Adapting Stephen King's Weeds And The Crate: Is 1982's Creepshow Still In Mint Condition?

If it weren’t for the fact that Stephen King’s The Stand is such a crazy nightmare to turn into a movie, it’s possible that we wouldn’t have Creepshow. After all, the origin of the beloved anthology begins in 1979 when George A. Romero got the itch to adapt the pandemic epic (which had been published the previous year). Of course, it didn’t take long for the two men to recognize the very real challenges that making the film would pose. Desiring the Hollywood Holy Grail mixture of substantial financial resources and creative control, they opted to focus their efforts on a different project that would hopefully be a big hit and give them all the clout they would need to make a proper big screen version of the beloved 1978 novel.

Sadly, Romero and King never did actually get to make their adaptation of The Stand, but fans can still be eternally grateful that they did manage to produce a true-blue classic together as their first collaboration. Written by the author himself (his first screenplay) and weaving together five diverse horror stories between bookends starring Tom Atkins and a young Joe Hill, Creepshow arrived in theaters in 1982, and became a box office hit.

Of those five stories, three of them were invented for the screen, but two of them Stephen King adapted from his own work. The second chapter in the anthology, titled “The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill,” is based on the short story “Weeds,” first published in the May 1976 issue of Cavalier magazine; and the fourth, “The Crate,” comes from the short with the same title that initially appeared in the July 1979 issue of Gallery. Given King’s direct involvement, clearly the faithfulness to the material isn’t a question here, but how do the original stories compare to what’s featured in Creepshow? And how has the movie held up in the decades since it was released? That’s what I’m diving into with this week’s Adapting Stephen King column.

What Creepshow Is About

As Stephen King expresses in his non-fiction book Danse Macabre, the author first “cut [his] teeth on William M. Gaines’s horror comics.” In the 1940s and 1950s, Gaines operated as the head of Entertaining Comics (a.k.a. EC Comics), and published popular/notorious tales of terror in series like Tales From The Crypt, The Vault Of Horror and The Haunt Of Fear. Reading the various books inspired a deep and unending love for the genre in the impressionable youth, and ultimately he channeled that passion into an incredible career writing stories that very well could have played out in the pages of those magazines.

Less than a decade after the release of his first novel, King had the opportunity to demonstrate his gratitude for the inspiration through Creepshow. The movie’s structure and general premise was designed as homage to the great EC Comics, and each of the tales told are akin to ones that were told in the publisher’s books. While obviously written as short stories, “Weeds” and “The Crate” both very much fit the bill in terms of their content and pacing.

Weeds/The Lonesome Death Of Jordy Verrill

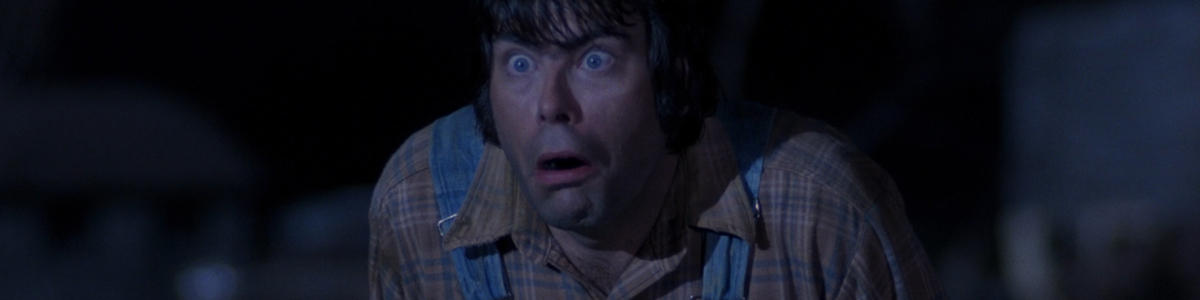

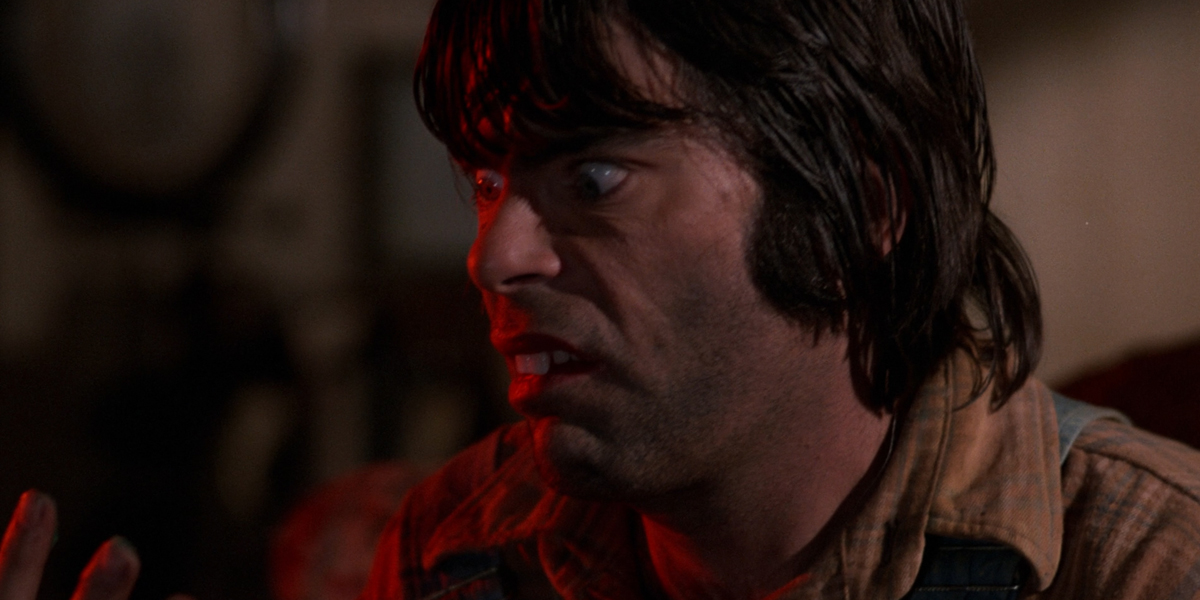

Stephen King made his on-camera debut in George A. Romero’s 1981 film Knightriders, appearing briefly in a scene alongside his wife Tabitha King, and “The Lonesome Death Of Jordy Verrill” in Creepshow provided the author his second opportunity to do a bit of performing, playing the segment’s titular bumpkin. Jordy is a farmer with little intelligence and the same amount of luck – though he initially thinks that he has struck paydirt when a meteor comes crashing down on his land.

Investigating the site, Jordy throws caution to the wind by trying to reach out and touch the space rock, but he burns his fingers when he does. He attempts to cool it down by dousing it with a bucket of water, but is disheartened when he sees that doing so splits the thing in half – revealing some kind of strange liquid inside (a.k.a. “meteor shit”). The lunkhead farmer is disappointed, but hopes that he can still get some money for the discovery.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

Unfortunately, he doesn’t live long enough to see that plan come to fruition. When Jordy settles in for a night of drinking and TV watching, he is distraught to discover that he has been infected with some kind of alien moss. The plant life continues to grow and grow, and the protagonist only exacerbates his problem when he jumps in the tub to relieve all the itching.

His home and his body overtaken by the extraterrestrial flora, Jordy wakes the next morning and understands that suicide via shotgun is his only option – though his life won’t be the only one taken, as the aggressive foliage continues to spread far beyond his residence.

The Crate

Contrasting the loneliness of Jordy Verrill, “The Crate” is arguably a story of friendship – specifically between Horlicks University Professors Dexter Stanley and Henry Northrup. It begins when a janitor approaches the former about a mysterious crate from 1834 discovered under a staircase in the zoology department. When Dex helps to pull the box out and open it, they are horrified to discover that there is a monstrous beast living inside, and the custodian gets pulled in and devoured. Desperate for help, the professor finds one of his graduate students in the hall, but the kid winds up meeting an equally gruesome death.

Terrified and not knowing what else to do, Dexter goes to Henry’s house and tells him the whole story. But while the shaken teacher expects that he will either horrify his friend, or just appear totally insane, Henry instead has an unexpected reaction – seeing the discovered crate as an opportunity to get rid of his horrible wife, Wilma (Adrienne Barbeau).

How George A. Romero’s Creepshow Differs From Stephen King’s Weeds And The Crate

No work is guaranteed to be free of changes when transferring to a new medium, and that includes instances when the original author is holding the pen for the adaptation. Stephen King’s “Weeds” and “The Crate” are basically the same stories that are presented in Creepshow, though there are some noteworthy differences.

Weeds/The Lonesome Death Of Jordy Verrill

Adapting “Weeds” for Creepshow, Stephen King, George A. Romero, and the filmmakers involved with the production made some minor aesthetic changes – such as having the meteor shit look like blue goo instead of oatmeal, having the first moss appear on Jordy’s fingers and tongue instead of his eyeball; and Jordy having a vision of his father in the mirror. The biggest alteration is in the ending, however, and it’s not hard to see why when you think about it.

For starters, Stephen King is a touch meaner to poor Jordy in the short story, as his first attempt to blow his own head off is unsuccessful due to his shotgun not being loaded. He ultimately does commit suicide, but that’s only because of the other significant change in the conclusion: the perspective of the alien moss. As we learn from the writing’s third person perspective, the vicious plant operates with a hive mind and a constant hunger, and it actually retrieves shells for the firearm because it expresses curiosity that Jordy might taste better post-suicide. Reading the farmer’s mind by leaching into his brain, it also learns that there are more people to feed on in the next town, inspiring its further expansion.

The Crate

What primarily separates “The Crate” from its source material is less about details and more about structure (though it is also worth recognizing that the monster as initially written whistles like a teakettle when it is both about to attack and after it has eaten – something that is nixed in the movie). While Creepshow has events play out linearly, Stephen King’s original work is more built around Dexter Stanley (Fritz Weaver) and Henry Northrup (Hal Holbrook) sharing accounts of their horrifying experiences. The short story begins with Dex arriving at Henry’s house to tell him about the attack on the janitor and his graduate student; and then after Dex wakes up after being drugged, Henry tells him about how he set his wife up to be killed.

There is an argument to be made that the original version is a touch more positive too. While Dex remains hesitant to the end in the Creepshow adaptation, the final moments seeing him fretting about the monster escaping the crate (before it actually does), Stephen King’s story ends with a more relaxed attitude – with Dex excited that he could start playing chess with Henry as many as three times a week, and agreeing to accompany his pal to report Wilma missing (“What are friends for?”)

Is It Worthy Of The King?

As alluded to earlier in regards to The Stand, one of the most significant hurdles any Stephen King adaptation has to deal with is scale. Sometimes the novels are so expansive that a single feature film struggles to capture everything that makes the source material magical; and there is also a significant history of filmmakers having trouble expanding on the author’s short stories and novellas to hit a certain runtime. As an anthology film, however, Creepshow has a way to circumvent the latter, and what culminates is a delightful and clever collection that is both funny and horrifying in equal measure.

“The Lonesome Death Of Jordy Verrill” and “The Crate” are two of the best chapters in the movie – one throwing an appreciated dose of dark comedy in the mix, and the other contributing some wonderful gore – but really every story has its own special touch that benefits the whole experience. George A. Romero, who first met Stephen King when there were talks of him adapting Salem’s Lot, spectacularly executes the vision of Creepshow as a comic book come to life, with perfect framing and editing that mirrors the experience of flipping through panels and pages while under your covers with a flashlight.

No discussion of Creepshow would be complete without also mentioning the genius work of make-up artist/actor Tom Savini, who worked side-by-side with George A. Romero throughout the entirety of his career, and did some of his best effects work ever in the making of the 1982 anthology feature. From terrifying moss, to a horrible ape creature, to monstrous zombies (both out-of-the-grave and out-of-the-sea types), it’s stunning and magical special effects work.

It’s clearly a very different kind of Stephen King movie than those I’ve previously dug into with this column, and one that the author personally had a much bigger hand in making, but all things considered Creepshow is regardless a highlight in the filmography.

How To Watch George A. Romero’s Creepshow

While it has been previously available on Shudder (which has an original anthology series based on the movie), George A. Romero’s Creepshow is sadly not currently streaming on any services presently. That being said, it’s not at all hard to find it. The movie is available to rent and/or purchase digitally from all major platforms – and if you’re a big fan you truly cannot do any better than the Collector’s Edition Blu-ray released by Scream Factory, which features a beautifully restored version of the film, a ton of special features, and a great essay by Michael Gingold (who deserves a hat tip for the background information in the intro of this feature).

Continuing to move through the years, the next installment of this column will be our first visit to Castle Rock, Maine and the spectacularly dark tussle with the most infamous dog in cinema history. Lewis Teague's Cujo is on deck, so be on the lookout for that piece, as well as more of my Stephen King coverage here on CinemaBlend. For now, explore previous installments of Adapting Stephen King by clicking through the banners below!

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.