Movies

Latest about Movies

-

-

Jason Isaacs Is Sure People Will Forget He Played Lucius Malfoy After The Harry Potter Show Comes Out, And He Explained Why He's Perfectly Fine With That

By Riley Utley Published

-

Fans Have Questions About Whether Zendaya Will Take Tom Holland’s Last Name, And Historian Tom Holland Amusingly Weighed In

By Carly Levy Published

-

The Hunger Games: Sunrise On The Reaping Has Cast The Younger Version Of Philip Seymour Hoffman's Plutarch Heavensbee, And It's A Brilliant Pick

By Sarah El-Mahmoud Published

-

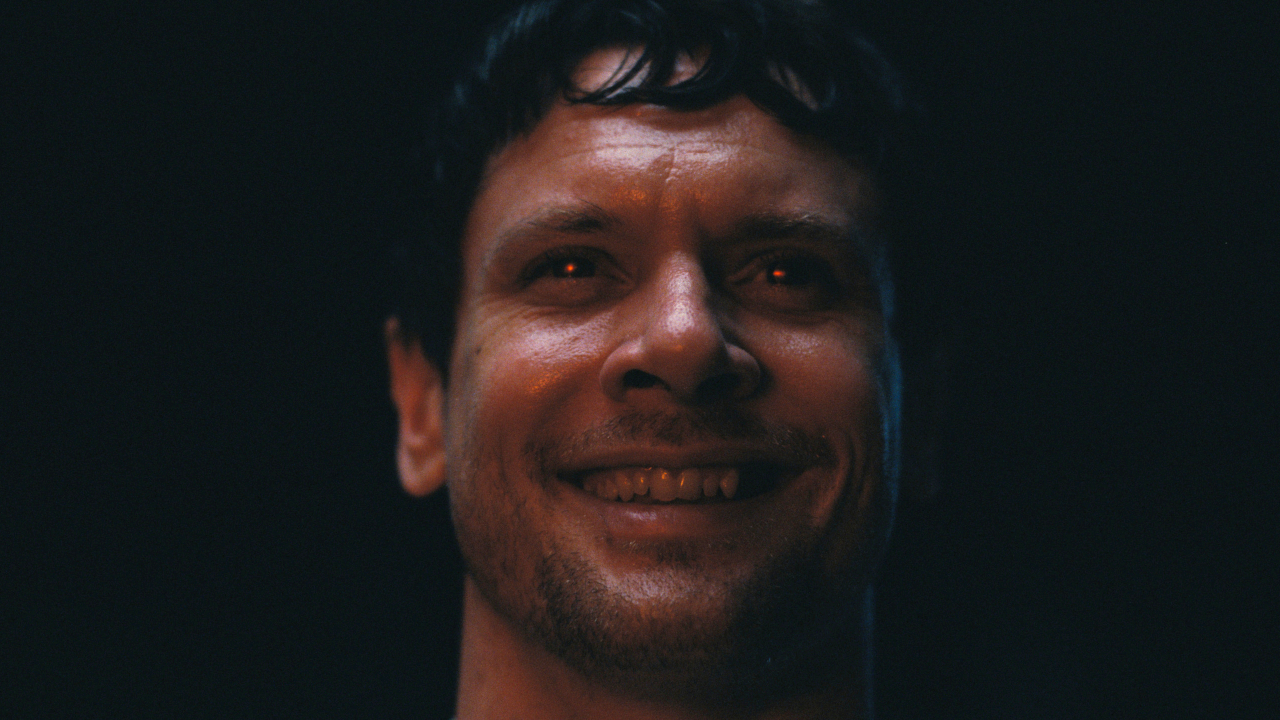

I Can't Get That Irish Jig From Sinners Out Of My Head, And Clearly TikTok Can't Either Based On These Hilarious Viral Videos

By Mike Reyes Published

-

Rachel Zegler Reacted To One Specific Sunrise On The Reaping Cast Announcement, And It's So On-Brand

By Carly Levy Published

-

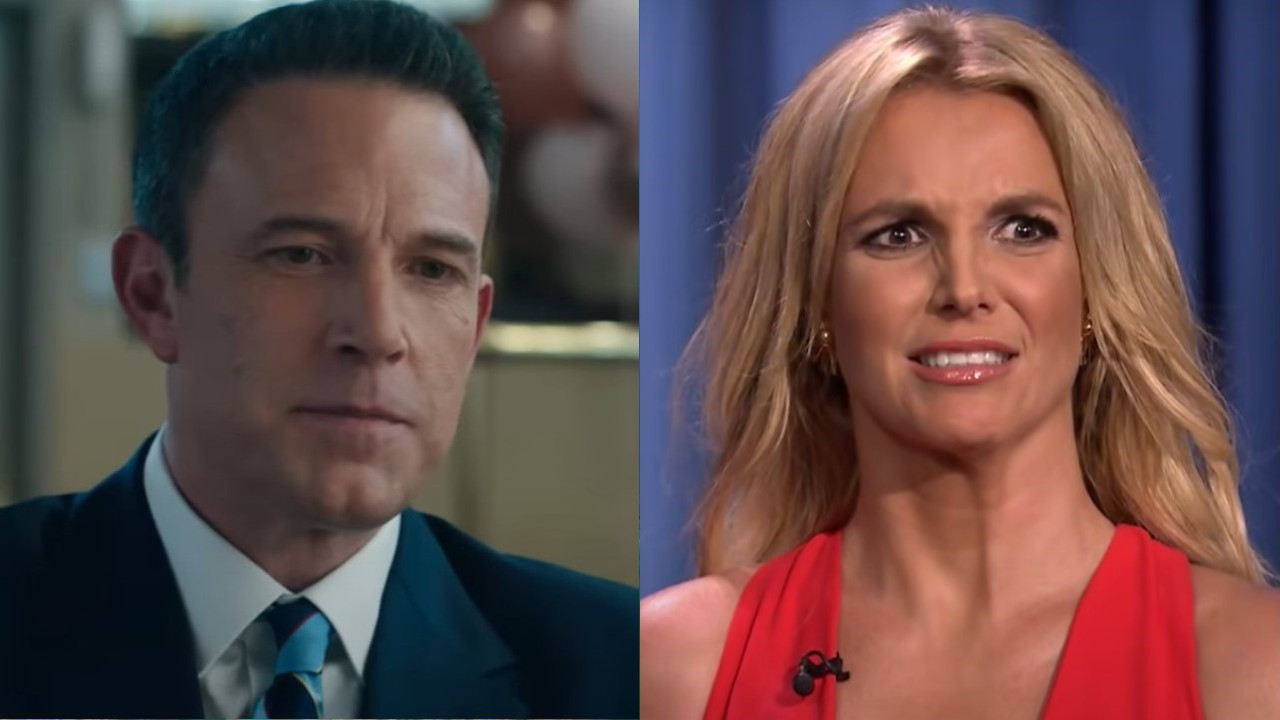

‘A Weird Kind Of Unintentional But Collective Cruelty.’ Ben Affleck Has A Lot Of Empathy For Britney Spears And What She’s Gone Through In The Press

By Dirk Libbey Published

-

The Best Free Movies Online And Where To Watch Them

By Jason Wiese Last updated

-

Explore Movies

Box Office

-

-

Sinners Has A Fantastic Opening Weekend As Michael B. Jordan's Vampire Film Dethrones A Minecraft Movie At The Box Office

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

A Minecraft Movie Dominates The Weekend Box Office Again Amid A Slew Of New Releases

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

A Minecraft Movie Is Just What The 2025 Box Office Needed After A Slow Start To The Year

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

Jason Statham's A Working Man Takes Over The Weekend Box Office As Snow White Takes A Major Fall

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

Disney's Snow White Rules The Box Office As Robert De Niro's New Gangster Movie Flops Hard

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

Jack Quaid's Novocaine Won The Weekend, But The Box Office Numbers For The Top 10 Are Ironically Painful

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

Mickey 17 Wins The Weekend Box Office, But The Numbers Aren't Exactly Stellar

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

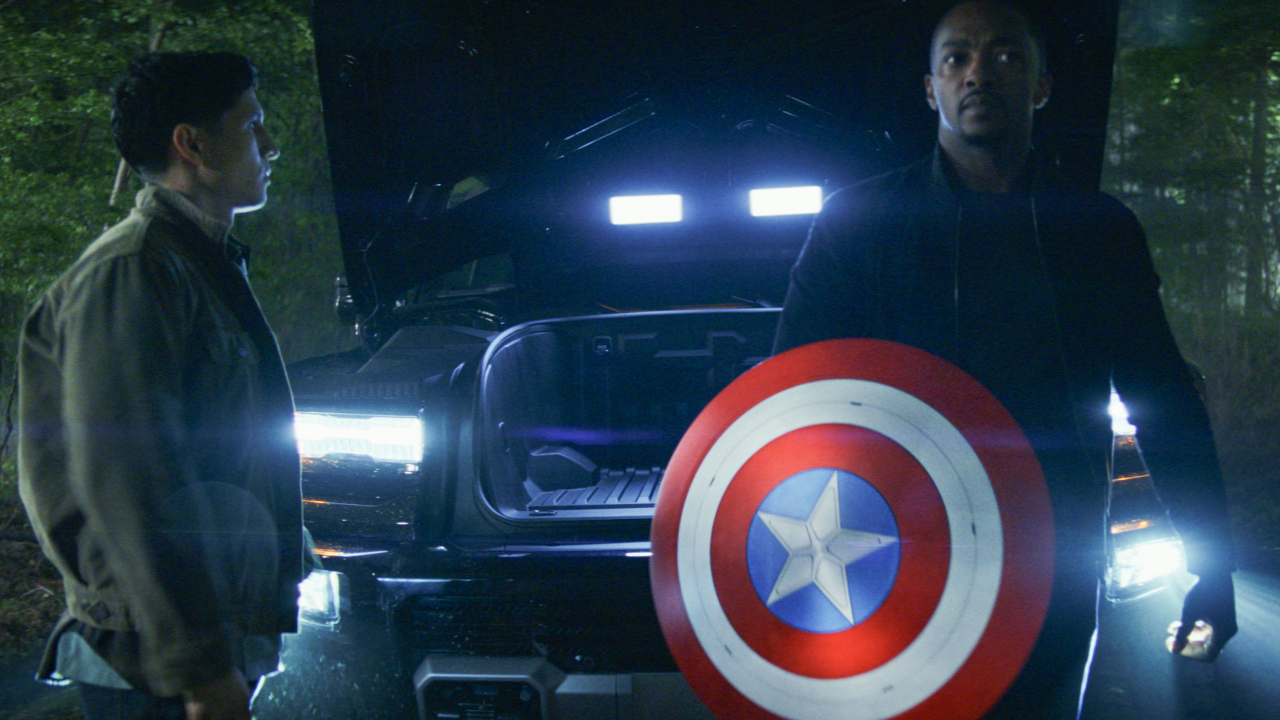

Captain America: Brave New World Won The Box Office Again But Is Still Trying To Break Out Of The Bottom Of MCU's Record Books

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

Captain America: Brave New World Takes A Massive Fall At The Weekend Box Office While The Monkey Has A Strong Debut

By Eric Eisenberg Published

-

Features

-

-

The Best Free Movies Online And Where To Watch Them

By Jason Wiese Last updated

-

Upcoming Book-To-Screen Adaptations: What To Read Before The Movie Or TV Show

By Sarah El-Mahmoud Last updated

-

I Loved Drop And Have To Talk About The Horror Movie's Queerness

By Corey Chichizola Published

-

Upcoming Star Wars Movies And TV Shows

By Eric Eisenberg Last updated

-

Mid-Century Modern Feels Like The Golden Girls Mixed With Will And Grace, And It's Sparking So Much Queer Joy

By Corey Chichizola Published

-

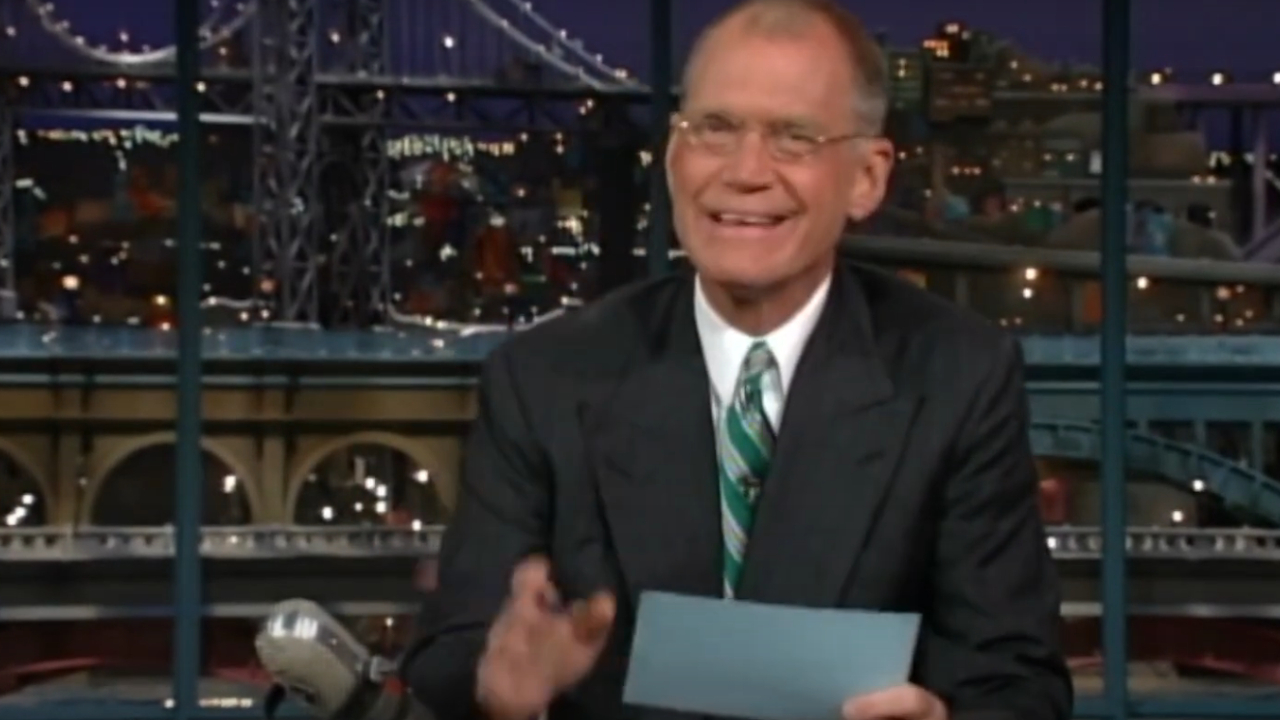

32 Of The Funniest Moments On David Letterman’s Talk Shows

By Jason Wiese Published

-

Upcoming Video Game Movies And TV Shows: The Adaptations Coming In 2025 And Beyond

By Philip Sledge Last updated

-

I'm Excited About The Buffy Reboot Pilot, But There's One Part Of The OG Series It Needs To Include

By Corey Chichizola Published

-

Of All Of The Big Brother Players Who Haven't Played The Traitors, There Are 4 I Especially Want To See

By Jerrica Tisdale Published

-

More about Movies

-

-

The Best Free Movies Online And Where To Watch Them

By Jason Wiese Last updated

-

Upcoming Movies In 2025: New Movie Release Dates

By Jason Wiese Last updated

-

After News That Taylor Swift Might Be Subpoenaed In It Ends With Us Case, An Insider Made Claims About Where Her Friendship With Blake Lively Stands

By Riley Utley Published

-