Every Coen Brothers Movie, Ranked

The Coen Brothers, or just Ethan and Joel to their close pals, have never made a bad film. Sure, there have been disappointments. But in a world where Fifty Shades Of Black and Sinister 2 exist, any film by the idiosyncratic pairing is devoured rapidly by cinephiles.

Hail, Caesar! is their latest effort. And to celebrate its release, I decided to take on the unenviable task of ranking the Coen Brothers collection. It was impossible. And I felt as though I betrayed every single film that didn’t finish number one. Which is exactly why they’re cinema’s favorite siblings.

This was really fucking difficult. I would make the obligatory Sophie’s Choice comparison, but she only had two children to choose from and neither had the complexity of A Serious Man or seemed likely to match the thrills of Fargo. Here's my ranking. What's yours?

17. The Ladykillers

OK, I lied. This part of my list was easy. The Ladykillers is an odd film because it’s not odd. It lacks the usual flair of characterization that normally makes even minor characters in a Coen Brother film memorable. Instead it just feels like a waste of Tom Hanks. As you’d expect, their script is still speedy, tight, and has plenty of laughs, while their direction is slick and moody. But, in comparison to other Coen films, it’s underwhelming. And except for the magnificent Irma P. Hall and J.K. Simmons, the only good to come out of The Ladykillers is that this was the first time Joel and Ethan Coen shared producing and directing credits. Still better than most Hollywood drivel, though.

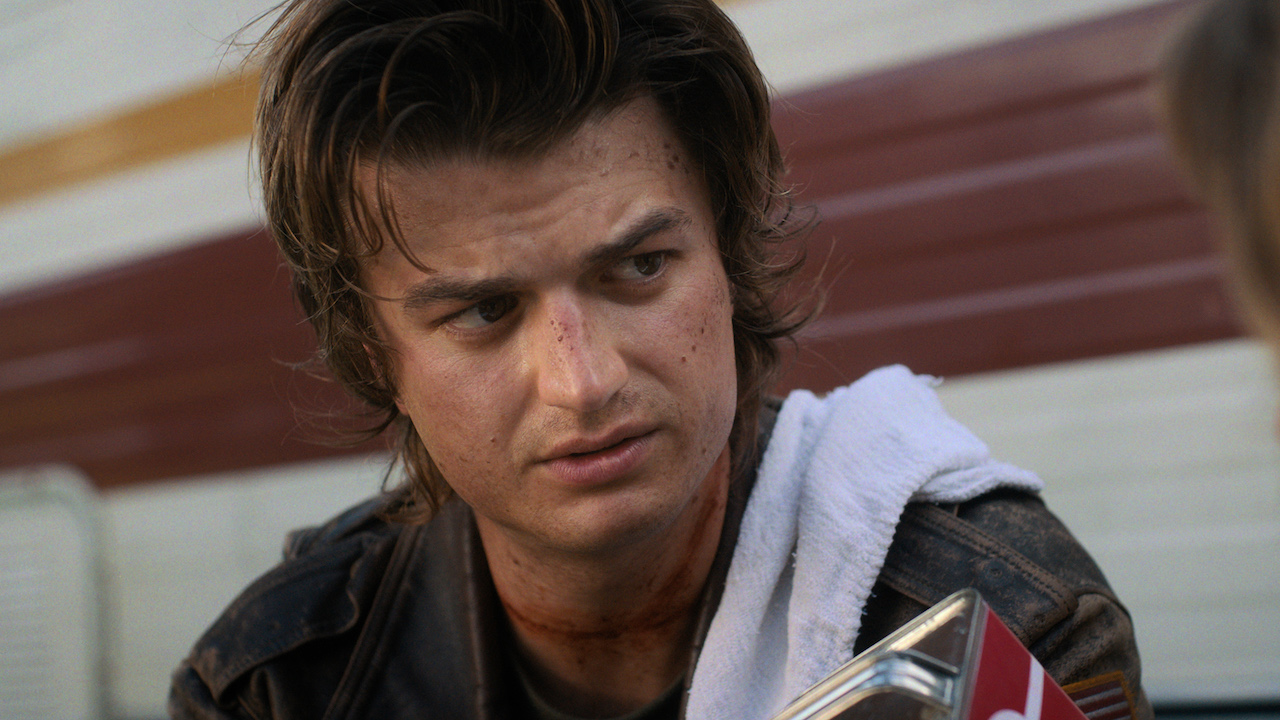

16. Burn After Reading

Fresh off the success of No Country For Old Men, the Coen Brothers could have picked any project that they wanted. With Burn After Reading they went for a screwball spy film, but substituted the explosions for an all-star cast that included George Clooney, John Malkovich, Frances McDormand, Tilda Swinton, Richard Jenkins, Brad Pitt, and J.K. Simmons. Each member of the ensemble revels in the comedic freedom that they’re given. Clooney delivers the Coen’s dialogue with panache, while watching Malkovich erupt with anger is always a joy. But it’s too frivolous and aimless to be up there with the Coen’s best work. It still features one of the pair’s greatest ever final scenes, though.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

15. The Hudsucker Proxy

The Hudsucker Proxy was the Coen Brothers’ first attempt to make a big-budgeted, outright commercial film. It cost them a cool $25 million to make (probably $40 million after marketing), and even starred Paul Newman. The fact then that it only made $3 million at the box office means that it will always be tainted as the Coen Brothers’ biggest flop. But, thanks to its sweet-natured, whimsical tone, grandiose 1950s setting (its meticulous production design is divine) and its proud screwball zaniness (it reeks of Preston Sturges, Frank Capra and Howard Hawks), The Hudsucker Proxy is still enchanting. Jennifer Jason Leigh is particularly revelatory as the spunky Amy Archer. Sure, it’s a little style-over-substance, and rings a bit hollow, especially in its attempt to satire "Big Business." But it’s still enjoyably lightweight, and impossible to hate.

14. Hail, Caesar!

Hail, Caesar! isn’t just a black comedy about the black-list, or a love letter to the Golden Age of Hollywood. It also works as a nifty biopic to the life of legendary studio "fixer," Eddie Mannix. Like Inside Llewyn Davis, we’re placed firmly into the shoes of Mannix and follow him around for a day, which leaves room for a stunning array of cameo performance from Jonah Hill, Scarlett Johansson, Tilda Swinton, Ralph Fiennes, Frances McDormand, Channing Tatum, and even Dolph Lundgren. But, while the cameos keep Hail, Ceasar! buoyant, this really is Josh Brolin’s film. Sure, George Clooney is humorous as the idiotic Baird Whitlock, and special praise needs to be paid to Alden Ehrenreich for his loveable comic turn.

But Brolin carries the entire burden of the film sturdily on his shoulders. More gently witty than laugh-out-loud hilarious, Hail, Caeser! is nevertheless flamboyant and fun throughout and probably the closest they’ll come to Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels, a film they’ve referenced throughout their career. But it lacks the substance or focus to be truly memorable. Seeing the Coens’ versions of a musical, Roman epic, melodrama, aquamusical, and cowboy comedy is worth the price of admission alone, though.

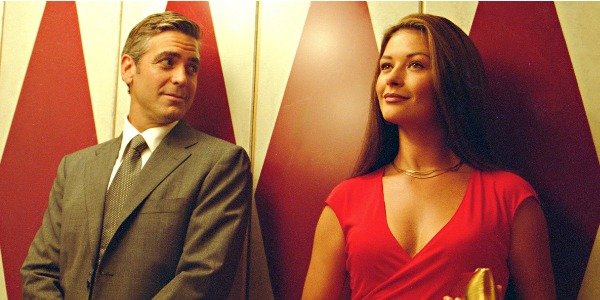

13. Intolerable Cruelty

After The Ladykillers was only met with lukewarm reviews, it was suggested that the Coen Brothers were in a slump. What started this slump? Apparently Intolerable Cruelty. But the fact that this this glossy, riotous romp has garnered a reputation as a crud only highlights just how pristine the Coen Brothers’ filmography is. George Clooney and Catherine Zeta Jones have never looked more glamorous, while Intolerable Cruelty’s pacey script is another example of them tipping their collective hat to the screwball genre. The meandering plot just about tows the line between convoluted and captivating, but it’s also smart, sharp and includes more laugh-out-loud moments than five Hollywood comedies combined.

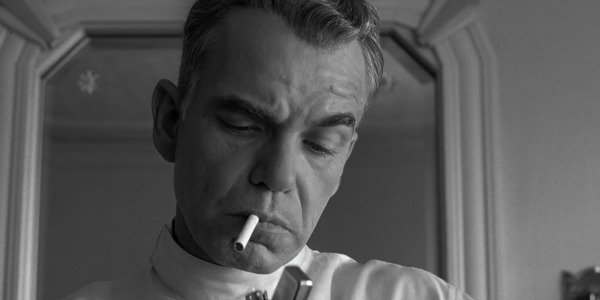

12. The Man Who Wasn't There

The Coen Brothers film that is most often overlooked, which probably has something to do with the fact that its lead character Ed Crane, played almost effortlessly but still affectingly by Billy Bob Thornton, is monosyllabic throughout. Despite its relative anonymity, there’s still an awful lot to admire about The Man Who Wasn’t There. First off, it’s utterly stylish, which is partly down to its use of black and white, with cinematographer Roger Deakins making even the simplest of shots hypnotic to look at. It’s a delightful homage to the film noir genre, as its lead character says little because he has little to say.

It also becomes increasingly bleaker as it progresses, which still doesn’t illicit too much of a response from the constantly passive Ed Crane. Kudos to Michael Badalucco and Tony Shalhoub as the talkative barber and shyster lawyer, respectively, who inject verve and vigor into the film. But, ultimately, The Man Who Wasn’t There is too dispassionate to really leave an impression. Even though it’s a hell of a journey while you are watching.

11. Barton Fink

Here’s the first film on my list that I feel bad for placing so low. The previous six, while each with their own charm, don’t provide the seamless heady mix of humor, poignancy, thrills, and drama that the next Coen Brothers pieces, including Barton Fink, somehow manage. Barton Fink is probably the greatest film ever created about screenwriting and the struggles of Hollywood, as the magnificent John Turturro’s titular character fails to adjust to scribing for the big-screen following his huge success on Broadway. It might not surprise you to learn that Barton Fink was written while the Coen Brothers themselves struggled with writer’s block as they scribed Miller’s Crossing. They took a break, and within a month, Barton Fink was written and ready.

The whole host of ideas that fester throughout Barton Fink is evidence of just how speedily it’s written, which works as both a detriment and a perk. It examines the superficial differences between high and low culture, poking fun at numerous renowned writers along the way, while exploring themes related to fascism, World War II, working in creative industries, and simply being a man. But, most importantly, it’s an art house film that pokes fun at art house films. Which is just deliciously Coen.

10. True Grit

I didn’t like True Grit at first. I expected a rough-and-tumble, standard western that had much more in common with the 1969 original. I was an idiot. It took until my second viewing to realize just how subtle, finely crafted and preposterously well performed it is. If he hadn’t won it the year before, Jeff Bridges would have been a shoe-in for the Best Actor Oscar as his gruff Rooster, while Hailee Steinfeld is a revelation as the peppy, driven Mattie. The Coens have never stayed within the confines of a genre more, while Deakins’ cinematography forgoes the stunning landscape shots in favor of a dusty, dirty aesthetic.

And then there’s Carter Burwell’s score. While working for the Coen Brothers, Carter Burwell has written four themes that immediately encapsulate the mood of the film. Miller’s Crossing, Fargo, Raising Arizona, and True Grit just wouldn’t be as good without Burwell’s music, which immediately elevates the fantastic material. While probably not quite matching his work on Miller’s Crossing, Burwell’s True Grit theme is my second favorite of his Coen scores. It immediately sets a nostalgic tone, but as the melody builds, you begin to envision Hailee Steinfeld’s Mattie Ross charging forward on her duty to avenge her father with Rooster in tow. It’s sad, mournful, but still enchanting. And that’s exactly what True Grit is, too.

9. O Brother, Where Art Thou?

The reason that the likes of The Ladykillers, Intolerable Cruelty, Burn After Reading, and, unfortunately, Hail, Caesar! ultimately feel a little like disappointments, even though there are just a handful of problems in otherwise faultless films, is because of O Brother Where Art Thou? And The Big Lebowski. And Raising Arizona. This trifecta of films is proof that when the Coen brothers do lean towards more lightweight material, they are still able to create fully realized worlds of idiosyncratic characters that repeatedly get into peculiar adventures. O Brother is full of them. From Charles Durning’s Pappy O’Daniel to Daniel von Bargen’s Sheriff Cooley, via John Goodman’s Big Dan, Frank Collison’s Wash, Chris Thomas King’s Tommy Johnson, Michael Badalucco’s George Nelson and Wayne Duvall’s Homer Stokes. O Brother starts off at a breezy pace, somehow still feels oddly poignant, and is just an awful lot of fun to watch.

The music selections by T. Bone Burnett, which immediately set the film’s groove and only become more important, propel the perfectly cast leading trio of George Clooney, John Turturro, and Tim Blake Nelson on their merry jaunt away from incarceration. While Roger Deakins’ sepia-toned cinematography papers over any cracks that even briefly start to manifest. All of which combines to make O Brother, Where Art Thou? the cinematic equivalent of a soothing, warm bath.

8. Blood Simple

Danny Boyle has a theory: "Your first film is always your best film." Blood Simple is a film he often uses in this argument. For him, it will always be the Coen Brothers’ greatest. For most others, it’s simply a raw example of sublime filmmaking talent, which has gone on to be honed meticulously over the subsequent 32 years. Blood Simple even features a whole host of traits that we’ve now come to associate with the Coens. There’s deceit, murder, dark comedy, idiotic characters that are way in over their heads, and even an opening, rambling narration. Sure, it’s now a little dated and flabby. But you’re always aware that you’re under the spell of sublime filmmakers as it manages to mix tense and suspenseful scenes with darkly comic tinges; Marty’s gun not working when it’s aimed at Ray and he’s about to be buried alive being the prime example. Poor Marty. Has there ever been a bigger loser in cinema? No. No, there has not. This tone is why Blood Simple is pitch perfect. Despite its seemingly lowly position on this list, I still understand Danny Boyle’s stance. Because just imagine seeing Blood Simple back in 1984. There was nothing like it. It’d be enough to inspire you to get behind the camera yourself.

7. Miller's Crossing

That cold open. That score. The ‘Danny Boy’ shoot-out sequence where Leo proves he’s still an artist with a Thompson. Just the name Bernie Bernbaum. It really does destroy me that Miller’s Crossing is only seventh on this list. It’s probably the Coen Brothers’ most layered script, with each additional viewing unveiling new lines of dialogue and quips to marvel over. But perhaps what’s most delightful about Miller’s Crossing is that it’s exactly what you’d expect from a Coen Brothers gangster film. It’s surreal, comical, yet still firmly rooted in, while also poking fun at, the genre, with tips of the hat to The Godfather, Cagney, and dozens from its heyday in the 1930s. Plus, it’s finale is a direct homage/rip-off of The Third Man.

So why is it not higher? It’s a little too convoluted – it was so densely plotted the Coen Brothers got writer’s block – and equally self-aware. But that’s also what makes it so intoxicating and unique. From any other filmmaker, it would be the pinnacle of their careers. For the Coen Brothers, it’s close to the norm.

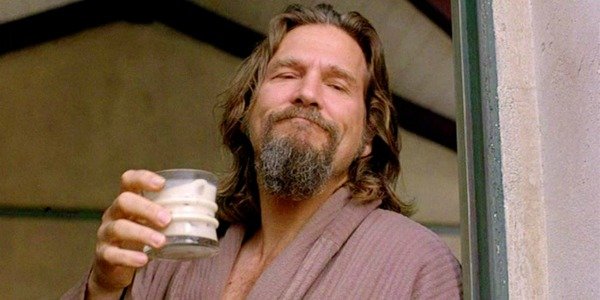

6. The Big Lebowski

By this point The Big Lebowski is more than just a film. It’s a religion. Literally. Of course, to reach this status The Big Lebowski had to do something right. Luckily, it does a whole host of things. It’s the most perfectly cast of the Coen Brothers’ films. It’s literally impossible to imagine anyone else other than Jeff Bridges as The Dude, John Goodman as Walter, and Steve Buscemi as Donny. Just try it. You can’t. It also helps that its mere premise immediately sounds like perfect Coens fodder: as it’s a Raymond Chandler story populated by a bunch of nincompoops, who just want to bowl. The Big Lebowski’s true genius is in the detail that punctuates its dizzying plot, and either drives the narrative forward or proves to be a red herring. I mean, only in a Coen brothers film could a Chandler-inspired tale have a pissed-on rug as the catalyst. While the rambling, forgetful narrator, opening tumbleweed, penis eating ferret, Kenny Rogers tinged musical montage, bag of undies, German nihilists, Donny’s heart attack, Jesus (don’t fuck with him), and funniest cremation scene in cinema history all coagulate to make The Big Lebowski as funny as it is compelling.

Despite its undoubted brilliance, it still doesn’t quite make my top 5 Coen Brothers films. Why? It’s just a little too erratic and outlandish. It’s hardly an excuse, I know. But, when it comes to ranking Coen Brothers films even the slightest issue is enough for a film to pale in comparison against the perfection that's still ahead.

5. Inside Llewyn Davis

No other Coen Brothers film is as rewarding with repeat viewings as Inside Llewyn Davis. Like True Grit, when I immediately left the cinema having originally watched Llewyn I wasn’t sure if I liked it. Unlike True Grit, it only took the car journey home for me to decipher that it was actually genius. All of which is down to its disorientating structure, which leaves you in a state of bewilderment by the time you reach its conclusion. Yet, once you’ve had time to fully ingest Llewyn, it then begins to leave an impact. The titular character is a fine mixture of loathsome, rueful, bitter, and ambitious, and Oscar Isaac is utterly sublime, and almost poetic, in his depiction. Yet, despite his misanthropic ways, Llewyn always resonates.

Inside Llewyn Davis is really about the missed opportunities, the chances not taken, and sometimes being just plain unlucky. Is Llewyn ever going to make it? No. Not to the level that he pines for, anyway. Inside Llewyn Davis leaves more tantalizing questions than resolute answers, but in such a way that only makes in more compelling, and more watchable. And don’t even get me started on the haunting, beautiful soundtrack. In fact, the ultimate proof of its genius is that it somehow made Mumford & Sons seem cool.

4. Fargo

Probably the most important Coen Brothers film in their career. Before Fargo, the pair was seen as part of the cinematic alternative. They were obviously talented, but their attempts to go mainstream were always thwarted by their innate peculiarity. After its release, they’d picked up the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, while Frances McDormand won Best Actress. The decision to preface Fargo with the fabricated text of, "This is a true story," was a blatant attempt to prove that we were now in the real world, not the outlandish Coen universe. Which is interesting, especially when you consider that, rather than being inspired directorially by other filmmakers, the Coens’ main influence for Fargo was Blood Simple, with several scenes feeling as though they’ve been ripped right from their debut.

The real beauty of Fargo is in the writing though. There’s no fat at all to the story. Every single scene feels integral, and it builds seamlessly like a locomotive setting off from the station. The bad guys get their comeuppance. The pregnant cop comes out on top. And it’s the Coen Brothers' most satisfying story to watch unfold.

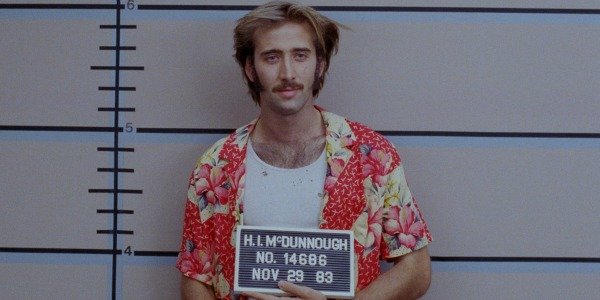

3. Raising Arizona

Raising Arizona is the touchstone of modern comedy. Without it, I’m not even sure if Wes Anderson would have a career, or if The Simpsons would have been as wonderfully irreverent and zany. Twenty-nine years after it was released, it still feels as fresh and hilarious as anything that’s currently in the comedic ether. It’s exuberant, imaginative, and wholesome. In a way, it’s the Coen Brothers’ Goodfellas, as you’re never more aware that they’re in control of the camera. The 10-minute-long opening montage might just be my favorite scene in all of cinema, as it not only sets up jokes that would be oft-repeated throughout the film, but immediately gets you up to speed with Ed and H.I.’s relationship, their problems, hopes and ambitions for a family, and does so in a sympathetic and compassionate way. The line, "I found myself driving past convenience stores that weren’t on the way home," still makes me laugh so brazenly that I might just go ahead and get it etched on my tombstone. And that’s just before the title! But the best thing you can say about Raising Arizona is that once it’s finished, you immediately have the urge to watch it all over again.

2. A Serious Man

The Coen Brothers’ most divisive film. If you love A Serious Man, you’re infatuated by it. If you’re a hater, you long ago dismissed it. Suffice to say, I think it’s their most probing and engrossing work. A Serious Man questions everything, does nothing, and leaves you lost in its haze of existentialism. It can be summed up by the fact that its most action-packed scene takes place off screen, when Sy Ableman dies in a car crash. Instead, as is with life, we’re just left to feel the build-up and repercussions. As the Coen Brothers have done throughout their careers, they infuse their own personal experiences into the story to make it more resonant. (You can immediately picture Ethan stoned at his own Bat Mitzvah).

Yet, they seemingly mock the audience and Larry Gopnik’s pursuit for answers in the process. It’s the darkest comedy they’ve ever created, as every issue Larry faces leaves him more and more lost and puzzled. From the beginning, they look to disorientate with a cold opening set in an Eastern European shtetl that seemingly has no connection to the rest of the film. Was he a dybbuk? Is he dead? We’re left questioning everything. Which just pulls us deeper and deeper in. In the end, it’s probably all connected to Schrodinger’s Cat. I’m damned if I know why, though. And that last shot really is everything.

1. No Country For Old Men

Three years after the disappointing double whammy of Intolerable Cruelty and The Ladykillers, people had begun to dismiss the Coen Brothers. So they went back to the well. In the same way that The Hudsucker Proxy was followed by Fargo, the Coen Brothers’ antidote to The Ladykillers was No Country For Old Men. No Country For Old Men is the Coen Brothers best film because it includes everything you’d hope for in a thriller from the pair. But it’s just done better. It's their equivalent to Revolver. Everything that came before is great, as is everything after, but No Country is seismic while referencing their past work and teasing the future. The shootout and chasing sequences are more thrilling than Fargo, the deaths are more brutal than Blood Simple, the western landscape is more luscious and compelling than True Grit, while its ending is more thought-provoking and impactful than either Inside Llewyn Davis or A Serious Man.

In the same way that Raising Arizona is relentlessly zany, No Country For Old Men is relentlessly tense and only gets tenser. It starts off with Anton Chigurh – Javier Bardem in one of the finest performances in cinematic history - murdering a police officer with his handcuffs, before we then get to see his unique use of a captive bolt pistol to dispatch with the driver of a car he desires. And then it just builds and builds. But not predictably (while it also doesn’t try to surprisingly sideswipe viewers with its narrative deviations) instead it all feels organic. It also feels as though you’re watching the end of civilisation. While it undoubtedly feels as though you're in the presence of one of the greatest films of the last 35 years.

This poll is no longer available.