Cowboys & Aliens Set Visit Interview: Director Jon Favreau

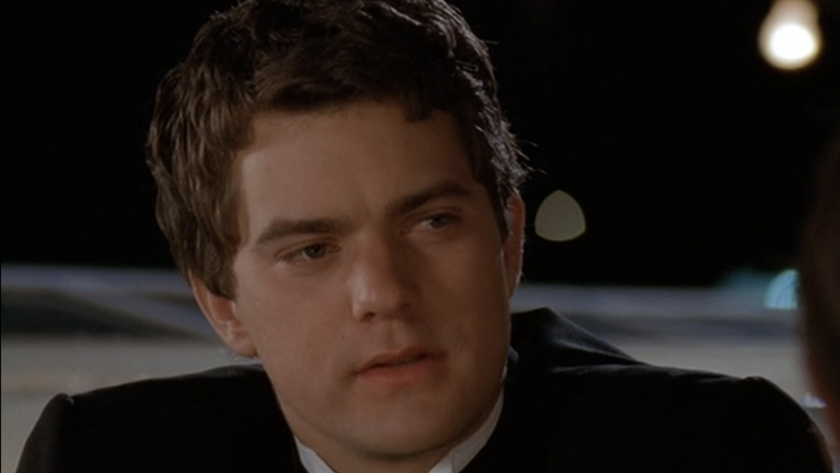

Jon Favreau has always been a solid director, though it wasn’t until recently that he has begun really getting credit for it. Since 1991, he has made films such as Made, Elf and Zathura, but it wasn’t until he helmed the incredibly successful Iron Man in 2008 that he established himself as blockbuster director. Now, for the first time, he’s taking that newfound success out of the Marvel universe and bringing it to the old west.

This past August I had the incredible fortune to travel to Santa Fe, New Mexico to visit the set of the upcoming sci-fi/western mash-up Cowboys & Aliens, starring Daniel Craig, Harrison Ford, Sam Rockwell, Olivia Wilde and Paul Dano. With camp set up in the beautiful Plaza Blanca, Favreau was gracious enough to sit down with us for an extended amount of time and discuss all of the in-and-outs of the production, from what it’s like working with filmmakers like Steven Spielberg and Ron Howard; how they’ve worked to established the tone of the film, and what it’s like working with such a stellar cast. Check out the interview below.

Is the look of the alien ships kind of a call back like the ancient astronauts, you know, like the cave drawings?

Yeah, we tried to look at – you know, there was that first photograph of a spaceship was from I think the 1870’s, not far from here – early Sam Rockwell, right [laughs]. And you know, they had the first shot of a UFO was like a cigar-shaped silver thing in the air. And there have been certain recurring themes and sightings and – and then the way film has treated them, UFOs. So we tried to use - reference stuff and make it fit into the cultural memory of alien stuff, especially – you know, I’m more of a fan of the alien movies from – you know, I guess I grew up around the time of Close Encounters, E.T. And then Alien I like a lot, and Predator. So we’re definitely going for more of the horror side of the alien movies – and although we have quite a bit of CG – I like the way they told stories before – before you could show everything with CG. And it was a real unveiling of the creature, little by little, and using lighting and camera work and music to make it a very subjective experience.

And so we tried to preserve that here, even though we have ILM and we could show everything from the beginning, it’s nice to let things unfold, in a way – especially because you’re seeing through the eyes of these people in this western milieu. And then for the western, we really tried to embrace that and not try to update it too much or change it or make it more accessible for a younger audience. We figured that the alien side of things hopefully will take care of the people who don’t know the western, but for people who love westerns, let’s do it using all the archetypes of the classic western films. So we’re really trying to do something, you know, we’re really trying to do something classic here, and that feels like it could have been made at an earlier time, except for the technology with which we can show like effects, which is nicer that – be dealing with this, rather than just motion control, lighting rates and things.

But, again, using as much practical as we possibly can, then using CGI to help make it look not so modern. So we have Legacy doing a lot of the alien work with us and ILM working hand in hand with them. And as you can see, we’re sort of shooting – you know, these backgrounds here are things that a lot of movies would just shoot it in a convenient place and put that in. We really found these wonderful unique locations. And then as you’ll see later – maybe we’ll walk you guys around – is the base of one of the alien craft there and you’ll see that that’s what we’re building off of, so we have practical things that people can interact with. And we’re building some sets at Universal, as well.

Yeah. From a western side of it – is it like a 60’s, 70’s western? Because you know, I think Daniel Craig – I’m thinking Steve McQueen and the Magnificent Seven –

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Yeah. He looks – he looks remarkably like, you know, Steve McQueen did in the 70’s. It’s interesting, because you think of him as James Bond, but the minute you put him in – you’ll see him in his whole kit, as he calls it – his whole outfit – and he feels really – you know, like the type of actor that you could cast back in the 60’s or 70’s. And we looked at films like The Professionals, Magnificent Seven. But the first meeting I had, along with Bob Orci and Alex Kurtzman and Damon Lindelof and with Steven [Spielberg] – he screened The Searchers for us. So I definitely watched and went through the whole John Ford, you know, all the John Ford films I could get my hands on. And also some [Sergio] Leoni.

But they all – each era did their version of a very similar structured story type, so we tried to preserve those archetypes in those characters, and figured it’s time for our generation to take that class historian, and show it through our perspective. And there was a big gap, because I don’t think people accepted the western the same way that they had pre-Vietnam, just because it felt a little insensitive, racially, at times, in who the bad guys are and what they represent. And as archetypes, it all worked very well, but as people became more socially conscious, it didn’t – some people found it distasteful until you lost a whole tradition of the western because it became – it felt anachronistic. And then action movies took over, or cop movies or vigilante movies, or sci-fi, would take those archetypes and stick them in space. Now we kind of go back to the old western and because now you have a bad guy that are aliens, it’s not racially divisive anymore. And actually we have – the story’s about the Apaches and the cowboys being forced to deal with one another.

So we tried to start it off with this – as real as we could historically, and as real as we could, in the context of the western, the traditional western film. And it’s interesting to see how these characters are forced to interact with one another based on this looming threat. It was an expression during the Cold War that said the only way Russia and the United States were going to get along and make peace is if a spaceship came and attacked the Earth. You know – a common enemy is – it’s interesting to examine all those characters in a strained situation, and try to play that out as real as we can.

Are the aliens fairly biological?

There’s, you know, there’s – yeah, they are. It’s not like a 50’s, you know, walking robot anyways [laughs]. It’s more in the tradition of like Alien and Predator. You know, that’s what’s compelling. And then that allows for – you know, you could create the biology of the alien that feels the most horrifying and feel it slowly over the course of the film, as opposed to just form these columns of aliens marching out from iris valves and that sort of thing. You know, it’s not Mars Attacks.

Was it a challenge finding a unique design, something that hadn’t been done before?

Yeah, it’s very hard. You know, but thank – you know, actually Steven Spielberg was very involved at that point. And it’s hard to have a brainstorming session with Steven Spielberg because he’ll start talking about, “Well, in E.T. I did this, and then in…” You know. And then you’re just – it’s hard for you to – it’s hard to not be distracted by that, you know. [laughs] You know, because you’re hoping those stories will come up when you sign on to work with these people, and between Ron Howard and Steven Spielberg and Harrison Ford, you know, half of what’s fun about this project is just getting to know these people and be colleagues with them, and getting to either get their advice because they’ve done so many of these films. You know, talking about an action sequence, the way you break something down with Harrison Ford. I mean, he’s – you know, between Indiana Jones and Star Wars and the Jack Ryan series and – you know, he really has a real deep understanding of filmmaking and how to make action scenes work.

You know, usually the actors I work with are really tuned into dialogue and character, but he really understands the whole overall of it. So I’ve learned a lot from him and of course, Spielberg and Ron Howard. You know – just the – talking about film theory or storytelling, or what would be exciting; and then hearing stories about what they’ve tried and how they did it. And me being able to pick their brain about, “How did you do it, either back then, or what’s worth exploring now?” And then sharing the resources of people that they’ve worked with. It’s just been – at this point in my career, it’s really a welcome new layer to add, to be able to actually have people that I can ask questions of and who know so much about making movies.

Can you talk a little more about just the casting? Some of the actors bring a sort of iconic weight really to the whole thing. I’ll just say Harrison Ford caught the public eye as a space gunfighter, now And then even Keith Carradine – I mean, Long Riders, Wyatt Earp…

I mean, every – I mean, even our supporting cast – Walt Goggins, you know. And Julio with The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada. I mean, all these people are stars in their own right. And for this ensemble to be this full with really good actors – and then to have iconic actors. And that’s very in the tradition of the western, as well. When you cast John Wayne, you were getting – everybody who sat down was like, “Okay, what’s John Wayne gonna do in this movie?” And when you cast Harrison Ford, he’s bringing all of those – that whole tradition of sci-fi and action, and even in – he’s always playing a version of a cowboy, even though he’s only played one once in his career on film –

Frisco Kid.

Frisco Kid – But you think of him as a cowboy and he really, you know, he’s an excellent rider, good with – you know, he understands the weapons, he understands the culture, and the rules. See, I don’t have all that dialogue. I usually have a fire hose of dialogue to use, whether it’s Elf or Swingers or Iron Man, certainly with Downey – the dialogue could always, I could always root around through the scene and discover it. But with here, it’s very simple – a lot of scenes are like one or two, three lines, and a lot of it’s just looks or gunfights and things like that. It all has to make sense with western logic, and it’s a whole new set of rules that our generation really didn’t grow up with like earlier filmmakers, where you were watching it every day and you just understood it. So it’s really like learning an old language.

The only westerns I’ve seen have been revisionist westerns, certainly recently, except for, you know, like Unforgiven or – the rare exception – it’s usually a sensationalized version of the western or a new twist on the western or a western with an interesting piece of casting that breaks the rules of the western. But all the way back from like – what was it, Back to the Future III – it just becomes like a fun backdrop as opposed to, you know, you’re buying into the whole tradition of it – and how are you going to – it’s like a song that you’re covering. You know it’s like each musician would cover, you know, “Bye Bye Blackbird” and it would be done differently by Billie Holliday than it would by, you know, Louis Armstrong. And it tells you about that moment in time in music. And the western used to be that. It used to be the same story – Jessie James, cleaning up the town, you know, cleaning up Dodge City. Every generation did its version of that – Billy the Kid, you know. And each new set of actors, it would reflect that era. And so it’s fun now, having had nobody really do that, to try to explore that now. As a filmmaker, it’s a bit of a luxury.

Does it feel like you’re kind of directing two movies, in the fact that you have – you’re juggling the sci-fi with the western? Is that sort of like a challenge?

It is. There’s a lot of overlap, and that’s what we really wanted to explore. We didn’t want it to feel like a skit. You know. And so the overlap is with our casting. Our actors work, would work for either genre. There’s a sense of – there’s a very – what’s happening on the outside usually reflects a lot of what’s going on internally with the characters, in the classic sci-fi. You know, Close Encounters was about a guy who was somehow estranged from his family, and if you remove the alien element, you could still make a drama based about Richard Dreyfuss and him coming apart, and that could have been another woman or his career. But sci-fi filled that hole. The same thing with E.T. About divorce and about abandonment, and somebody yearning for that companionship. And then this imaginary friend comes in. And that’s sci-fi.

And I would extend it to other films of that era, especially like Spielberg’s stuff –Jaws – each of these works without the element that makes it a big movie. And what’s nice about both sci-fi and the western, it usually represents some conflict that’s being brought up to a larger, you know, for the sake of the opera of making it into a movie – things are bigger than life. But it’s really dealing with very human elements – coming of age, being challenged, bringing you know, civilization, overcoming – whether it’s the savage side of yourself or taming the West. Both of the genres are usually very character-based and deal with human frailty. And both of them deal with loss a lot, and death. The gunfighter has to move on. Each small town the gunfighter move through is almost like a Purgatory. And you see it especially with movies like High Plains Drifter where moral scores are settled.

And a lot of sci-fi movies, especially alien movies, has to – that deal with abduction – are usually dealing with scarring, usually around death but could be about subconsciously bad, weird upbringings and family relations, you know – this blanket of the abduction or aliens coming, usually is shrouding some deeper anxiety or fear. And then people think they see UFOs – or that’s what those stories unfold to be. And so you’re dealing with, again, fear of moving on and death, with Richard Dreyfuss getting on the ship, – or saying goodbye to E.T., letting him go home. It’s usually dealing with mourning on some level. So there’s a heaviness to both genres that give both a bittersweet flavor. And so what we tried to do is find where those two genres overlap and explore that. And of course, I’m talking a lot about this.

But when you see the movie, you’re going to see spaceships and aliens and it’s going to be bigger than life. But for the inner fabric of the movie, to make it not just a popcorn movie, where it’s just filled out trailer moments, and giving it some thematic and – give these great actors something to really deal with, in this big ensemble – each character has an arc and each one changes over the course of the film.

So I like working on these big movies because if you get it wrong, the filmmaking, you still have all of the great, beautiful window dressing, and it probably will make its money back [laughs]. You know. So there’s that safety net that you don’t have with independent films. But if you could get that part right and then you could actually tell a story and make people feel something in a movie like Cowboys & Aliens or have some humor or humanity to it, then I think the audiences really reward you and they’ll embrace the film and it’ll become one of those movies that somehow withstands the test of time and people will check it out later, when it comes on television a few years later. And they’ll say, “I liked that movie.” You know. And I’ve had that experience a few times… but I like the idea that it’s just –Cowboys & Aliens – people are going to see – think they’re just going to see a summer romp and then they see something a little more special.

How much of a story are you giving the aliens? Do they have a purpose for being here?

They do. I mean, we have an internal logic to it. But definitely, in again, the movies that I like, it’s not like you’re going to be cutting to the bridge of the alien ship like in the “Treehouse of Horror” [episodes of The Simpsons] [laughs]. It’s more like – you can infer certain things. Again, to me once of the best examples is Alien. There was a logic to it, but the way it unfolded, you didn’t really know it. And there was enough logic to it that you could accept it. But all I knew when I watched it is, “Oh, my God, what’s that?” There’s eggs; it’s on his face, It’s coming out of his stomach, and they’re all over the place, you can’t kill them; they have acid blood. Those were things that were pulled together, saying what they were colonizing.

But I really liked the experience, and how the actors, and how Sigourney Weaver was going through it, and how much it was affecting her – the nightmares she was having. And then as you – and the more I learned about the aliens, the less I enjoyed them. Like when they were these horrific images that – these very real characters I was investing in, were reacting to – even in the second one, you know. You’ve got a sense that it meant a lot to them. And I kind of got what they were about. But I – as curious as I was, I was more curious about the moments of the actors, and how it affected them. And I would say the same thing about Predator. I guess they were coming here to – I mean, the Alien movies I liked the most, I don’t know that much about, and the ones I knew more about – it got away from horror and more into sci-fi and action. And I want to keep this more in the –

So you’re not necessarily creating a…

There is. I mean, I could – after the fact, I could walk everybody through why these actions are justified. But a lot of it’s for the impact of the way these things unfold. And certainly as you’re doing one – you know, I think as movies like that get into sequels, you start to have to reinforce the mythology. But in the first one, you can surprise people and come at them from all angles, and I think that that’s what’s fun about this; it was fun about a movie like Cloverfield. It was a logic to it, but all I knew was it wa s really cool and I was really scared, you know [laughs].

Now, this is based on a comic book that’s not that well known. As opposed to, say, Iron Man.

By me, either [laughs].

Do you feel a lot more freedom, working with the material?

Yeah, I mean, honestly I was exposed to it. I knew the title, I knew the image of a cowboy running away from a flying saucer, it’s pretty cool. And then [Mark] Fergus and [Hawk] Ostby had been attached to the film when I was writing Iron Man – and they had written Iron Man – well, when I was making Iron Man they had written Iron Man and I had heard about it, and had a meeting with Spielberg about it – I thought it sounded really cool. And then for a while, Downey had even met and was attached to it, before Sherlock 2 happened. So I heard about it again.

And then I met Kurtzman and Orci at Comic-Con last year, and just – we had a general meeting and they mentioned that that was one of their projects. And I said that’s one I’d always heard about, that Downey had been attached and Ferguson and those people attached. And they sent me the script, and it was really the script that – it was a real page turner. I was like – after Iron Man and Iron Man 2 where it evolved from outlying to just as the bell rang before we started shooting, into a shootable script – it was nice to have a piece of material before we ever started the casting or prepping, and it was a very strong script. So I don’t know that much about the comic book, but I do know, you know, we definitely reinvented things, from the images that I’ve seen.

Does this shoot feel like much more, sort of under control, in a classic way.

It’s nice to – I mean, it gives me – like, I’m very proud of the Iron Man films, and I think that we found a really good balance. But the personality of the film is affected by the personalities of the individuals. I could be very dialogue driven and very spontaneous and open to improvisation and reinvention of moments. In the first Iron Man we did that quite a bit; and the second one, even more so, as Robert Downey’s personality affected the way the rhythm of things. And there were certain things I could prepare for with Robert; certain things I just had to be prepared for anything. With this one, you know, there’s been a tremendous amount of preparation. You’ll see the camera work is a lot more decisive. You know, again, I’m working with Matthew Libatique so I think it’s the personality of the film that’s going to affect things.

And also, with Iron Man you’re shooting plates; it’s about the characters, with multiple cameras to get the spontaneous dialogue. Here, you can really make it about the locations, about the vistas. And in a western, the character is a small piece of the landscape sometimes. And sometimes, what’s going on behind their eyes. But Daniel, you know, is working off of – you know, Robert’s speaking a mile a minute, and you know, a gunslinger doesn’t say that much. He says a lot with his actions. And you have to make the actions the dialogue, whether it’s the gunfight, hand-to-hand combat – that’s all part of his personality. And in a weird way, the dialogue is almost a secondary concern. They might say one thing; they usually are under spoken. And then when the gun comes out or they start fighting, that’s when you see the real side of their personality come out. And so a lot of it has to do with preparing the stunts, dealing with the – you know, we have a lot of interaction between CGI aliens and real people on real horses. And you’ve got to get that right, otherwise it’s The Valley of Gwangi [laughs].

But you have a film with so many on-set resources and so many post production resources, in the western, which is incredibly resourced and location intensive…

And a lot of time.

Right. Do you wake up some mornings going, “What the hell did I sign up for?”

No, I love it, you know, I really – it’s hard to – when you’re traveling out to a remote location, it’s hard. Sometimes, you know – this ground is nice and level because this is a flood plain. So if it starts to – the weather here’s crazy, and if the thunderheads come in and it starts to rain, we have to evacuate. Otherwise, you know, we’ve been up to our – we’ve been sitting like this, and then we’ve been up to our knees in water.

Is this a franchise? I mean, do you guys – working towards that and setting stuff up?

I know the studio seems to be really positive on what we’re doing here; I love working with this group of people. DreamWorks have been great collaborators, and Universal’s been wonderful. And we even have Paramount on the international side, I love those guys.

Now, don’t be counting your sequels before they hatch.

We don’t – I don’t know what a sequel would even be now. But I’m finally wrapping my head around this movie, and I feel really good about it, and as we’re getting ready to leave New Mexico in a couple weeks, I’m starting to get a little nostalgic. It was – I don’t do location shows, ever. But this was in the summer, and I felt it demanded it, for the scope. And it was summer, I was able to bring my family with me, and we’ll be shooting the rest of it back in Universal on the stages. And that’s really fun to do those builds. But I have to say, this is a – it’s been a really, really – so far, it’s been as positive experience as I’ve ever had, as far as the material that I’ve had to work with, the producers, the type of support I’ve gotten from the studio; the actors are talented and everybody is really enthusiastic.

And I’ve shown them some stuff and brought them the Comic-Con, and we got a little taste of – you know, we really put something that’s very indicative of the film out there. It was long, it was like ten minutes long. It didn’t rush. We let the western part of it play out. We introduced essentially what the sci-fi part would look like. And we put it out there. And it’s hard to put something out there that early, because if it had been rejected, it would have been hard to really gather ourselves back up and keep pressing forward with all the hard work we had. But we really showed something that was indicative of what I told the actors the movie would be. And then for that crowd to accept it with open arms – being that they had no frame of reference for it whatsoever.

And they really, you know, it’s that kind of enthusiasm that you only get in that kind of environment. It showed us that people liked what we were doing; we were doing what we set out to do. And it just made, ever since then – as hard as it was to get that stuff ready for Comic-Con, and from the first meeting I had with DreamWorks, I said, “We have to figure out a sequence to get ready for this date, and let’s back into that.” So we were working six day weeks, which is very hard on everybody and on ILM, and we got it done.

And after that, it was a real sense of relief and fun, as we came back and everybody’s reading online how it went. And it just was one of those wonderful experiences where even though people had to work that weekend to go there and come back, and there was people who’d never been there before, like Manual and Harrison – It was still – it gave – and really, the crew even more than the cast, got to see that piece and I think that they were excited that they were doing something that they felt proud of. And so the whole experience has been good, and I would – if there’s any way to feel it again, you know, it’s something I wouldn’t run away from – it’s something I would embrace.

Does the importance of it get blown out of proportion, outside of the scale of, you know, the interaction between you and that particular audience?

It depends. If you’re relying solely on that, it’s bad, I think, because it’s – because that group of people will be there. But when you’re dealing with movies of a certain size, you have to appeal beyond that core group. But I think, especially like superhero movies have ignored that core group for so long and said, “Look, that group is just X amount of dollars. We need to get everybody else who’s never read these comic books. So we could change arbitrarily whatever we want to from the comic books.” And I think when Marvel formed their studio, they set out to say, “Hey, let’s not ignore the source material.” And the experience with Iron Man showed me that if you take that base and you build out from it, it’s better than ignoring it because I understand what that group likes.

And if I could, if it could ripple out from that group, then you could let other people like it, too and make it accessible, it’s good. But when you only hit that group, you could be the hit of Comic-Con – it was the same thing in independent films – you could be the hit of a festival, and the minute it hits the multiplexes, the movie dies in the third week; once you platform out, the movie goes away. So the trick is to get that core to like it, and what they’ll do is they’ll at least be vocal about what it is, so if people are curious about the film, the word of mouth will spread out from there. But if those people who hear the word of mouth don’t care about it, it’s not an interesting concept, if they don’t like the people who are in it, then they won’t come.

So you can’t trade one for the other, but I think it’s a great place to start, and the easiest place for me to start because that’s – I share the taste with those people. I don’t share the taste of the people who are in – high school students who are, you know – my head’s not there anymore, right? Like I would want to check out Piranha 3D, but I don’t know that I could make that movie. But I get why it’s appealing, and I would want to check it out, but I wouldn’t want to live two years of my life making it. But I would – but I see movies, you know, I see what they’re doing at Comic-Con, the movies that are a big hit. I see a movie like Tron coming out and it’s getting a big buzz there. That’s a movie I think is cool. That is one I would want to work on. And I actually think that one’s going to spread out from that core group. But because they planted their flag in San Diego and showed the footage, and people who are meeting up on it are hearing it’s good – I think it’s going to – I think it will help reach outside of that.

Since there’s not a lot of westerns being made currently, did either of you have someone that you went to for advice on directing a western or writing westerns or…

Yeah, we had – well, Ron Howard, certainly. You know, with The Missing and Far and Away and just a student of it. And Spielberg knows – he’s encyclopedic with his knowledge of it, and he’s even – I think when he was 16 he met John Ford and got some advice from him. So that’s been it. And then watching them, listening to commentaries. And there’s even like online – I’ve listened to that whole series of online western…mythology of the western –

University Professor of iTunes – yeah.

Yeah. iTunes U. We’ve been listening – if you follow Olivia Wilde’s Twitter, she’s – I turned her on to the iTunes U and she’s been taking like Yale courses in her trailer [laughs]. But there’s a whole series from Wellesley in that. One of Alex’s old professors, his partner’s old professors, would show a western and then talk about the context and the mythology and – studying the genre of the western. So I’ve been hitting it from all ends – just watching them, commentaries, talking to the experts, and then even listening to lectures on it.

In working with Steven Spielberg, I know you’ve mentioned his movies, and Close Encounters a lot of times already. How much of a sense of nostalgia has there been in experiencing shooting this? Or how much are you injecting it into this movie, just from your own, you know –

I think I grew up on it, so it’s in my bones. So that’s my context. And I think you’re seeing a lot of people of my generation – I mean, that’s who we had. That’s what we’ve come up with. Then there’s – Terry Leonard’s our Second Unit Director. And he’s – you know, he worked with John Wayne and Yakima Canutt, you know, all the people that – and he was a stunt man for a long time in westerns. So he’d been around all of it. And as a matter of fact, we hired, well, it was one of his roping partners. Brendon Wayne is here today. That’s John Wayne’s grandson. He’s right there, walking away. There he is – he’s in the yellow striped shirt. So there’s – and then we had the Taylor Brothers, and father. So there’s – and then a lot of these guys, this – you know, when you say you’re doing a western, people are lining up on the stunt man side, the writer’s side – they don’t make westerns.

And there are people who came up doing them. And so we have people from all over the country who came out just to be in this, because you don’t get to make one. And Terry had switched from westerns to car movies, like the Fast and Furious stuff, because in the 70’s, they stopped making the westerns, and he switched over to being a stunt coordinator for car movies. And now to be able to do a western, with all the horse falls and all these things that he knows how to do in his sleep, it’s great to have that resource to tap into. And they’re off shooting right now, while we’re shooting this stuff. So that’s been a really good education, as well.

You talk a lot about alien wonderment, with like E.T. and Close Encounters And then you also talk about alien horror, with Alien, and then you also John Ford with The Searchers, so I’m curious, how dark is this movie going to be? And are you, in a sense, trying to reinvent alien wonderment movies?

Yeah, it’s limiting your power, more than anything, because you can do anything now. So we’re picking a very narrow interpretation of what an alien invasion might be in that time. You know, because it could be Independence Day, where it’s all about how big the ship is and how many ships come in, and how many ordnance that you could have fighting them. Or it could be like Mars Attacks, or it could be you know – the fifties stuff. So it’s picking what version, and limiting ourselves in a way that we would – that technology used to limit those filmmakers.

And as far as the tone of it, I think what’s nice about the piece that we showed at Comic-Con, is I think it shows the marriage. If you could – if you buy that it starts off with the lone rider, and ends with the town blowing up – if that progression doesn’t balk for you, that’s kind of the world of our movie. So it’s – and as a director, my biggest responsibility is tone. And whether I’m making a western or a sci-fi movie, I would still have that responsibility. And I think I found the tone that marries the two. And it’s a balancing act, and that’s what makes this movie work, and that will work. And I think where westerns have failed in recent years is that they got the tone wrong. So, let me go finish making it [laughs].

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.

Law And Order Guest Star Shares What Was 'A Little Embarrassing' While Filming With Reid Scott, And Now I Wish There Were Bloopers

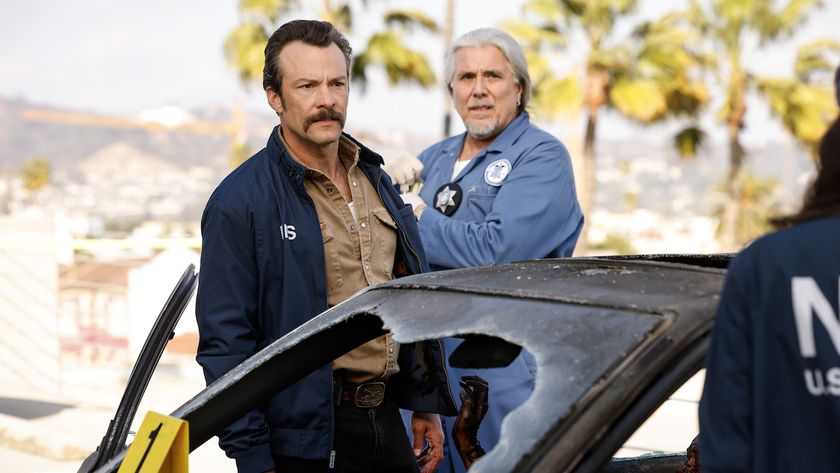

NCIS’ Diona Reasonover Opened Up About The Latest Episode’s Smoky Kiln Scene And More, But I Especially Liked Her Thoughts On Kasie And Knight’s ‘Rock Solid’ Friendship