People who view screenwriting as an art and don't particularly care about audience reaction to their films bristle at the thought of screenplay classes, in which Plot Element A and Plot Element B can be put together in such a way that-- voila!-- a hit is born. But Roland Emmerich has taken that very kind of formula writing and made a veritable empire out of it, returning every few years to destroy some corner of the earth and invent a handful of earnest heroes, wisecracking sidekicks and solemn old men to survive his newest take on the apocalypse.

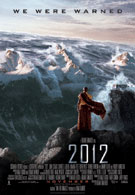

With 2012, as you probably could have guessed from the poster art of tidal waves crashing over the Himalayas, Emmerich is letting go of whatever restraint he might have had before. Clocking in at nearly three hours, boasting about a dozen major characters and at least half a dozen emotional death scenes, 2012 operates on the assumption that, if we liked seeing New York destroyed in The Day After Tomorrow and Washington D.C. zapped in Independence Day, we'll really love witnessing the wholesale destruction of the globe.

I hate to say it, but Emmerich is pretty much right. Far from conveying the horrors that might befall us should anything remotely so destructive happen, 2012 feels more like a soothing bath of Hollywood tropes and cliches, allowing us to witness Los Angeles slide into the ocean like Atlantis, but then warming us with a Woody Harrelson wisecrack and a rousing speech from Chiwetel Ejiofor. It's numbing, sure, especially when the first half is nothing but CGI explosion after another, but on some level it's exactly what we expect out of Hollywood-- shallow spectacle and a bevy of stars, an adventure and a few moral lessons, a giant budget spent guaranteeing we won't feel a bit different than we did when walking into the theater.

If there's any surprise at all in 2012, it's that Chiwetel Ejiofor, not John Cusack, is in fact the star of the film. We meet him in what amount to the film's prologue, a White House-employed geologist trying to prove to a cynical chief of staff (Oliver Platt, wonderfully hammy and villainous) that, in fact, the end is nigh. The cause is less important than the results-- giant fissures open up in the earth's surface, mountains turns to volcanos and skyscrapers turn to ash, and eventually tidal waves cover the entire earth's surface.

Billions of people die in the ensuing melee, but there are only a few we're instructed to care about. Chief among them is Cusack and his family, who start driving out of Los Angeles seconds before the destruction begins thanks to a tip from Woody Harrelson, who plays a Yellowstone-residing conspiracy theorist who saw the whole thing coming and made a YouTube video about it (Emmerich's nods toward modern concerns, like casting Danny Glover as the President and having characters constantly complain about cell service, head toward parody when Harrelson demands that Cusack "download my blog.") Plot mechanics too silly to describe require Cusack, his ex-wife (Amanda Peet), her new boyfriend (Tom McCarthy) and their cutesy kids (Liam James and Morgan Lily) to fly a series of planes on their way to China, where they intend to save their own skins in a manner that's best left discovered in the theater.

Somewhere along the way George Segal perishes on a cruise ship, Danny Glover does the heroic Presidential thing, a Russian oligarch and his bratty kids team up with Cusack and company, and the main players in Washington-- plus the President's comely daughter (Thandie Newton)-- all make their way to a souped-up version of Dick Cheney's undisclosed location. The final quarter of the film, while utterly unnecessary to the disaster elements, is also the best section, finally abandoning generic and plasticine CGI for situations that feel real and dangerous. There's no villain here, unless you count the merely loathsome Platt character, so it takes a lot of effort to keep putting the characters in danger, and by the end of the movie, Emmerich has most certainly run out ideas. But there's something about the scale of it all, or maybe the way seemingly random characters tie into the main plot, that keeps the train chugging along. When Ejiofor gets to make his hero speech, and certain bad characters make good at the eleventh hour, it's not quite a "This is our Independence Day!" moment, but it does come closer than any of Emmerich's films since then. Somehow he's got a real heart beating inside his movie, and no amount of groaner one-liners or thunderous explosions can take that away.

Emmerich claims that 2012 is his final disaster movie, unless Independence Day 2 ever gets off the ground, and the movie is nothing if not an indulgent curtain call for the man who figured out how much we like watching cinematic portrayals of our own demise. It's all the reasons we've ever loved or hated his movies, but also a reminder of why it's high time to move on. When he ends the movie, no lie, on a bathroom, joke, it's not exactly going out on top, but those of us who love Emmerich despite him wouldn't have wanted it any other way.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend