Scott Cooper’s Antlers is a movie with a good head on its metaphorical shoulders, and a healthy appreciation of the greatness that exists in horror filmmaking. It’s not overly invested in cheap scares, earning its bigger moments with atmosphere instead of quick reveals and score crescendos, and it’s smart enough to unlock the allegorical power of the storytelling style by rooting itself in real world monstrosity. It has engaging characters, brought to life by a talented cast, and when appropriate, it has a willingness to really let it rip with shocking gore and violence.

For all of these reasons, it’s a feature that genre fans are going to want to love – but unfortunately it’s an experience that isn’t totally able to hold together before the end credits roll. While the movie has a number of good ideas, it isn’t able to totally take advantage of them with proper coalescence by the third act, leaving you with a pervasive feeling of wishing that there was more to it. There’s still plenty to like, but it falls short of meeting its full potential.

Based on a script by Henry Chaisson, Nick Antosca and Scott Cooper, Antlers balances its Oregon-set story between two protagonists: a small, bullied 12-year-old boy named Lucas (Jeremy T. Thomas); and his elementary school teacher, Julia (Keri Russell), who has recently returned to her hometown after years away and is temporarily living with her brother/the local sheriff, Paul (Jesse Plemons).

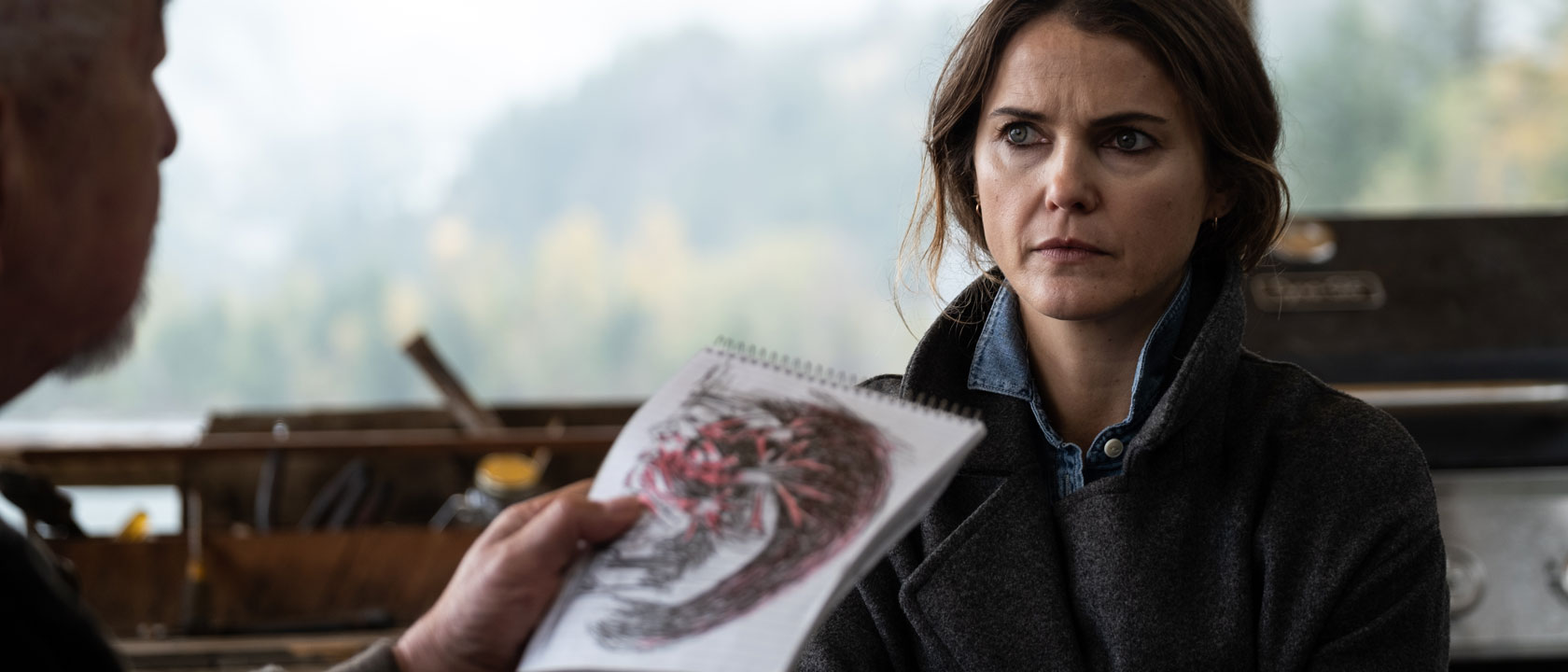

Having personally experienced abuse at the hands of her father when she was her students’ age, Julia takes a special interest in Lucas, and believes that he may be having serious troubles at home – her suspicions only growing greater as she discovers sincerely disturbing artwork in his desk, and learns that the child’s dad (Scott Haze) is a single parent with a criminal record. From an outsider’s perspective, all of the red flags are waving, and it has every appearance of being a terribly typical case.

These suspicions are warranted, but the case is anything but typical. As we follow Lucas home, we learn that he’s living a life of struggling self-sufficiency – his house a dark mess and each meal is catch-as-catch-can with no money and resources. But he’s not alone. Behind a heavily locked door is a mysterious, feral being that Lucas cares for by providing it animal carcasses that he finds on his way coming back from school. The boy hopes he can care for it and continue living his life, but horrors await as the secret is uncovered and the truth of the circumstance is revealed.

Antlers tries to use horror to say something about abuse, but the metaphor doesn’t totally track.

Above all else, the easiest thing to appreciate about Antlers is its allegorical intent and attempt at being more than just a cool monster movie. Some of the best examples in the genre root themselves in the terrors of non-supernatural reality, lending the material deeper resonance and verisimilitude, and there is an earnest attempt made by Scott Cooper to establish a link between the film’s fiend and the trauma of child abuse. The problem is that while this work stands up through the first two acts, it withers away in the third and leaves the experience feeling unsatisfying – with one’s initial admiration of the setup dissipating in light of the lacking resolution.

This is tricky material to discuss in what is intended as a spoiler-free review, but too significant not to acknowledge. Analyzing the beginning and middle of the film, one can draw one-to-one lines between real world horrors and the movie’s fantastical interpretations – especially because of the unfolding story about Julia’s experiences – but those connections fall away as Antlers ascends towards its climax, and really disappear altogether in the final moments in aim of including some form of “twist.”

The story in Antlers leans towards messy when the monster is unleashed… and not in a good way.

It’s not just the cracking metaphor that hurts the third act of Antlers, though; there is a point where the script seems to be unsure of how to proceed forward beyond just barreling towards a final confrontation. After spending an hour or so establishing characters and dynamics, and slowly ladling exposition that allows audiences to put pieces together, it just goes into plot mode and starts putting everything out on the table. You no longer have to question how Lucas ended up in his position, as there is a series of blunt flashbacks that spell everything out. And you no longer wonder about the supernatural side of the story, as Julie and Paul are able to get a full, no-doubts lowdown on the situation from the town’s Native American former sheriff (played by Graham Greene), who spells out the mythology for them.

The movie gives the impression that at some point in pre-production the writers were told to cut 20 minutes out of the script, forcing a lot of material to be condensed, and it’s ultimately very much to the final product’s detriment.

There is a great monster featured in Antlers, and it is savage.

Antlers may lose what makes it most interesting in its third act, but what it is supplemented is some solid straight monster-driven horror, and that material certainly is effective for what it is. Scott Cooper’s dark, somber aesthetic throughout the film effectively lends it a haunting, creepy atmosphere that sets the stage for all kinds of bloody mayhem, and he doesn’t pull punches when it comes time to shred human beings apart into jagged chunks of muscle and bone. For being Cooper’s first intentioned step into horror, the movie effectively demonstrates the director’s impressive genre instincts, and suggests it’s a world and tone in which he should continue to play around in the future.

Given its promise and everything it does right, Antlers winds up being a frustrating experience. It’s always exciting to see horror taken seriously and constructed with detailed purpose, but the movie’s aim falters at exactly the wrong time, and the issues badly undermine the best aspects. There is plenty to appreciate in its crafting, as it looks terrific, has bold style, and features quality performances, but it’s let down by its disappointing conclusion.

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.