We live in an age of unprecedented concern about our food, in which the food pyramid is constantly revamped, local greens are fetishized to an almost religious degree, and the First Family is tending an organic garden on their lawn. Despite booming profits at McDonald's and pervasive ads for junk food aimed at children, it seems like everyone knows about the dangers of high-fructose corn syrup, grain-fed beef and non-organic milk.

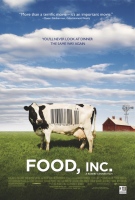

Obviously this isn't true. But if you know all this already, you might find Food Inc. to be a bit of a rehash, a well-executed mash-up of Fast Food Nation and The Omnivore's Dilemma that restates the argument that the industrial food system is, in effect, killing us. There are some benefits to the cinematic approach, from the striking graphs and charts to the vibrant presence of interviewees who weren't captured nearly so well on the page. And it's clear that director Robert Kenner shares the same passion for real food that Fast Food Nation author Eric Schlosser and Omnivore author Michael Pollan touted in their books, to the point that Food Inc. sits comfortably next to those revered tomes. But if you've got them both on your bookshelf, don't feel surprised if you come out of Food Inc. feeling like you've learned nothing new.

To his credit Kenner builds an entertaining and swift film out of his complex argument, which spans from a woman whose toddler died from eating e. coli-tainted beef to Joel Salatin, a colorful, deeply devoted Virginia farmer whose organic chicken and beef inspires customers to make four-hour drives to his Shenandoah Valley farm. But Kenner starts things off where Pollan did in his book: corn. Modified by scientists, morphed into every foodstuff imaginable and even fed to cows, who are by nature grass-eaters, corn has become the backbone of a food system that treats crops as a manufactured product, not a natural phenomenon. Kenner neatly sums it all up using a striking visual metaphor: a meat substitute meant to kill the e. coli found in the stomachs of cows fed only corn (but not those fed grass), made of corn and boxed in perfectly square, perfectly white blobs. Yes, that's what we call food.

Kenner also one-ups Pollan, and continues the work done by Schlosser, by examining the human toll of this ridiculous system. There are the chicken farmers kept in permanent debt by companies like Tyson and Purdue, who pick up the ill and poorly kept chickens to be pressed into nuggets and other unrecognizable foodstuffs. And there are also everyday families like the California foursome who are forced to spend less on groceries-- therefore buying fewer fresh foods and more junk-- in order to pay for the father's diabetes medicine. None are as heartbreaking, though, as Barbara Kowalcyk, the mother who lost her toddler son after feeding him a store-bought hamburger that turned out to be infected with e. coli. Her plight is as strong a wake-up call as any, a reminder that while some of us can live with the state of our food, others are dying as a result of it.

Not quite a true polemic, and building slowly to its heady steam of outrage, Food Inc. is a call to arms that slips into you slowly, until at the end you're convinced you'll never eat another french fry that you didn't see cooked with your own eyes. It's the same effect that Fast Food Nation, Omnivore's Dilemma and other books and articles have had on millions of readers, but if Food Inc. can help spread the message that our food system needs serious overhaul, then more power to it. Success stories, like Stonyfield Farms' successful inclusion of organic dairy at Wal-Mart, indicates that individual consumers can make a difference. Maybe individual moviegoers buying tickets for this-- and eschewing popcorn, naturally-- will be another small step in the right direction.

TRAILER:

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend