NYFF: No Country For Old Men

As desolate and dark as the west Texas landscape in which it’s set, the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men is no film for the weak-hearted, either. An admitted weakling when it comes to suspense (see my review of fellow film festival honoree The Orphanage for evidence), I struggled mightily to keep watching, the unbearable tension often only matched by the brutal carnage that followed.

And yet, No Country for Old Men is, dare I say it, funny? It’s been a festival full of drama, a little sex but not much humor, so sitting in a theater full of people laughing feels like a foreign experience at this point. Yet somewhere between the deaths determined by a coin toss and the shots of a dead dog swarmed by flies, the Coens got a few jokes in there, some even at the expense of the psychopathic killer who uses a compressed air tank rather than bullets to the head.

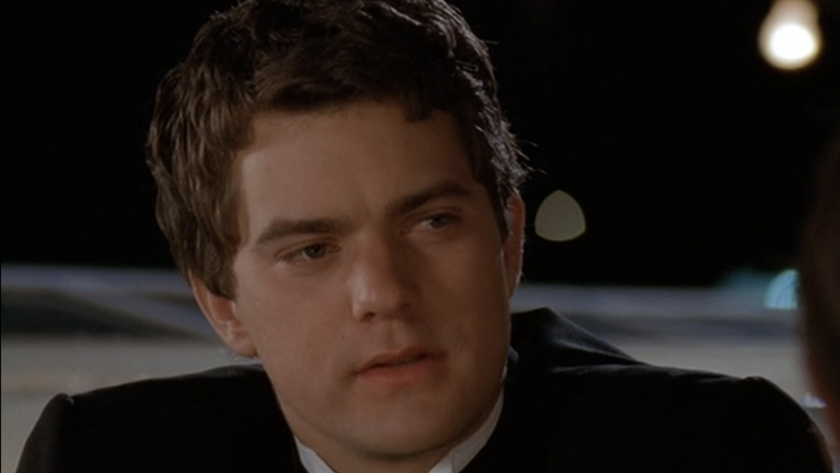

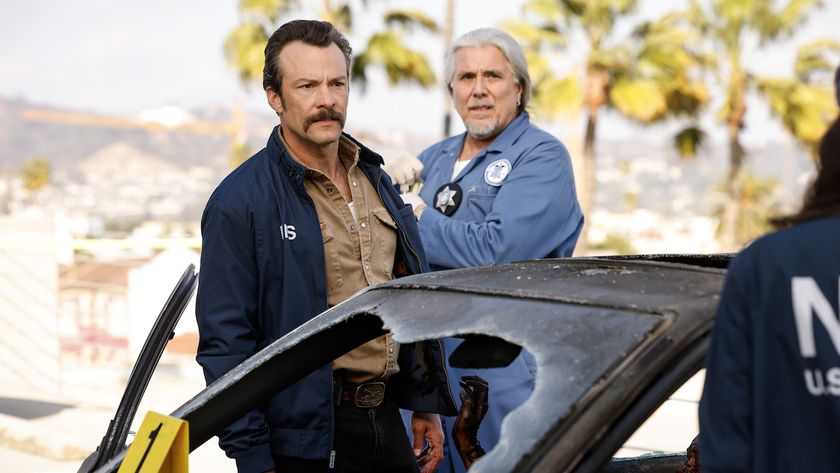

The film is based on the Cormac McCarthy novel of the same name, which gets it title from the Yeats poem “Sailing to Byzantium.” That title is the key to the film’s heart and soul, Sheriff Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), a man too old for his time who is thrown into a sordid plot against his will. He is assigned to protect Llewellyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a Texas good ol’ boy who stumbles upon a crime scene and takes off with a briefcase containing $2 million that he found there. On his tail is Anton Chigurh (Bardem), the kind of ruthless hitman comically embodied by the motorcycle-riding hell demon in the Coens’ Raising Arizona but utterly chilling here. Llwellyn’s wife (Kelly Macdonald) goes into hiding while Llewellyn is on the lam, but neither is safe from the humorless, practically invincible Chigurh.

Every actor in the film puts in marvelous performances, with Bardem a particular standout in a role that may haunt him the rest of his career. Cinematographer Roger Deakins (who also did last month’s The Assassination of Jesse James, showcasing an equally impressive but entirely different West) captures the parched beauty and utter desolation of the west Texas setting, a bleak landscape equal to the cold consciences and uncertain futures on display here. And the Coens direct it all with such an assured hand, throwing in their trademark comedy and delightfully weird minor characters so they seem completely natural in an otherwise dark and ruthless crime thriller. Jones graces the film like an elder statesman, and his character’s conviction that these violent events mark the beginning of a new, unfamiliar era provide the film with levity that pushes it beyond the thrill of the guts and blood and guns. The Coens strongly deny any political intent with the film, but it’s hard not to wonder exactly which country it is that’s changing irrevocably, violently, and quickly.

The press conference following the film was a little jolting, with Brolin and Bardem teasing each other, and Bardem, absent his harsh haircut in the film, actually handsome and appealing. Not to say that I wasn’t still convinced he’d kill me if I called heads or tails wrong.

Javier, how did you wind up with that haircut?

Javier Bardem: I think it was a decision taken by the brothers. I was just the victim. I just [had] to live with it for the next three months.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

So you didn’t come in and ask for it?

JB: I’m not that sick.

The hair is such a vivid aspect of the character, but there’s no description of it in the book. Joel Coen: The idea for the hair, for Javier’s character, was the result of a photograph that we saw of a man […] sitting at a bar in a bordertown whorehouse in 1979. He had that haircut, and very similar clothes to what Javier wore in the movie. It was sort of patterned on that guy.

Mr. Jones, what did you bring to this character, having played many law enforcement officers before?

Tommy Lee Jones: I read Cormac’s book quite a lot, and I read Joel and Ethan’s screenplay quite a lot, and I thought that was the shortest road to originality that I could take.

Joel and Ethan, did you have a clear idea of how you wanted the characters to be? Ethan Coen: I don’t think any of the actors would say we talked to them much, in terms of doing business. We inflicted the hair on Javier and suited everybody up. We kind of trust the actors. For better or worse it’s the actors’ interpretations.

Kelly you’re one of the few women in this very masculine film about men and men’s madness. How was that.

Kelly Macdonald: I got quite a good job because I got to work with everybody. I had great scenes with Tommy, Javier and Josh.

How did you make the transition from the book to the film, especially regarding the ending?

JC: The ending of the movie is taken verbatim from the end of the novel. That was one of the things that interested us when we first read the novel, just as a story, the way that Cormac set up an expectation of a genre piece in a way, and sort of pulled the rug out from under you as you read it.

Can you talk about Roger Deakins’ cinematography, and what discussions you had with him to get a certain light and sense of desolation?

EC: This story takes place in west Texas, and we shot a couple of weeks in west Texas. The parts of the movie where you really see landscapes are in west Texas. The rest of the movie that’s more contained we shot in and around Santa Fe, New Mexico. JC: We discussed this with Tommy, the possibility of shooting the movie in New Mexico, and Tommy said that’d be mistake. When we went down there, we decided that he was right.

There seem to be a lot of references to your previous films—are you conscious of this? EC: We’re not conscious of it, [and] to the extent that we are, we try to avoid it. The similarity to Fargo did occur to us, not that it was a good or a bad thing. That’s the only thing that comes to mind as being reminiscent of our own movies, [and] it is by accident.

Josh, what was the key to unlocking your character?

Josh Brolin: Silence. It’s very rare that you get to play a character that communicates through more body language than dialogue. That’s very difficult for me, because I talk a lot, as everyone here will let you know. The fear is to get caught in a trap of overcompensating for not a lot of dialogue, so you end up scratching when you don’t itch. One of the biggest conversations we had was how much he would talk to himself without looking like he was going insane. Little things like that, that I’ve never had a conversation with filmmakers about ever, in 23 years of doing this.

Javier, did you try to be dangerous even when you were off-screen, to stay in character?

Bardem: I was in character, even if I didn’t want to [be], because when I woke up and I took a shower, and I looked at myself in the mirror, I had the same haircut. When you go to buy milk, people get quite frightened. I have Josh here, and I was talking often to him, and a lot of times I felt like I wanted to kill him for sure. Brolin: Javier got his haircut, and we went to the Cowgirl Café, which is a lesbian bar in Santa Fe. He was kind of depressed and he said “I’m not going to get laid for three months!”

The book is like the dead end of what McCarthy could find from the western. Can there be a western anymore? Where do you see the Western today?

TLJ: I have a hard time figuring out what a Western means. I think it means big hats and horses and dust and has something to do with the 19th century. It’s really hard for me to speak to the idea of there being a genre called Western that can get old and die. I really like making movies that are set in my home (Jones was born in San Saba, Texas), and I’m really interested in the history of my home, and I like horses, and I’ve got a lot of big hats. JC: I agree. It’s hard to know exactly what a traditional Western means when you use that term. We didn’t particularly look at this movie as a Western in quotation marks.

Kelly, how hard was it to master the Texas accent? [Macdonald is from Glasgow, Scotland]. How long did that take?

KM: I’m from Glasgow, Texas. I’ve got a very good friend who’s a dialect coach, and when I first went in to meet [casting director] Ellen Chenoweth I was in New York, and I spoke to my good friend for a half hour or so in the hotel bathroom, and I went in to see her and it kind of just clicked, and I don’t know why. I could just hear a voice when I read it.

Javier, what aspects of being a psychopathic killer attracted you?

Bardem: I guess the fun of working with [the Coens], it is something that for a Spanish actor is impossible to even imagine. I was truly honored by the fact that it could be possible [to work with the Coens]. I had some problems with the character because, as I say, in Europe we don’t have problems having the sexy movies, but we give a second thought as soon as we get a gun. It took like one second for me to say yes [to the Coens]. From there, I thought it was just fun to be there and kill people, go back to the motel and sleep.

This is your first film which is a direct adaptation-- why now?

JC: We’ve written adaptations of other novels before, both for other people and for ourselves. This is the first opportunity we got with something we were very interested in that actually came to fruition. That’s entirely because of Scott Rudin, the producer who brought us the Cormac McCarthy novel when it was in galleys and asked us to read it.

The Texas dialogue seems is so spot-on—how did you achieve that?

TLJ: It’s much to Joel and Ethan’s credit that they took the language out of the book and didn’t try to [change it]. Someone who can read the poetry in Cormac’s work is going to do well. It’s a really good thing that Joel and Ethan can read. JC: It’s one of the hallmarks of his writing. If you respond to Cormac’s novels, you respond to the way people speak.

Javier, is it fun to kill people?

Bardem: It’s not something that I really have fun with especially. I remember one day in the motel, when I kill the three guys…we shot that and then we came back for the room for the next day…I walked in and all the blood was on the walls, and I almost vomited. And I’m there to play the bad guy, so it’s weird.

In this book and The Road, Cormac has a depressing view of humanity. Do you feel your film is reflecting on America at this time?

EC: I don’t think any of us read it as political commentary or as addressing current events. That’s certainly not our thing, [and] I don’t think it’s Cormac’s thing either. JC: I don’t want to speak for Cormac but it’s the way we read the novel […] I think the concerns of the novel were not particularly concern of the contemporary political situation. I think the ideas were more outside of that. EC: Barry Corbin’s [character] was mentioning in the novel as in the movie, he rebukes Tommy’s character for thinking his concerns are particularly to him or his time.

With so many scenes in empty or desolate places, was it difficult having the camera in your face?

Brolin: I think we were more worried about Joel and Ethan not being in our face than the camera being in our face. But the silence…after your thousandth look to the left and to the right, you want to make sure it’s not going to be hollow after doing it for three months. I think the biggest challenge was just to stay present and to make sure we were fulfilling the moment appropriately. Bardem: I was happy, as long as I [didn’t] have to speak, I was happy. If they asked me to speak I had a problem.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend