Soul wants you to stop and think about how you are living your life. How many movies aspire to that ambitious ask? Very few. Even less succeed in making you do so. That’s part of what makes this animated masterpiece so special. Director Pete Docter has been warming up for this type of thorough, invasive, spirit-testing, head-to-toe self-examination of our time spent on this floating rock. Think about some of the small (but pivotal) questions he snuck into his previous Pixar adventures. Could Carl, the protagonist in Up, accept a life with his soulmate, Ellie? Would Inside Out’s Riley ever get comfortable in her family’s new home city? If we aren’t wrestling with these issues, we overlook them. The magic of Doctor is that he understands how enormous the problems can be.

Soul is his biggest swing yet, and he connects with full force on every level. The beautiful, spiritual, amusing, inspiring and life-affirming ode to our pursuit of purpose introduces two incredibly memorable Pixar leads from wildly different realms, and sets them on a course that will, again, cause you to pause and think about what you have done in life, what else you want to do, and whether you are making the right choices to get there. It’s vintage Pixar, and is guaranteed to be one of this year’s greatest films.

Soul takes us someplace truly remarkable: The afterlife.

We have seen death in Pixar films before. I mentioned Pete Docter’s Up, and the opening montage is a heartbreaking ode to a love, and a life, lived to its fullest. Soul is different. The central story of Soul really can’t begin until the main character, middle-school band instructor Joe Gardner (Jamie Foxx), dies.

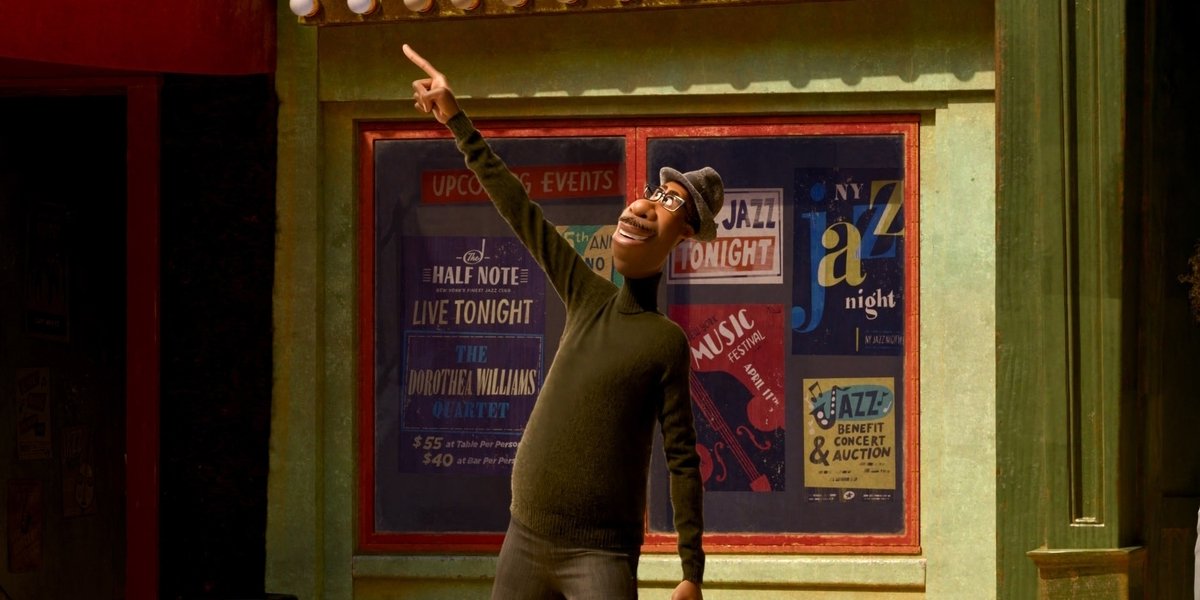

It’s dark, but it’s essential. Joe dies on the day that the struggling jazz musician finally gets his first real break at a genuine gig. He “wakes up” as a soul in The Great Unknown, and then tries to move Heaven in order to somehow get back to Earth. It’s a terrific concept, and one that frees Docter and his animation team to playfully create anything they want in the ethereal afterlife. The rules fly by Joe (and us) at a rapid clip. Souls in limbo have no senses, so pizza slices have no taste or smell. (Sounds like Hell.) Pirate-inspired souls congregate in the corners of the afterlife, even though they are still attached to bodies. Their human forms can “zone out,” a concept Joe explores through music in Soul’s most breathtaking scene.

And Joe receives a mission. He has to be a mentor. And Pixar gives us one of its greatest characters ever in 22 (Tina Fey).

Soul’s two main characters are flawed, fascinating studies.

After personifying emotions in the illuminating Inside Out, Pete Docter figures out how to present a soul, introducing the concept of souls in a realm called The Great Before. It’s genius. Here, souls are prepared to be sent to Earth once they figure out the one thing that makes them special, or gives them purpose. Joe immediately assumes that his “purpose” involves music. Before he can prove that, he’s tasked with helping a lost soul named 22 (Fey), who never figured out her calling despite help from a litany of famous, deceased mentors.

It’s a familiar trope: Two characters with complications who must work together to solve their problems and achieve their stated goals. But it’s the weight of the issues plaguing Joe and 22 that elevate Soul to levels not yet achieved by Pixar. This is metaphysical, soul-searching material that will reach deep into our own identities and turn a mirror back on us, forcing us to reflect. 22, for example, not only can’t find her “spark” (the thing that gives her purpose), she’s addled with the negativity that comes from mentors telling her she’s not good enough, and she’ll never be good enough. Joe, meanwhile, has been chasing a dream, sacrificing basically everything else in his life to attain it. But what if his dream is wrong, and the goal he’s been chasing isn’t really the right one? When do you stop chasing? When is it the right time to pivot?

There are no easy answers to these questions, and Soul has few solutions to the massive questions it raises. But you appreciate the journey both of the main characters take, and understand the detours they follow to reach their conclusions. 22, in particular, is one of the most rewarding characters in Pixar’s stable, an inimitable sprite who’s tough to peg because she’s aloof, misguided, indifferent but desperately in need of guidance. Watching her evolve has been the most entertaining parts of my Soul rewatches.

Pixar made Soul for parents.

The verdict leveled at most Pixar movies is that they are made for kids, but there’s plenty of material – both humorous and intelligent – to appeal to the parents in the audience. Soul, on the other hand, seems like it’s destined to fly so far over the heads of adolescent audience members that I’m certain the movie wasn’t made for them.

That’s not to say there isn’t a wealth of visual artistry and humorous physical comedy at play in Soul. Kids will be entertained. But they can’t possibly understand the existential crossroads both Joe and 22 stand at, with each wondering if they’ve lived wasted lives, or if they’ve placed importance on the wrong aspects of living. These are lessons that only a person who’s actually lived can best appreciate, so at least they will be there, waiting for younger audiences as they grow and learn what Docter has achieved here.

Soul pours out of the heart and mind of a creator who has spent ample amounts of time contemplating the value of the day to day, and minute to minute, moments that make up existence. I appreciate how much this film helps me to appreciate those beats more, because of it.

Sean O’Connell is a journalist and CinemaBlend’s Managing Editor. Having been with the site since 2011, Sean interviewed myriad directors, actors and producers, and created ReelBlend, which he proudly cohosts with Jake Hamilton and Kevin McCarthy. And he's the author of RELEASE THE SNYDER CUT, the Spider-Man history book WITH GREAT POWER, and an upcoming book about Bruce Willis.