Brave Director Mark Andrews Talks Haggis, Killing Babies, And Taking Over Someone Else's Film

If you spend 5 minutes at the Pixar campus in Emeryville, California, you're bound to hear someone talk about the brain trust. Every person in that building, which is painstakingly designed to feel like a wide-open and welcoming college campus center, will credit the "brain trust" with Pixar's unparalleled winning streak, thirteen hit films and many more to come. But as intimidating as it sounds, the brain trust isn't some giant bank of computers spitting out ideas, or some central command center where an animatronic Buzz Lightyear barks orders; the brain trust is a group of men and women, sometimes wearing goofy Hawaiian shorts or rock-star long hair, who tear apart every Pixar movie over and over again until they get it right.

And Brave, their newest film set for release on June 22, went through that process of death and rebirth more than most of the studio's films. It's been in development for six years, and two years ago, with the release date deadline looming, director Brenda Chapman was replaced with Mark Andrews, a brain truster himself who'd just finished work as a co-writer on John Carter of Mars. There were bits of concept art and models for Brave sprinkled all over the campus when I visited in March-- some of it intentionally set up for visiting press, some of it part of the rotating decor-- and plenty of it spoke to sequences and scenes that are no longer in the film. We saw a "color script," in which entire scenes are represented by very impressionistic splashes of colored paint, and it included an entire snowy opening sequence; as producer Katherine Sarafian admitted, the snow was a hard loss, but "as the story developed, we found that we didn't need snow in all these scenes, we needed all the various weather patterns that develop in Scotland." So out went the snow, in came rainy moors, and in came months and years of more work.

The day I spent at Pixar ranged from the frivolous-- archery and bagpipe lessons out on the lawn! buying stuffed animals at the gift shop!-- to the truly fascinating, talking not just to Andrews and Sarafian, but the technical geniuses behind the kind of intricate details that you never notice but make Pixar films utterly unique. Take our heroine Merida, for example, whose trademark is a head full of fiery, crazy curly red hair. The Pixar team had to invent new technology to create that hair, and as simulation supervisor Claudia Chung told us, it took 3 years to get it right, including bringing in curly-haired models and simulating the growth of every single curl off her head. If you take a close look at the teaser trailer for Brave, her hair looks different than in the final film, since the technology was still developing when they made it.

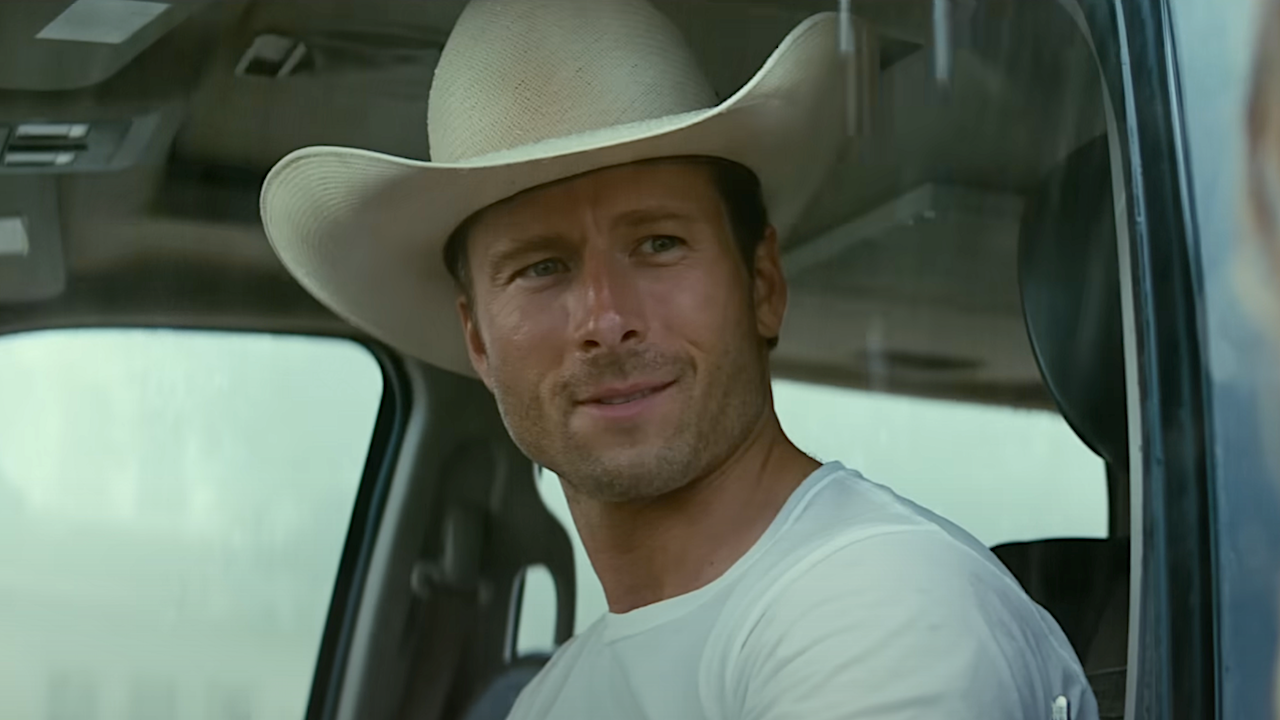

The amount of detail that goes into making a Pixar film is overwhelming for more ordinary humans, but for one man, it's just been part of the last two years of work. To start off our week of coverage and interviews for Brave, here are the highlights from my two separate conversations with director Mark Andrews, who is the film's co-director along with Brenda Chapman. I asked him about the challenges of taking over a film midstream, of telling a story about a teenage girl and her relationship with her mother, of "killing babies" by cutting out stories and characters his colleagues were attached to, and of working at a company where the only storytelling rule is that there are no rules. He also let us know about the secret to nailing Ratatouille's story, and also a very valuable secret about where not to eat haggis when you're in Scotland. Read all about it below!

Halfway through the footage they showed us I realized this is a mother-daughter story. Is that the emotional heart of this movie?

You say mother-daughter story, no guys are gonna go, because [yells] "Where are the dad and son stories??" For me, it's deeper than that. It's a parent child story, it's that universal relationship. I'm a dad myself, I have a girl and then boy-boy-boy, kind of like King Fergus. It kind of mirrors up. I know what I'm going to be going through when she becomes a teenager.

And then for Merida, being a girl and me being a guy, it doesn't make any difference, because she's a teenager, and all teenagers have that universal teetering on adulthood. They don't know who they are. There's what they were as a child, and having to decide who they're going to be when they're adult, and not being ready to go into it. There's a real Peter Pan/Wendy quality to her, exploded out from as simple as that story is. It's kind of those simple truths that have that universal appeal and relatability that I gotta focus in on.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

I talked to my wife--she's the youngest of 10 and has 7 sisters, one of her sisters is a psychologist, she has teenage daughters, so I talked to her about being a mom of teenage daughters. I talked to the teens about their mom, talked to her about being a teenager herself with her mother, so I got a lot of insights. Those kinds of specifics are just some spice. At the real core is this relationship that could be daughter-son, father-daughter, father-son.

There's the classic Disney princess story of the girl who wants to run away from the castle, but you guys are clearly going beyond that. Do you keep that archetype in your rearview mirror and get away from it, do you build on it and make it deeper?

The archetype is only on the surface. You start there, but you find out it's so much more rich. We've never seen any of the princesses as children. And why do they always want to leave? In this, we have none of that. We start there and do an abrupt about face and go the other way, so you're going "Whoah whoah whoah, I've never seen this type of thing before." We go down some of the same paths, but quickly go off. It's a personal story. The conflicts that are happening in the story are all within Merida as she's crossing that line from childhood to adulthood, deciding who she is and what her decisions are actually going to mean, and her mother trying to do the best she can to help her with that.

When you came on as a director, were you on a different project or had you been involved in this somewhere since the beginning?

I had just finished John Carter of Mars, I had just come back from doing principal photography. Then I went into development here, and then it was at the end of that summer that Pixar asked me to jump on board to help out, at the end of the summer of '10.

So they did all these fact finding trips to Scotland years ago with the art department, and you were nowhere around then?

Well when Brenda first pitched this, and she was in development, I would walk by [her office] and see girls holding broad swords and guys in kilts, and I would poke my head in and say "What's going on here, this is all the stuff I like, what are you working on?" And she told me the story. So I became her de facto, on the fringe, all things Scottish and medieval consultant. I've been part of the project on the fringe, as kind of a satellite go-to person, since the beginning. I went with them on their first Scottish research trip. John said "You go! They need you!" Their trip was designed off the trip I took with my wife on my honeymoon for a month, going around the Highlands.

This is such a personal story for Brenda Chapman, so how did it become a personal thing for you when you took over?

When I first got on to the project, I come on with this objectivity, which is exactly what it needed. It was stuck n the story gunk, stalling out, not progressing. I can come in with an objective eye and go "I don't care, chop chop! This doesn't work, this doesn't work" and shatter it and go "OK, what still works?" Take Brenda's great idea, take this great characters and those relationships that she started, clear away a lot of the clutter, find out the missing places, go in there and solve them. I didn't succeed right off the bat. No, story is hard. It's the hardest thing there is to do. We twist and contort with pain and agony in story. John does, Andrew does-- they have Academy Awards, but every time it's the same thing. They need help too.

There was a lot of baggage that came with this because it was in production for a while. When Brenda first started, they had a long time to do it. That it went that long and kept going-- and there were a lot of other things working against it being a quick release. They were developing the new software system, rebooting all that stuff at the same time in tandem, so we could actually make this movie. None of that stuff existed, we couldn't do it the way we did it on the old software. There was a lot of slow bumping around, that was fine. But you get to almost two years before the movie is out, and it's not there yet. There is the business side of it too, that we have to make that deadline, and something's gotta change. And we've done that here at Pixar a few times, director changes, or writer changes, or holding it off months for its release to give it more time, or canning something completely in development. And it happens in Hollywood all the time.

What was the specific direction you were trying to take things?

It was getting everything to work and flow throughout. There were issues that we were telling mom's story and Merida's story and dad's story, and we needed to whittle it down to Merida's story, she's the main character. It isn't a power play between Merida being more like her dad or more like a mom and vying for her to be one or the other. There were a lot of things happening in the story, and I wanted to come in, and to get it to work is whittle out all the stuff and find the clean throughline, which is a lot harder than it seems. I've been doing stories for 20 years, and Pixar has great films, but it's never easy. John, Andrew, you go into a story again, whatever experiences you had on the first story you did, whatever you think you solved, don't apply it to the next story, ever. We did it on Ratatouille, there was a lot of extra clutter that me and Brad just went through and went "Zip!" "What if there is no rat family? Done! What if there is no Gusteau? Done!" And whittled it down to Remy's story. Now what else do we need to put back?

So you whittled it down to Merida.

I whittled it down. I approached it like we approached John Carter. Here's this adaptation of this book, here's a story, there are great themes in here, great characters, but there's too much, and a lot of this stuff doesn't work. So we clear that out, and now what do we have left? We've got some big holes, and we've got to fill them. That was my approach on this, and being able to be objective when I came on just kind of helped, that I could kill some babies that everybody was holding on to.

That seems like it has to happen all the time, and everyone acts so rational about it. As a director to be the guy who kills the babies, how do you get used to it?

I don't think you ever do. I think it's a discipline that you realize that's always going to be in the back of your head. You have to love something fully and completely to put the time in to make it work. To realize that's not working, now I have to put on a different hat to kill it, so I can get it to work for the betterment of the greater scheme-- that's alway hard. It takes samurai discipline to do that.

Brave seems darker and more serious than your typical Pixar film. Can you talk about the decision to go in that direction?

Y'know, on Incredibles, we open up with bad guys shooting at cops with machine guns. We kill cars in Cars 2. An old lady dies in Up. I don't know "typical." Maybe if you compared it to Toy Story or A Bug's Life. The cool thing about Pixar is everyone is trying to put us in a box, and our box is that there is no box. What typically makes a Pixar movie is that you're in the hands of really fantastic storytellers who are going to give you a great movie. You're not going to know what to expect anymore, these days, because we can do anything. We embrace the darkness. We love that. And finding that right tone of darkness.

So have you had haggis?

Yes I have, several times, it's great. Just stay away from the roadside haggis. You don't want the McDonald's haggis.

Is that a rural Scotland thing?

No, it's just cheap. To do Scottish right is expensive.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend