Being John Malkovich, Director Spike Jonze’s inventive and offbeat tale, was about entering the mind of one of the most curious actors working today. When it was released in 1999, audiences and critics agreed that it was one of the cleverest films of the year. I was among them. As much as I enjoyed the film, I felt that the level of praise was taken too far. It was fresh, no doubt, but hardly on my “Top 10” list of the year. However, Adaptation will be.

At the beginning, we hear a voiceover. The person speaking...we don’t know. He is not telling us his story, nor any other story for that matter. He is just talking to himself, looking over his endless compilation of human flaws. He is not a happy man. We’re eavesdropping, and we can’t stop listening. Our narrator stops. We flash back to 1998. The viewer is put on the set of Being John Malkovich, listening to the title actor give some helpful hints to the crew as he sits at a dining table wearing an evening dress. Cowering in the corner is Charlie Kaufman (Nicholas Cage), the overweight, balding, sexually-frustrated writer of the film. We always knew that it took a twisted mind to concoct that story. Now, we meet the man who owns the mind. No one knows him. No one speaks to him. And he gives them no reason to. He is the reason why everyone is there. He is their creator. They don’t even know it.

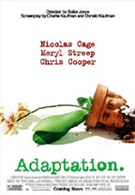

Fast forward three years: Kaufman is the same miserable sourpuss. He makes his indifference to change very clear when he is asked to adapt “The Orchid Thief,” a new novel by Susan Orlean (Meryl Streep), about noted flower hunter John Laroche (Chris Cooper) in his quest for a holy flower known as the “ghost.” He tells the studio woman who is pitching (a word deeply despised by Kaufman) the idea that he wishes to avoid telling a story about growing, “coming to terms with things,” or overcoming obstacles. He wants to tell a story about the opposition to change. This is what Charlie Kaufman is all about: resisting change.

Kaufman is faced with many problems. He has never adapted a published work for the screen. He feels that there is nothing at the core of this story. As a result, he is unable to adapt it. His ambition is sprawling, but his execution is nearly nonexistent. He is aided by his sinfully oblivious twin brother, Donald (also Cage), who regards him as a genius, and turns to him when he decides to develop a screenplay of his own, one which he describes as The Silence of The Lambs meets Psycho.

To describe the film further would be to detract from the inspired insanity that is Adaptation. Thankfully, the film never mistakes inanity for insanity. Every gleefully wacko moment seems carefully thought out. The viewer begins to believe that this film might have started out as a film adaptation of “The Orchid Thief,” to be written by the real life Charlie Kaufman, but soon developed into this inventively twisted, often ingenious tale. As it happens, it actually did.

Adaptation creates an alternate universe of sorts, much as Kevin Smith did with films like Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, in which actors like Ben Affleck play a certain character in one scene, only to play themselves later on. In this film, we have actors like John Malkovich and John Cusack playing themselves, yet Cage, their Con Air costar is no longer himself. The view is warped yet entrancing, becoming a circular puzzle where conventional methods of understanding the story become enjoyable tasks on their own.

When he switched gears from playing the diabolical Castor Troy to the virtuous Sean Archer in the action classic Face/Off, he gave a glimpse of how well he could pull off dual roles. Cage plays Charlie as an unmitigated mess at one moment and the cooler, confident Donald in the next. His performance is sheer brilliance, sure to be remembered come Oscar time. Adaptation is also a welcome note for fans of Cage (like me) who have been disappointed to see such a gifted actor dedicating himself solely to glossy action-thrillers and old-fashioned war stories for the past few years. He returns to the roots of his vividly bizarre work in films like Raising Arizona and Leaving Las Vegas.

Compared to Barton Fink, the Coen Brother’s typically bizarre tale about a Manhattan intellectual who goes Hollywood, Adaptation is perhaps the best film ever made to chronicle the oppressive screenwriting process. Kaufman’s gradual loss of focus and resulting desperation is something that anyone who has ever attempted to put something down on paper and met a certain amount of difficulty could connect to.

The film takes a somewhat different form near the end when Kaufman encounters Orlean and Laroche. The only issue I had with this this new passage was that it was much less engrossing. The power of his frustration and pain is disposed of in favor of a more linear film. Then again, that might have been the point. Charlie refuses to change his personality and his methods of writing, only to become part of a mediocre plotline and transform as a result.

You can see the direction Spike Jonze is taking with his body of work. His two directorial efforts are part of a whole that exist together yet are separate for telling such different stories. I can not begin to imagine what he has up his sleeve. Perhaps he will next chronicle his effort to direct Adaptation.