Interview: Year One Director Harold Ramis

We got an hour with Harold Ramis for our roundtable interview-- an entire hour with the man who directed National Lampoon's Vacation, who was an original Ghostbuster, who helped write Groundhog Day, for god's sake. And though he was on hand to talk about Year One, his new comedy in which he turns Jack Black and Michael Cera into cavemen, Ramis was happy to talk about his entire career, from working with a camel on Vacation to the plans for a new, third Ghostbusters movie. He also gave an amazing, long-winded dissertation on the evolution of New Comedy, which included himself, Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd and other SNL originals, and how it led to the current Judd Apatow crew. Seriously, it was a marvel.

For the sake of clarity, I've divided the interview into sections, starting with the Ghostbusters stuff-- talk about the new video game and the upcoming movie-- and ending with Year One. I promise the whole thing is worth a read-- Ramis has witnessed and shaped the entire evolution of American comedy in the last 25 years, and is happy to talk about it. Year One opens this Friday.

When the idea of the new Ghostbusters came up, were you relieved to hear they went to you guys about it rather than just get a new cast?

There is no they. We are they. Contractually, Columbia has never disputed that we're their partners in ghostbusters. They can't do anything without us, and we can't do anything without them. It always required a unanimous vote with all the principals.

Is that your next project?

For me it's not really a project. I've had fun laying out the story of the new one with Gene and Lee, and they're writing the script.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

How does the new video game fit into the Ghostbusters mythology?

The people who designed the games, they grew up on the movies. There's never been a good Ghostbusters game, and they thought it was time. They came to us with a proposal, and we al signed off. They showed us illustrations and gave us a rough sense of what the plot of the game might be. We all said why not. We consulted at every stage of the game. As they developed it they would show us Animatics and pictures. The script idea was refined and refined until they had a shooting script.

You've worked with a lot of comedians over the years, from SNL to now the Apatow crew. Do you see different approaches among the different comedians? And what did you take away from your first project with Apatow and company?

Well, in general, when I started in comedy there was a great schism. There was old school and new school. Old school were stand-ups who had been conditions in the Borscht Belt and Las Vegas and Hollywood, in the slick Vegas style. And it was kind of generational, the people our parents laughed at. And it could be very funny. When I was 16 I went to a nightclub in Chicago and saw Lenny Bruce live, and he was arrested like on his very next engagement in Chicago. It began this series of arrests and the trials that kind of ended his career and his life. He got so depressed and so serious about it he finally overdosed. Lenny as the beginning of something new, and Mort Soll took a more accurate, political approach to things. But the new comedy did not emerge until Second City. It was the birth of the new comedy. Mort Soll's satire, it allowed for a Lenny Bruce kind of social attitude. They put it on the stage and made it popular. And that's what Lorne Michaels kind of brought to television. The National Lampoon had a big part to play. The Harvard Lampoon was very funny, much broader and crueler than Second City. The Lampoon went national, with the magazine and the stage show and the radio hour. And Lorne Michaels just cherrypicked from Second City and the other companies. But Gilda and John Belushi and Bill were Second CIty, Chevy Chase was Lampoon, Christopher Guest was Lampoon too. So that became the new comedy. Saturday Night announced its arrival on television, Animal House was the first of the films. Caddyshack was the second. Our press junket was such a disaster for Caddyshack. Someone wrote 'If this is the New Hollywood, let's have the Old Hollywood back.' But more than being the New Hollywood, we were the new comedy. I grew up on the Marx brothers and the old Borscht Belt stand-ups, and Judd grew up on the new comedy. Also I'm totally neglecting the British tradition, which has been great. There's a strain there that's very significant. So I'd lost touch with the Judd generation. I knew they were out there, I knew they were talking about our stuff. Judd and I finally met. He says he and Seth stalked me at the Del Ray FIlm Festival, but really, we were in the same hotel, they called me. So they came to my film, The Ice Harvest, and I went to their film, The 40-Year Old Virgin, and we came out as friends. And then Judd asked me to appear in Knocked Up as Seth's father, and that kind of cemented something for both of us. Also I'd already appeared with Judd in Orange County Jake Kasdan was also, even though he was Larry Kasdan's son, he was from the Apatow school. Really Orange County was the beginning, then I cemented my place in their world with Knocked Up. Then I asked Judd to produce this movie with me. That was a desperate attempt to connect with this whole generation.

What do you think the impact of television has been on that generation?

I was raised by TV, but these guys were raised professionally by it, in the sense that they honed their writing skills around a table like this, with a bunch of writers. They're very collaborative. To the same extent that this generation now does mass dating, a bunch of guys and a bunch of girls go out together. And they're constantly in touch, texting each other. There's much more groupthink. This belief in the table as writers. If you have an idea, you put it out to the table. When Judd first came into this project, I already had a first draft of Year One, and he said 'You know, I'd like to bring three or four writers to the table. We'll shoot you some ideas.' I said, 'Fine, invite some writers.' I think 17 writers showed up, if only to look at me. 'Yeah, that's the Animal House guy.'

You've worked with the new generation of comedy when you directed a few episode of The Office. Is that how you met [Year One co-writers] Lee Eisenberg and Gene Stupnitsky, and what was that experience like?

The fact is Gene graduated from the University of Iowa and came to my office that summer to be an intern. So he interned for me, and then started watching my kids for me, just hanging out. He started watching my friends' kids-- he called himself the manny. He's a smart, funny guy, and started writing spec scripts. in the meantime we were having dinner on Martha's Vineyard, and Lee Eisenberg waited on us. He just finished film school. I said that's a smart, funny young fellow, and he never presumed, never asked my e-mail or office address or tried to hand me a script. The next season I was shooting Bedazzled in L.A. and also on a pilot, and Gene came to work as a PA on the pilot, and Lee independently called my office and got on as a PA on Bedazzled. They met in my office, and started writing together, lived together with some other young writers, and started churning out specs. They wrote a good pilot that didn't get produced, but it got them work. It got them on the Office staff. And Greg Daniels, creator of The Office, he knew my stuff, and they were trying to keep the cast happy by bringing in directors who might be fun for them. Gene or Lee suggested me, or my name popped up. As a director on The Office, there's a tremendous weight that comes with directing features. I was being asked to direct a show that had already won an Emmy for Best Comedy. Steve Carell and the cast had already won the Screen Actor's Guild Awards. The cameraman had shot every episode of the show. THe writers of the episode sit with the director and take you through the script. And Greg Daniels watches every shot you take. So I thought, this is not a job, I'm going to sit and watch these guys film an episode of The Office. There's a false humility in that, I made some contributions in each stage. But you can't fail at this job. They won't let you fail.

When you look back at your career, are there things you think you would do differently? Or things that you can't believe you pulled off?

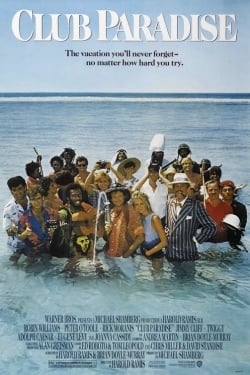

Yeah, someone once said that movies are not finished, they're abandoned. You keep working on it until the studio just rips it from your hands and has to release it. Same with the script. Same every shooting day. You could keep going endlessly on every scene. But as Rodney Dangerfield once said to me, Harold, there's no perfection in life. And he was right. especially in art. Literally you do the best you can. Someone once said to me, every movie you make is three movies-- the movie you set out to make, the movie you think you're making, and the movie you find out you've made. So once you find out what movie you've made, then it's immutable. It's never going to change. I could recut the beginning of Club Paradise now, it could be really cool. of course, no one is asking me to go back and fix it. With every movie, I call it the cringe factor. How many times do I watch my movies and think 'Ugh. I could have done that better.'

With that in mind, in this era of remakes, if you had to do a remake of any of your movies, which would you remake?

I would remake Club Paradise. I thought the story was cool, the setting was great. Everything lined up, except i wrote it for Bill Murray and John Cleese. They were onboard when I wrote it, and when it came time to make it Murray said 'Eh, it feels like I would be the guy from Meatballs, the camp counselor for grownups.' And John Cleese didn't want to leave home, didn't want to be in the West Indies for three or four months, which was what the film required. So Robin Williams was happy to do it, and Peter O'Toole agreed in 24 hours. And that kind of flipped the polarity of it. I wrote it for Bill, who's kind of low-key, and I got Robin, who's completely explosive and all the wall. John Cleese is manic and out of control, and Peter O'Toole is all British control. So once the polarities flipped, the script should have been rewritten for them. But we didn't. I was thinking of Fawlty Towers. My original conceit was to take John Cleese as Basil Fawlty and make him the governor of an island. And Murray I was imagining as a white Rasta, the coolest white guy you've ever seen.

Where do you start making a film like this?

Every film that I've actually written, it starts, it's all in your head. I don't know what it is for people who don't work in comedy, but in comedy, you look forward to the possibility of one, realizing the fantasy you put down on paper, and two, fleshing it out with the funniest, nicest people you can find. 99% of the screenplays that are written don't get produced. But when you write a fantasy, especially an epic fantasy, and responsible adults say 'Yeah, we'll put up the money for this,' it's like, wow, I'm already way ahead.

So how is this different from any other film you've made?

My current work, my new work, is always my favorite work. I always hope it will teach me something I didn't know before. If this was television, and I worked 7 years doing the same show over and over, you pretty much know what to expect. But every feature film, it's like a grand adventure. You go on it with different people every time. Jack Black and Michael Cera are amazing allies to have. I had Judd Apatow not with me, but with me in spirit. Certainly he was an ally back in L.A. It's the nicest job I can imagine having. This film in particular, just the journey itself. I've made one other journey film, National Lampoon's Vacation. It was a lot of fun traveling with the whole crew, like being part of a circus. And the ideas of this film. As silly and broad as this movie is, the intellectual and philosophical underpinnings are so meaningful to me, and gave me a chance to explore these ideas, at least in my own head. Whether they translate or not, I don't know.

So will the sequel be called Year Two?

Our joke was that the sequel would be called Year One Two. When I've been making a film, I've never seriously thought about a sequel. It's not like I needed to explore Bible stories because I think those stories are funny. I was trying to explore Genesis in the context of some political and social ideas that I had, and some psychological ideas. In my mind, having dealt with those, I don't need to do that again. If the public wanted to see more funny Bible stuff, I suppose Sony would get someone else to do the Moses section.

Did you do research, like in the Bible?

Oh yeah, absolutely. A lot of times I find that my research is unintentional. It's more like the work I do is a synthesis of what I've already been reading. The big ideas in the movie I've been thinking about for more than 10 years.

The jokes about circumcision in the movie are great, and you think about it, and you're like "Where did that tradition come from?"

That's what I was thinking. How did people react when Abraham, out of the blue, said 'I think I'm going to cut off my foreskin, and every other in the guy in the village should do so as well.'

What was your research into all this circumcision stuff?

Well two things about that. When we got to the eunuch section, played by Kyle Gass, the second half of Tenacious D. Or the first half of Tenacious D. We already dealt iwth circumcision, and eunuchs have been around for a long time also, and where did that idea come from. People don't laugh, Michael's delivery is not intentionally a joke delivery. But I thought, this is the first time in a movie someone is going to say, what's up with all of the genital mutilation? Which is a real issue, still in parts of the developing world. But what is it? Is there some deep psychological revulsion with our genitalia?

When you get actors like Jack Black and Michael Cera, who are so skilled at improv, what kind of stuff happened in front of the camera that surprised you?

Well, I'm always surprised. Sometimes not happily surprised. But improv's now part of the job. Virtually everyone who's doing comedy today has been trained at one of the improv schools. Jack has that training. Michael's been raised in television. I looked up his IMDB thing, and he was 9 years old when he did his first commercial. But he fell in with all these improvisers, and he's so smart, he can roll with anything. Superbad I'm sure had a lot of improv. So even the stand-ups, it's not so rigid anymore, that you're either stand-up or improv. Most people are crossing over. You know, when you're writing a script, you do your best. At a certain point the studio says, OK, let's make the movie. You're not really finished with your script. It doesn't mean that your last idea is your best idea. So each day, part of my job is to do the script, do it as well as we can do it. Write every idea we can think of. Then turning actors loose completely, and say go.

What makes a good comedy pairing?

There's so many good kinds of teams. It's like every relationship we have with women-- two people who complete each other. You usually bond with someone who's not just like you, who has what you don't have. It's always Mutt and Jeff, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, the straight man and the comic. And if they're both comics, they're different kinds of comics. So Jack and Michael, they're a great physical pairing. When we showed people pictures of them in their wardrobes, people laughed, before they heard a word spoken. It's funny, these two guys. They just look funny. Jack's a human cartoon, even when you see him in the street. He's very big, Jack will just do mug, he'll do anything you ask him to. He'll drop his pants, you don't even have to ask. Michael's so introverted and subtle and real awkward--and yet he's not really an awkward person.

What were their interactions on set, as a result of being so different?

Jack is actually a much more serene person than he appears onscreen, and Michael is much looser and more fun than he appears. And they're both really good musicians, and I play guitar and sing. Our cameraman is a guitarist, so we always had two guitars behind the monitors where we all sit between shots. There was always playing in different combinations. Jack and Michael would sing in close harmony, and improvise music.

There are a couple of situations in which Michael Cera's character gets into trouble with animals, like the snake and the cougar, but we don't see how he gets out of it. Can you talk about that choice?

It's almost not a choice. You know, they warn you if you're going to be a film director, avoid the ABC--- animals, boats and children. Because you can't control them. Of course we wrote a film with animals in every scene, and things for animals to do. When I did the film National Lampoon's Vacation, there's a scene where Chevy is stranded out in the desert. I wanted to have him fall down on the ground and have a guy come by on a camel. We got a camera out from California, and we're rolling, and it's 'Where's the camel?' [And the trainer explains] 'The camel, he's not comfortable walking on the sand.' He's from Burbank. So in this movie, I wanted Michael to be attacked by a cougar. We even had a scene where he's attacked by an eagle. We cut that out. So the cougar-- we had the cougar from Talladega Nights. This cougar worked with Will Ferrell. Even I haven't worked with Will Ferrell. So I said, I need the cougar to walk out on the tree limb, leap from the tree limb to a stuntman, wrestle with the stuntman. So it's the middle of the night, we're shooting. They bring out the cougar, and he won't go out on the tree limb. It was literally 3 in the morning ,and we're standing waiting for the cougar to come out. So we ended up with a CG cougar. You know, not everything in the movie's a choice. A lot of things in film are the result of people doing the best they can under the circumstances.

When you're dealing with a lot of funny actors in background roles, in a movie this big, how do you work with everyone?

It kind of relates to Ghostbusters in a way. Ernie Hudson was new to the comedy world, and being the fourth Ghostbuster, he would have ideas, and he would talk to Ivan Reitman, and Ivan would kind of put him off. I could see how disappointed he was. He said to me, I think Ivan doesn't like me, and I said, no no no, Ivan really likes you, but here's how this works. Bill gets this much money, and is the headliner. Danny gets a little less than Bill, and he's the second headliner. And I get a lot less, and I'm like third, because I actually wrote the script. So you're fourth. So when there's a really wide shot, we're all in it. If the shot's a little less wide, you're out. If it's a two-shot, it's not going to be me and Bill, it's going to be Danny and Bill. So there are pecking orders. I've had day players who, to them, that's their chance, that's their shot. They're playing Hamlet all of a sudden. You can only go so far, there's only so much time. Oliver, for instance, he loves to talk about his character, and it's fun to talk to him. But it's comedy. Someone at Second City said, in comedy, you wear your character lightly, like a hat. You don't want to spend too much time overthinking these things, but you want to give each actor what he needs. In general, most funny films, they're funny because they have great comic performances at the heart of them. Most of them, they know their place in the film. They know the whole thing is not going to stop and revolve around their moment.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend

After I Heard Law And Order’s Hugh Dancy Quote SVU’s Iconic Opening, I Love His Take On 'Betrayal Of The Position’ After The Crossover

I'm A Huge Donnie Darko Fan, And Talking To Beth Grant And Jolene Purdy About Reuniting For The Bondsman Was A More Adorable Experience Than I Expected