where this inclusion is apt to be most appreciated, because the thoughts of the director as storyteller are especially relevant. Any of them would have ruined the overall product, but it is fascinating to see where the story almost went, and to get some insight into the overall process.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

The only other special feature (apart from the original trailer) is a commentary track by Director and co-writer Ira Sachs, and its one of the best such commentaries you’re going to find. Sachs is not a big name, and he isn’t likely to ever become one. On the other hand, he’s only made six movies, and already has two Grand Jury Prizes from Sundance. He’s also clearly a very serious student of what he’s doing, and riding along with him through Married Life is not to be missed by anyone with anything like a positive reaction to the film.

I’m not generally a fan of commentary tracks. I find that after about twenty minutes there isn’t much left to say, and the humorous production anecdotes run dry. But, if you’ve experienced something like Roger Ebert’s commentary on Dark City, you have an idea of what a good commentary can deliver, and Sachs delivers a similarly enlightening experience. He does wander off occasionally, but for the most part true fans of the theory of commentary will be impressed. He lets in on why decisions were made, and why he thinks they work. How scenes were put together, why they were shot in this way, and what the result is supposed to be doing. He even lets us in on some things that maybe didn’t work out in the end as they might have. Well, he’s got four endings to the thing, I suppose some things didn’t work out.

Married People is a movie with a lot to say, and he’s got a lot to say about it. It also delivers, as I think any really good commentary track should, in ways that are not necessarily specific to the movie under review. It reveals a lot of what moviemaking is, and how it can be made to work. The only thing disappointing about the DVD, which really is a great package, is that some deleted scenes, or even some production notes about alternate scenes, would have pushed things just that much more.