Interview: WALL-E's Andrew Stanton

Being in a room with Andrew Stanton is somewhat like being in a room with the guy who’s been responsible for making your childhood not suck. Even though all the journalists in the room were most likely over the voting age (myself not included, I’m very proud to say) when Pixar released it’s very first film, the director had everyone in thrall as he talked in depth about how his idea for WALL-E came about. He also talked about the inspiration for his adorable robot, the Pixar brainstorming process, and what Peter Gabriel taught him about his own film.

Why didn’t you wear a Hawaiian shirt?

That’s John’s thing!

Were you looking at your trash compactor one day and just thought that it would make a good movie?

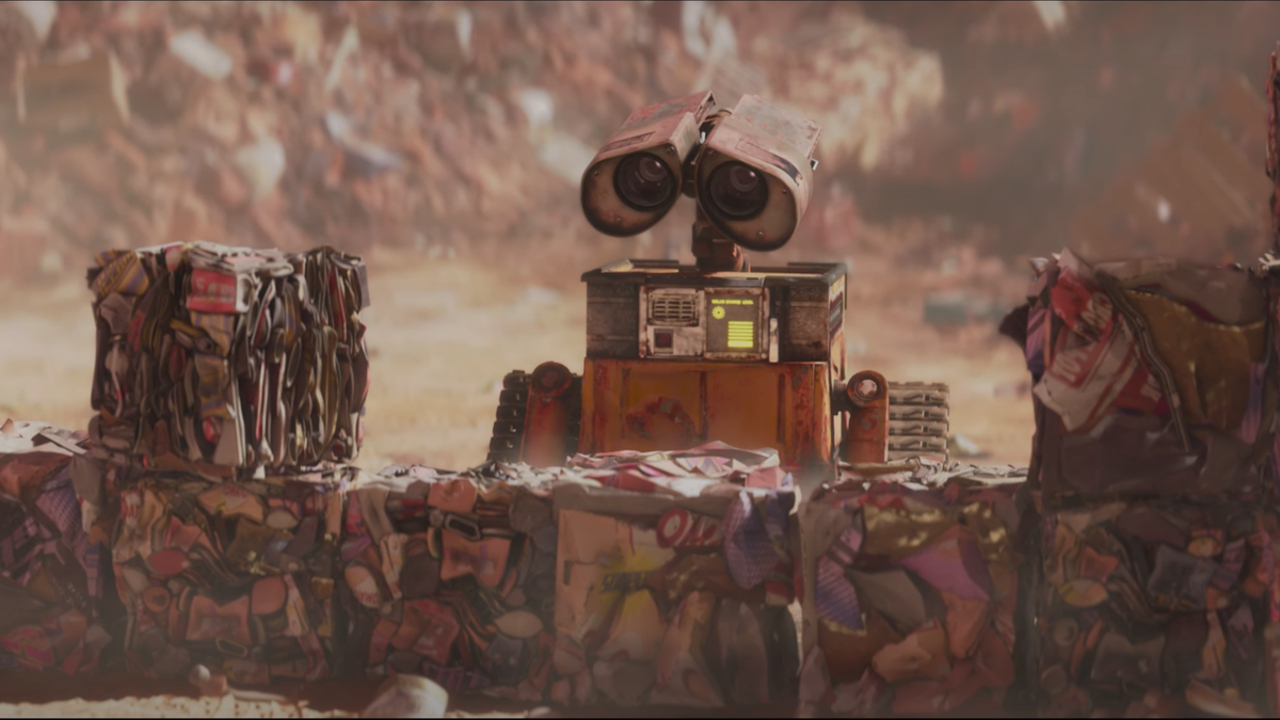

There was this lunch we had during Toy Story around ’94 and we were batting around any idea we could think of to come up with what the next movie could be. One of the half brained sentences was that we could do a sci-fi thing where we had the last robot on earth. Everybody has left and this machine didn’t know it could stop and it keeps doing it forever. That’s really where it started. All the details weren’t there. There wasn’t a name for the character. We didn’t know what it would look like. It was just the loneliest scenario I’d ever heard and I just loved it. I think that’s why it stayed in the ether for so long.

There was another animation movie about robots but they were humanoid and spoke English. You actually had robots that had to communicate in non-human ways. Do you think it’s cheating to make robots seem overly humanistic?

Being a sci-fi geek myself and going to movies all my life, I came to the conclusion that there were really two camps of how robots have been designed. It’s either the tin man, which is a human with metal skin, or it’s an R2D2. It’s a machine that has a function and it’s designed based on that and you read a character into it. I was very interested in going with the machine side because to me that was what was fascinating.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

John had made Luxo Jr., this little short about this little lamp hops around. It’s just an appliance; it’s not even made to look like a character. It’s just happens to be an appliance that you could easily, by it’s own design, throw a character on to it. That short is powerful. I’ve had to watch that thing about 1,000 times. Every time, just before we put it on I think, “Geez I have to watch this again.” And I get caught up every time. There is some unique power to bringing that type of machine to life than other kinds of machines that are designed to look like a character. I started to put it into the category of why we’re so attracted to pets and infants. I think there’s something already appealing about a machine that’s charming but it can’t communicate fully. You almost can’t stop yourself from saying, “I think it likes me. I think it’s hungry. I think it wants to go for a walk.” I think what is does – and I’m getting really geeky here – I think you pull from your own emotional experiences. It becomes twice as powerful. I think that’s why love at first sight works in movies. Nobody says anything. The guy or the girl stares at the other person. That other person walks across the room and you go racing back to when it happened to you. You’re using that personal emotional experience to fuel that moment in the movie. What if you could get a character to do that through the whole movie, just like Luxo does for about a minute in the short? That’s what made us from day one think that it would make a great movie. We didn’t know how hard it would be to achieve, but we knew that if we achieved it that it would be very powerful.

Can you talk about putting facial expressions on a thing that doesn’t have a face?

It’s not that you’re putting anything on it. You’ve got to go find a design that already makes you do it to it. That’s what happened to John with the Luxo lamp. He never designed that. He just happened to see a lamp and I can’t help myself; I see a face on it.

That’s what we did. I was at a baseball game and somebody handed me some binoculars. I hadn’t designed Wall-E yet. I knew he had to compact trash, so I knew he was going to be a box. I knew he was going to collapse to show that he’s shy, but that’s all I had. Honestly, I was thinking of putting a single cone lamp on there because I loved how you read a face into the simplicity of Luxo, but I didn’t think it would hold for 90 minutes. When I got handed the binoculars, I missed the entire inning. I just turned the thing around and started staring at it. I started making it go sad and then happy and then mad. I remembered doing that as a kid with my dad’s binoculars. I thought that it was all there. There was no nose, no mouth. It wasn’t trying to be a face. It just happens to ask that of me when I look at it and that’s it. I couldn’t improve upon that.

Can you talk a little about the devolution about the humans in the film?

I knew what I wanted humanity to be, but I didn’t know how to express it at first. I wanted something to amplify the love story in the film. I’m not one of those people that comes up with a theme and then writes to it. I go with natural things and somewhere halfway I realize what the theme is. I realized that what I was pushing with these two programmed robots was their desire to figure out what the point of living was. It took these really irrational acts of love to discover them against how they were built. And that was my theme: irrational love defeats life’s programming. That’s a perfect metaphor for real life. We all fall into our habits, our routines, our ruts. They’re used quite often, consciously or unconsciously, to avoid living, to avoid doing the messy part of having relationships with other people, of dealing with a person next to us. That’s why we can all be in a room on our cell phones and not have to deal with one another. That’s a perfect amplification of the whole idea of the movie. I wanted to run with science that would logically project that.

So I was talking to John Hicks, who was an advisor to NASA about long term residency in space, he told me that people are still arguing about how to correctly set up space shuttles so that when a human travels to Mars and back they won’t start losing their bones. Disuse atrophy kicks in if you don’t simulate gravity just right the entire time. It’s a form of osteoporosis. You won’t get it back. They’ve had arguments where people have said, “If we don’t get this right, they’re just going to be a big blob!” And I said, “Oh my gosh. That’s perfect!”

I didn’t want it to be off-putting. In a very early version, I actually went so weird I made the humans big blobs of Jell-O. I thought Jell-O was funny. They would just kind of wiggle and stuff. It was sort of a Planet of the Apes conceit where they didn’t even know they were humans anymore and they found that out. It was so bizarre that I had to pull back. I needed more grounding. So as I pulled back, I thought that I didn’t want it to be offensive. But if you didn’t have any reason to do anything any more, if everything had been figured out, and technology made it that easy to never get up – which is kind of happening with my remote in my living room – then it would set in. So I thought I’d make them big babies.

It’s a scientific term actually that Peter Gabriel told me about called neoteny. There’s this belief that nature figures out you don’t have to use some parts of yourself to survive, so why give it you? Why let you grow farther? I thought it was perfect. It was sort of a metaphor a time when it’s time to get up and and grow up a little bit.

But how did they reproduce?

I leave that to your imagination but I did sort of go with Aldous Huxley’s view of the future. That’ll make you have to go read!

Can you tell us about the voice of EVE? I understand she was a Pixar employee.

The one thing Ben Burtt couldn’t simulate himself was a female voice. If it needed to be neutral or male, it was easy for him to be the source of anything that had to have a human element or inflection to it. But because we wanted a very obvious feminine source, fortunately Elissa Knight was one of our in-house Pixar players. We’re in San Francisco and we’re always re-writing our stuff every day, we don’t have access to actors that quickly. So we use people in-house to do stand-in vocal stuff. She had been a stand-in for many movies and was a pretty decent actress. I called her in to do the female stuff and it worked so well and Ben started effecting it, I thought it was so good I didn’t need to look for another actress. That’s frankly that methodology Pixar has had in all their movies. If you look back at our casting, it’s all over the map. We use A-list, B-list, and employees. What’s consistent is that we choose the best voice for the character.

Can you talk about the political message in the film?

I hate to not be able to fuel where you want to go, but it’s not where I was coming from. I knew I was going into that kind of territory, but I didn’t have a particular message to push. I don’t have a political or ecological message. I don’t mind that it supports that view, it’s a good citizen way to be, but everything I wanted to do was based on the love story. I wanted it to be about last robot on earth and I had to get everyone off the planet. I have to do it in a way that you get it out without any dialogue. You have to be able to get it visually in less than a minute. So trash did that. You look at it; you get it. It’s a dump. Even a little kid understands that. It makes Wall-E the lowest on the totem pole and it allows him to sift through everything left on the planet to show that he’s interested in us. I had to look at everything from the point of view of what you could get visually without dialogue to describe it to you. I actually had him find a plant before I knew where the movie was going. The reason I loved that idea is that it’s like the dandelions that push through the sidewalk. Reality forces itself through all this manmade material to exist and that’s Wall-E. He’s this manmade object but he’s got more of a desire to live than the rest of the universe. I felt like he was meeting himself. I couldn’t get rid of it even though I didn’t know what do with it, but it ended up being a great symbol of hope. I just went with something that felt somewhat true.

More than just a love story, the film has a theme of moral responsibility. Was it difficult to make a more layered dilemma for a kid’s film?

It’s actually much easier. If you’re trying to do multiple agendas, you’ll confuse yourself as a storyteller. If you have one purpose, everything else will fall into place.

I was just curious about the Hello, Dolly! motif in the film.

It was the weirdest filmmaking choice I’ve ever made in my life. When I had the idea of putting that song in the beginning of the film, I turned to my wife and said, “This is the weirdest idea I’ve ever had and I’ll be asked why I chose this for the rest of my life.” By the time I had come to terms I realized I was willing to put up with the question for the rest of my life because I really did think it was the best choice. Once thing I wanted early on in the film is that I old fashioned music set against space. I loved the idea of future and past juxtaposed. On the first frame it would seem fresh. I liked that it was firm footing and unconventional. I started looking through stuff and I started going to standards and a lot of standards come from musicals. I got to Hello, Dolly! and when that phrase “out there” came on, just viscerally I thought it worked and out of context it worked. I just couldn’t drop it. I kept putting it and showing a circle of intimate creative friends and I realized why it worked: the song is about two nerdy guys who have never left their small town and just want to go out to the big city for one night, see what life’s all about, and kiss a girl. I thought it was my main character. My co-writer said that Wall-E should just find the actually movie and that would be why he knew it. When you get that kind of gift falling in your lap, you just embrace it.

How hard was it to get the rights for it?

Fortunately it was really early on. Right then I started working on my producers to talk to Fox. I didn’t want to push the idea too far and then not being able to use it.

I was curious about why you used Fred Willard to be the president of BNL?

He’s the most insincere car salesman I could think of.