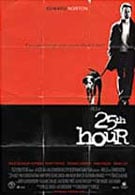

25th Hour follows the final day of a convicted drug supplier soon headed to prison for seven years. The first time we see Monty Brogan (Edward Norton) he’s rescuing a dog that’s been half beaten to death. He hangs around with bad people, Russian Mafia, killers, and murderers though he himself has apparently never fired a gun. Monty’s a likable guy, thoughtful, kind-hearted, and regretful of the greed, if not the crime, which led him to this final day. Now he has 24 hours to say goodbye, to make peace with his family, his friends, and his dog.

Brogan is a real New York City player, striding urban sprawl amongst the elite and powerful, he uses his money to help his father (Brian Cox), support his girlfriend, and build for himself a perfect lifestyle. These same people know what Monty does and know what he is, though they accept his money without stepping forward to tell him that maybe he should stop. Yet, his family and his friends are loyal, and on this, what is in effect his last day, they, along with him come to grips with the road he has taken and their roles in it.

In this is a film filled with scenes of lasting and permanent impression. Director Spike Lee bravely treads into the imagery of 9/11 right from the start, opening with a shot of a New York City’s nighttime cityscape, as two beams of pure white light shoot into the heavens where the World Trade Center should have been. Lee uses this not to remind us of tragedy, but to set a tone for an entire movie grounded firmly in the reality of today’s post-9/11 New York.

New York itself is a vibrant and daring player in the film, with 25th Hour’s characters firmly entrenched as part of that great city. For instance there’s Monty’s friend Frank: A stockbroker living in a high priced apartment overlooking where the World Trade Center once stood. Overlooking that horrific scene of emptiness, he and Jakob, the only real friends remaining in Monty’s life argue about whether there is any future for Monty. Their conclusion is as bleak and empty as the wasteland stretching beneath Frank’s window.

Brogan’s friends’ story runs in parallel to his own, with each intersecting with him and intertwining their own lives with his on this final day. Jakob (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is a teacher in a dead end position as some sort of penance for guilt he feels over being born into money. He’s quiet and unassuming, lacking in social skills or other graces. He obsesses over his beautiful 17 year-old student Mary (Anna Paquin), but tries desperately to repress feelings that he knows are so horribly wrong. Spying him from across the street as he enters Brogan’s trendy going away party, she confronts him and somehow manages to get him to let her in. Full of sexuality and vigor, Hoffman in yet another brilliant turn takes Jakob to the brink as he is forced to come to grips with his own inadequacy, and eventually makes a choice that will likely impact them both he and Mary forever.

Frank (Barry Pepper) on the other hand is driven and successful, a powerhouse on Wall Street who refuses to give up his Ground Zero apartment even though some question whether or not it is safe. Yet he’s wracked with guilt over what Monty has become. He questions why he never told him to stop. His anger at himself pours out at others around Monty who’ve accepted his money and in Frank’s eyes, encouraged him down the dead end path he’s taken. Pepper really draws out something unexpected in Frank and delightfully exceeds the types of limited acting I thought he was capable of. Honestly, both Pepper and Rosario Dawson, as Brogan’s girlfriend Naturalle, may have delivered the two best performances of their fairly spotty careers. For once Dawson adds something to a film instead of doing her part to suck the life out of it and Pepper is light-years beyond the painful acting that earned him so many jeers in Travolta’s Battlefield Earth.

But Monty is this film’s center, his anger and frustration at his life and the world around him pervading every aspect of Lee’s movie. Norton is brilliant in creating a sympathetic and likable character that honestly feels little real remorse. At one point his intense anger barrels to the surface, in a massive tirade against New York and every person in it said with energy and pain to Brogan’s mirrored reflection. “Fuck you all,” says Monty Brogan, in a speech bound to piss off every group to tread America’s streets. But at the end of his outpouring of disillusionment, he reaches the real problem by closing with “No, fuck you Montgomery Brogan. Fuck you.” Norton and Lee make a perfect team snuggled warmly inside a tight and deeply constructed script. In their hands, 25th Hour is not so much a movie about redemption, but a movie about facing the choices you’ve made in one life stage, and treading into a new one. 25th Hour never really tells us where Monty Brogan’s final day ends, whether he goes to prison or chooses to run. It stops when this phase in Brogan’s world does, leaving that choice and the consequences of it as a part of something else.

Some might find the pacing too deliberate, but the focus here is on dialogue and character. The result is a compelling and thoughtful film that puts a new spin on the types of choices we’re all faced to make. As Monty Brogan faces his future and his blasted past, we’re left ultimately to face our own choices as Brogan will, alone.