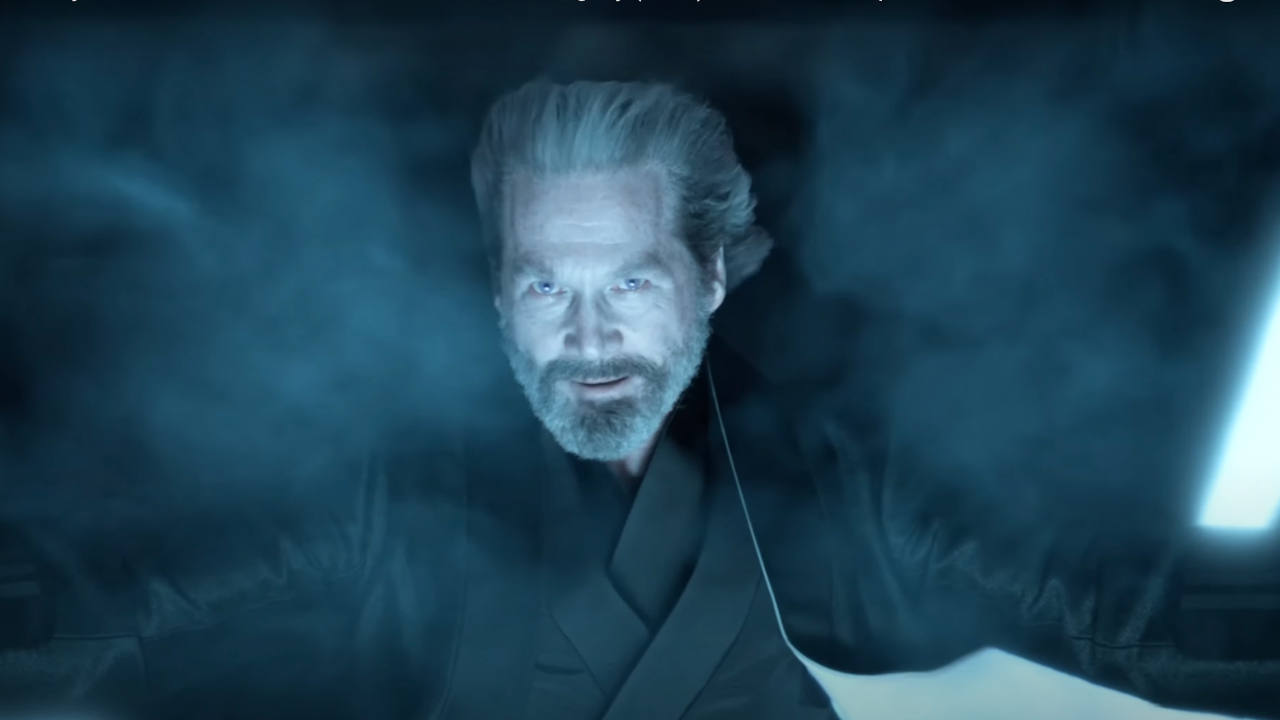

Interview: Tron Legacy's Jeff Bridges

We live in a time when even the mostly mildly successful film is considered for franchising and multiple sequels. Most of the time, however, it takes a minimum of two to three years to see those familiar characters back on screen. Not only has Tron: Legacy taken nearly 30 years to develop, but they managed to bring back their star, Jeff Bridges, as well.

Speaking with the actor as part of a roundtable interview, he discussed his initial hesitance signing up to the project, what it was like seeing himself portrayed as the 28-years-younger Clu and how far technology has taken us since Steven Lisberger’s original film. Check out my interview with Jeff Bridges below.

Was the character always written as a Silicon Valley hippy or did you introduce the Lebowski-ness inside of him?

No, no, that was Lisberger 28 years ago. That was the script, basically, from the original one, and that’s before Lebowski, so I guess you could blame Steven for that.

What were your thoughts when you first saw Clu?

It was amazing. For one thing, what that means, for me as an actor, is that I could play myself at any age now, you know? I love going to movies, but if there’s a movie where a character ages or another actor plays the guy as a younger person, it always kind of bugs a little bit, takes a little while to get up to speed on it. But now, any age. It’s quite remarkable. And they’ll be able to combine actors, I don’t know quite how I feel about this, but that’s coming up to. Just to say, “Let’s get [Bruce] Boxleitner and Bridges and lets put a little [Marlon] Brando in there. See what happens” [laughs]. Then they can hire another actor to drive that image that they created, it’s getting pretty crazy.

Did you have any hesitation about revisiting Tron?

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

I did. I have hesitation making any kind of decision, really in my life. I’m really slow at it. My mothers says that I have aboulia. Have you ever heard of that term? It’s a mental disorder, I guess. I have difficulty making a decision [laughs]. But I really resisted. With this one, I said, “Oh God, are we going to pull it off?” I could see all the technology and everything, but are they going to be able to pull it off right? And Disney did a beautiful job of that. Casting is so important, I think, not only the actors but the director, for one thing – who you get to helm the whole thing. And they got Joe [Kosinski], who had never directed a movie before. Can you imagine the pressure of that? His personality is so calm and sure and then he brings all of his architectural knowledge to the party. So that adds to the whole set design. And he loved the original, and all that, so that’s wonderful.

They also brought Steve Lisberger on board, which I thought was essential, because while the movie can be seen alone and still appreciated, if you saw the first movie it’s not going to bump; there’s going to be a flow between this one and that one. He was sort of the godfather of the whole thing, he was the source. So we would always go back to him and ask him. “Is this consistent with the myth that you started?” And that was everything that brought me to want to do this, because I thought we could use a modern day myth about the challenge of technology and how we’re going to surf that particular wave. Those are tough waters we’re coming into now. We can do some amazing things, but we can also head off in the wrong direction very quickly. This is kind of a cautionary tale, in a way – look ahead and make sure it’s the direction you want to go.

Looking back on the 1982 film and this one, obviously both films were effects heavy, but what were the differences while making each individual film?

Well, that one was shot on 70mm black-and-white and hand-tinted by some ladies in Korea and we were in white leotards and there was black velveteen with white, adhesive tape for the grid lines. And that was basically it. There was some CGI and all of that kind of stuff, but this one – wow, man, they can make movies without cameras. What an idea! When they said that I was like, “What are you talking about?” “You work in the vault.” “What’s that?” It’s a room, it can be any size, paint it green, and there’s no cameras, but there’s hundreds of censors pointing at you. Before each take you “assume the T,” you stand up like this [stands up and spreads his arms out at shoulder level], they get you, and now you’re in the computer. And you’re in a white leotard with dots all over your body, all over your face, you might have a helmet on with cameras. And then everything from makeup, costume, set, and this is the one that kills me, camera angles, is done in post. So we’re in the vault right now in our leotards with our dots on, they can say, “Let’s start the scene way in the back of the room, under the chairs, and come up under the chairs. No, no, no, let’s start here…” It’s all done in post now! It’s crazy!

One of the wild moments in this movie was when I was scanned initially, to get my body into the computer, and it was just like out of the first Tron! You sit there like this and this light just [mimics light scanning over him] [laughs]. It was like for real!

You mentioned that with this technology that you can play any age. Have you warned any of your younger co-stars that you will be competing with them now?

[laughs] No. I hadn’t thought about that. That’s funny.

Are there any other roles that you’d like to revisit?

Maybe. I haven’t thought about it. I haven’t thought about that, but it’s wild to go back there and play different ages. It’s crazy. It opens up a whole world.

Does not having to think about the lens while shooting affect your performance?

Yeah, it was a challenge because I like relating to the lens and I like having a costume and a set. Those are kind of grounding to you. So much of making movies is creating an illusion, and the first person you have to create the illusion for is yourself. So when I have a costume, the person I’m working with is in a costume and there’s a set, that helps me be in those times and be that character. So when you don’t have that stuff you have to kind of go back, it’s almost child-like in a way, when you were a kid and you didn’t have all of the cool gear. You use your imagination. It was a challenge that way. At first it kind of rubbed against my acting fur, it felt odd, I didn’t like it. But in making movies and acting and I think in life too, you can’t spend too much time bitching about the way it is. You have to get with the program as soon as you can, especially when you’re making a movie. So that movie was challenging, but it was a good exercise. And it’s the way it’s going – this is the way it’s going to be.

When you were talking to Clu how did you make that work? Were you talking to a stand-in or a bulb?

We tried it a couple of different ways. I’ve worked with a lot of kids, and when you’re working with kids they have certain hours that they have to work. With a kid they can’t work as many hours as an adult, so often they’ll shoot the kids close-up and then when it comes time for your close-up, he’s gone or gone to school, so you’ll just put a little mark on a C-stand or whatever and do it that way. So I’m kind of used to that, we’d do that. I tried doing it to a monitor, a television monitor, and we’d tried that a little bit.

Can you talk about playing a character that is kind of like a Zen master?

Well, one of my concerns about getting into this movie was that it wouldn’t just be a special-effects movie – that it would have some helpful mythology to it. I’m good friends with a Zen master, a guy named Bernie Glassman – and I guess you put the Roshi in there somewhere, I’m not sure if you put it in there before or after. You might go to his website – zenpeacemaker.com – or just Google “Bernie Glassman” and find out what he’s into. We were just at a wonderful symposium he had, the first symposium of socially-engaged Buddhism which was wonderful. He came on as an advisor and I wanted to add some of the Zen mythology and stories and some of those thoughts and I figured Flynn’s path, what he encounters on the grid coming in, being quite full of himself and that sort of thing, thinking that he can beat Clu and as he says in the movie, the more he goes against him the stronger Clu becomes, so he just decided I have to shhhhh – stop and see if the universe and everything that’s involved will, just like weather, change by itself. He’s applying some of that knowledge. His problem, the way he gets trapped in the absolute, he goes there so far that maybe he’s stopped being able to engage and now his son comes and shakes that all up.

What do you think the cautionary tale is? Because it seems to take two sides – that there’s a danger to freedom and a danger to control.

There’s a wonderful book, and I think it may even be in Flynn’s bookcase, I asked them to put it in there, it’s [Chogyam] Trungpa’s – a Tibetan buddist, and he wrote a book called “The Myth of Freedom.” This idea that “I have to be free, I have to do what I want to do” – you can be a prisoner to you’re preferences. That can be a thing that can just trap you and you’re a slave to it.

What about the search for perfection?

That’s what I’m saying: perfect to who? Whose perfection? And the thinking, “I want it the way that I want it.” That can lead you into a dark, deep place. You have to really think about, “What do I really want?” Like these plastic bottles… oh, good. I asked them not to have them and they don’t have them. Good. Those single-use plastic bottles, and where did that come from? It’s like those things in the magazine, when you open it and those things fall out. Who decided to do that? Or on TV where you see that scroll and all of those little things – come on! We’ve got these bottles now, billions of tons of plastic is in the ocean they say it biodegrades but it doesn’t, really. It just breaks down into small things, the fish eat it, the birds eat it, we eat the fish… it’s bad stuff. I think we’re all hooked, I feel my own hook-ness on immediate gratification you know. I want what I want. I want it now and I can get it now so I’m going to do it dammit, and you gotta watch that, you know what I’m saying?

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.

'I Have That Conversation At Least Once A Week': John Larroquette Talks Waiting On Night Court's Renewal, And I Love His Season 4 Ideas

Andor Season 2's Premiere Showed Mon Mothma In A Drunken Dance Sequence, And The Actress Opened Up To Us About This 'Exploration Of Pain And Chaos'