On The Set Of White House Down, Joining Channing Tatum On An Epic Race From Script To Screen

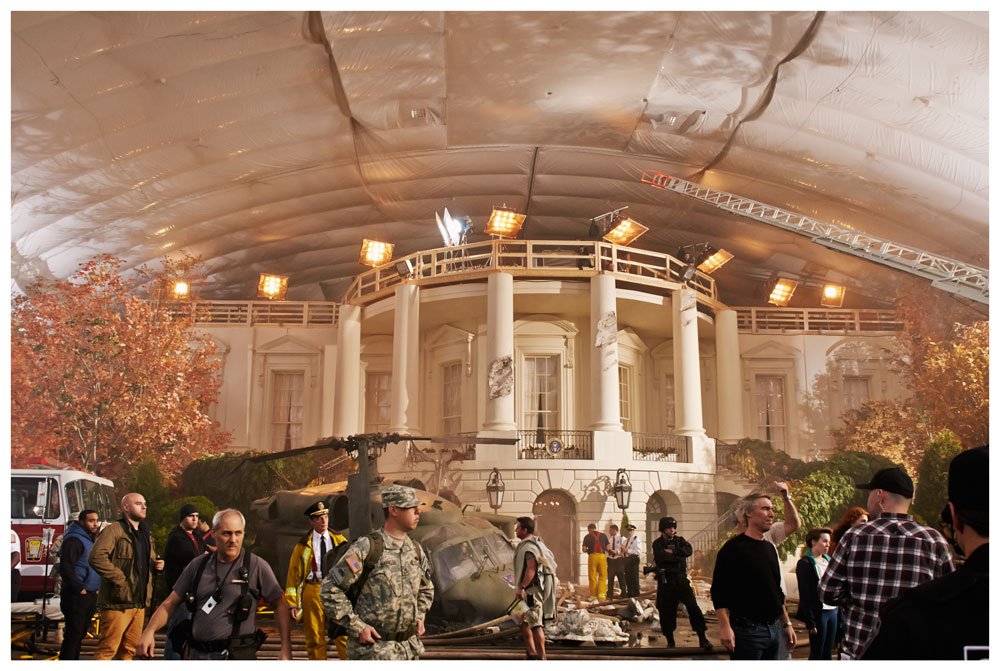

It was a chilly day in September when a small team of bloggers—myself included—strode into the White House up in Montreal. Okay, so it wasn't the real White House, but the makers of this "Die Hard at the White House" movie defy you to notice the difference as they barrel audiences through their high-octane action-adventure White House Down. Director Roland Emmerich is notorious for destroying this particular historical landmark. "(In Independence Day,) he blew it up," Emmerich's longtime producer and composer Harald Kloser offered, "In 2012, we had an aircraft carrier crash into it. And, now, this is actually the best movie for the White House, because it survives." Still, a tour of the sets and a fascinating conversation with production designer Kirk Petruccelli—another frequent Emmerich collaborator—revealed 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue will see plenty of damage.

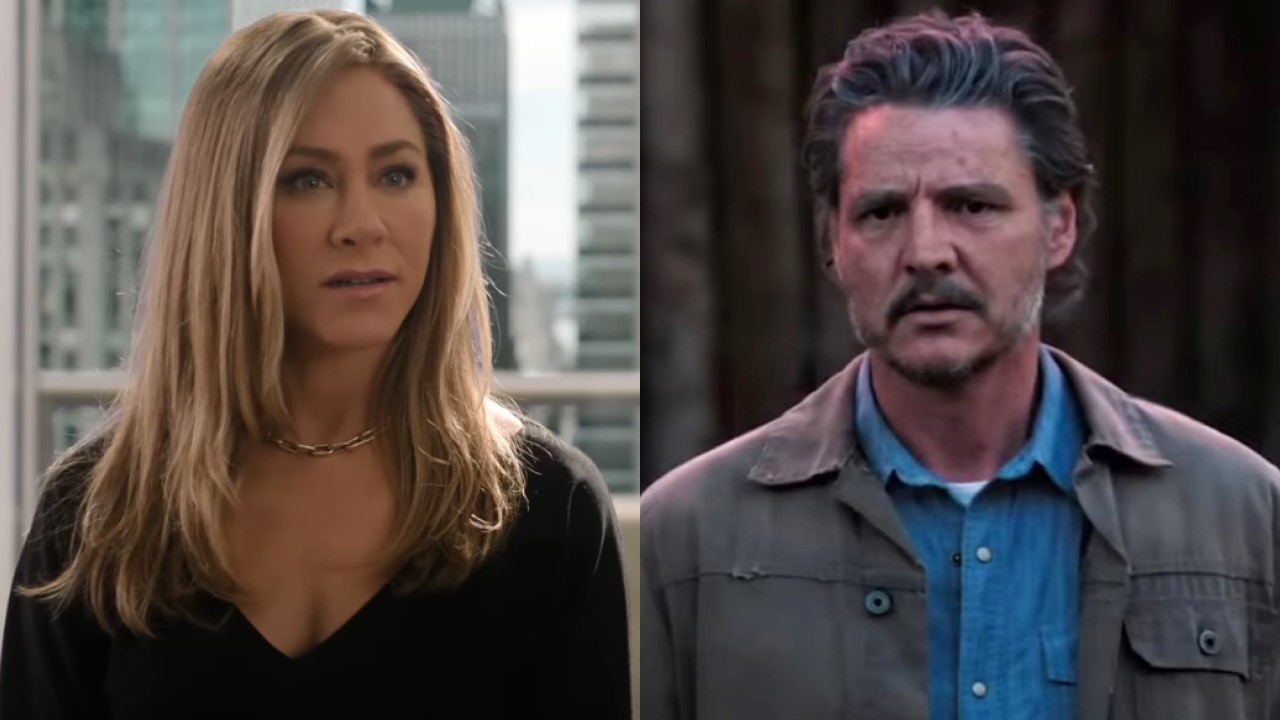

White House Down stars Channing Tatum as Officer John Cale, a character whose name, profession, and preference for white tank tops are just a few of the allusions to his inspiration, Die Hard's John McClane. Like McClane, Cale is a cop trapped in a David vs. Goliath scenario, in his case single-handedly protecting the President of the United States when Washington D.C. and the White House are under attack by a mysterious mercenary force. Jamie Foxx stars as POTUS, while Jason Clarke plays the leader of this invading enemy.

You can see some of the insane action this premise entails in the film's first trailer. But perhaps more extraordinary than its plotline is White House Down's lightning fast path from script to screen in a span of just 14 months! Kloser understandably compared the production's demanding schedule to a race, while producer Brad Fischer says the short lead-time is "a testament to (James Vanderbilt's) script. It's a testament to Sony's desire to work with Roland again, and Channing. It's come together in a great way." But it wasn't just a question of enthusiasm. Pulling the project together this fast was a necessity to score the casting coup that is Tatum, who at the time he was cast was already poised to be Hollywood's newest A-lister.

Sony exec Amy Pascal was the one who contacted Tatum's producing partner Reid Carolin about White House Down. At the time, Magic Mike was in post-production, and Steven Soderbergh's Side Effects (then called Bitter Pill) was close to wrapping. Carolin explains, "(Amy) said, 'Would Channing be interested in meeting Roland?' And I said, 'Yeah, of course!' Roland was literally on his way to the airport to fly to Germany…we're making all these calls so that he could divert his flight, land in New York, meet Channing in like seven in the morning for a coffee at his hotel, and see if they liked each other, and then get back on the plane and keeping going to Germany." The two men hit it off, and then it was up to White House Down's producers to figure out a shooting schedule that could fit into Tatum's fast-filling dance card.

White House Down was eying a shoot in late October, early November. But then Tatum's next project, the Bennett Miller drama Foxcatcher shifted its dates, forcing producers to make a tough decision. In order to make their pre-ordained 2014 release date, they'd either have to dump Tatum or push production forward by seven weeks. That cut the prep time for Petruccelli and his army of craftsman nearly in half! With almost 100% of the production shot on stages, this is herculean task called for Petrucelli's team to build 65% of the White House residence, the South Lawn, pool, West and East Wings, the Kennedy Gardens, a greenhouse, the secretive Presidential Emergency Operations Center, as well as sets for The Capitol, The Pentagon, and two the Oval Offices in just eight weeks. Fischer declared Petruccelli "the hero of our film for being able to pull all these sets together as quickly and well as he did."

By Petruccelli's count, that is 45 sets, constructed by an international crew of 32 designers, and hundreds of craftsmen, who sought to recreate what is known of the White House's interior and exterior down to the finest detail. This army of craftsmen and designers worked around the clock seven days a week, building sets from scratch, then scrapping them and building a new set in its place again as soon as a location was wrapped. Wandering from one stage space to the next, I was astonished as we moved from the roof of the White House, past the remnants of the South Lawn, through the buzz of saws and flurry of sawdust to an in-construction Oval Office. Realizing this is as close to the hallowed room as I'd ever be, my jaw dropped in complete awe to Petrucelli's apparent delight.

Even in its rough state of construction without paint or set dressing, the attention to detail on all its moldings—precisely and individually fitted—was literally breathtaking. Here Petruccelli pointed out some of the specifics of the set's recreation before explaining that some liberties on layout of rooms had to be taken to accommodate the space afforded in the soundstages, but biggest differences from the actual White House were made to better accommodate Emmerich's vision of the place. This meant eschewing its traditional rugs for glossy wooden floors and speaking in depth with Jamie Foxx about his character to decide what touches his president would bring to this hallowed home.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

As we toured the sets with the elated designer, I realized that he—as well as everyone else we spoke with—practically radiated with the sheer joy over this project. It reminded me of my days in regional theater, where the air was filled with a contagious enthusiasm of the "let's put on a show" variety. Fischer echoed this ambience, calling Emmerich "one of the most collaborative filmmakers that I’ve ever worked with," adding there's no ego to his decision, "The best idea wins. And it’s pretty great." It was impossible not to be caught up in this stages-wide enthusiasm. Full disclosure: this reporter took the opportunity to skip through "The White House."

The White House Historical Society, Petricelli explained, was essential in research for the White House sets' construction and design. Of course some elements of the real White House not even the Society could help him with. Though Emmerich and Petruccelli toured the White House three times (twice on the public tour, and once a more private tour) they were never allowed to take pictures nor granted access to the bowels of the building that serve as a bunker in case the president is under attack. Likewise peeks at the PEOC (Presidential Emergency Operations Center) and the interior of "The Beast"—a custom-made limousine specially designed for President Obama with intense but unknown protective measures—were off limits. But Petruccelli has attempted to reverse engineer these locations with a touch of swagger:

"We're anticipating what's possible, what's probable and trying to add a bit of style to it if you want to say that. Just enough to say it's cool. But it's all based in reality. Every question I ask everybody of my team is: 'Why? How? Why would it be that way?' And Roland asks me the same questions…. Everything is the technologies that exist now."

But for all the detail and hard work he and his team have put in, Petruccelli recognizes that if he did his job right, no one will notice his efforts. "If I disappear behind the canvas and no one knows we did anything, my team and I will know that we've done our job well," Petruccelli confessed, "And that's the thing that's somewhat—you just have to understand that because no one will ever pat me on the back because they shouldn't. It should be seamless. (People should think,) 'They shot at the White House! How'd they do that?' To me, that's success."

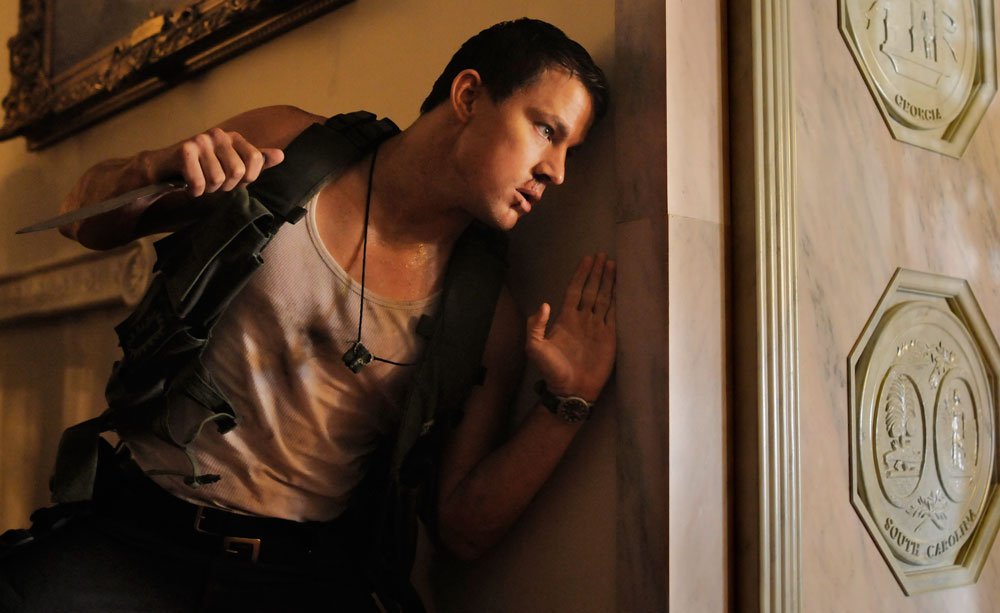

All this remarkably intricate detail work serves as foundation for Tatum, Foxx and Clarke to unleash themselves in potentially epic action sequences. I visited on shoot day #33 of 82, when Emmerich's team was preparing for a pivotal fight scene, the first face off between Tatum's strapping Capitol cop and Clarke's sneering mercenary. The complicated fight choreography plays out atop a sprawling set made to look like the roof of the White House. Wind machines blared as Tatum—dressed much as he is in the film's promo poster--barrels into Clarke who is aiming a Javelin—a sort of heat seeking missile launcher—at a hovering helicopter—well, where one will be added via CGI.

In the scene, the two must dodge bullets and an explosion's debris while keeping up a rugged cat and mouse chase. Each time "action" was called Tatum and Clarke threw themselves literally full-bodied into the action again and again, burly shoulders hammering elbows into each other's strong jaws. In between takes, Tatum danced or bounced to keep his adrenaline going. With Magic Mike still fresh in my mind, I marveled at seeing Tatum's trademark physicality in action live. It was easy to see why in our interview Emmerich had called him, "The most physical actor I have ever met in my life."

Tatum's friend and business partner Carolin explained it this way:

"When you work with Channing, you really realize there’s very few actors working today that can do what he can do. I mean you see when he does Magic Mike, he can move like nobody else in his age group. And you only have so much time when you’re a young actor like that before your body just starts not being able to do it. And you watch him do these stunts, he’s flipping around and doing crazy stuff, like he did a bit in his small part in Haywire. And I just felt like we’ve gotta seize the opportunity and do one of these things because action movies are action movies. They’re super fun and they’ve got a certain formula to make them work. But when you have somebody in the role who can make you believe in them but also do the physical stuff, that’s really rare."

Though he had a stunt double—with a strong square jaw that made him a dead ringer for heroes of the 1980s videogame Contra--Tatum did every take I saw himself. It's a point of pride for him, Emmerich told us, "He did every stunt himself…I mean you have to talk him out of a stunt and the only way you can talk him out of a stunt is like 'It’s really high risk and you don’t see his face.' He’s always very concerned that you see his face, because he’s very proud that he does his own stunts. And it’s a little bit lost in the last ten years that people are proud of doing it. But it’s actually when you see him doing it, it’s like 'Oh yeah, this is the real thing.' There’s no face replacement. It’s Channing and you could not do that many face replacements anywhere, so it’s cool. I like it."

That day a point of contention between the director and his star was over one stunt in particular, one that Tatum told us he desperately wanted to do. "They’re still trying to talk me out of one stunt. I’m going to look at it and if I think I can do it. It’s just a fall, a 25-foot fall, but the way you have to fall is bad because you have to fall on your side or on your back and that’s always dangerous," Tatum admitted. "Yeah, that’s the only one questionable. Everything else will be me. I like doing this stuff though, it’s kind of the whole reason that you want to do the movie. When you’re reading it you’re like, 'Oh, I get to dive out a window? Cool! I get to jump off a building? Great!' So I love doing that stuff."

In a move more common for dance movies than action flicks, Emmerich and his longtime cinematographer Anna Foerster are using wide lenses to better capture Tatum's endless energy and seriously stunning physical prowess. Though the VFX and editing teams were on site, already hard at work to be sure film hits its summer deadline, I didn't get a look at edited footage of Tatum in action. But I am eager to see the wide coverage applied to Emmerich's ambitious adventure. Really, this could be Emmerich's biggest movie yet. I mean, it is the White House after all. As Kloser surmised, "It's like the White House is the one symbol in the world that as a building represents power, freedom, really democracy. This is all embodied in this one house. I mean, I don't know, what other symbol would be there if you wanted to say, 'This symbolizes the Western free world.' I wouldn't know anything else. If you play with those big ideas, you always somehow end up at the White House."

White House Down opens June 28th 2013. For more on the film, check out our interviews with Tatum and Emmerich. You can also see a ton of new images from the film in the photo gallery below.

Staff writer at CinemaBlend.