It’s been described as the most important game in college basketball history. The 1966 NCAA championship isn’t noteworthy for anything that happened in the competition, but rather for who played in it. Hard though it may be to believe looking at today’s teams, back in 1966 black players didn’t play college basketball. One coach, Don Haskins, decided to change that. Initially it wasn’t because he wanted to right a wrong or fight an unjust oppression, but because he wanted to win and couldn’t get anyone else.

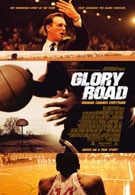

Glory Road tells the story of Don Haskins (Josh Lucas) and his 1966 Texas Western basketball team, the first college team ever to use a starting lineup composed entirely of black players. Texas Western was a poor school, and Haskins took the job as his only way to transition from coaching girl’s high school basketball into division one NCAA. The school hired him not because they were interested in winning, but because they wanted a strong male presence to move into their men’s dorm and lay down the law. Haskins had loftier plans.

His plans included, among other things, moving his wife and kids into the men’s dorm with him, and then ignoring them until he needed someone to underscore the danger in flaunting hillbilly west Texas’s lily-white traditions. At least that’s the way Glory Road presents it.

Haskins soon realizes he has nothing to work with. The school won’t give him money for recruiting and he’s stuck in El Paso, where no one in their right mind would want to live, let alone play. Determined to win, he starts thinking outside the box, and notices black players being shunned by the bigger schools, regardless of their talent. Seeing an opening, he starts recruiting from inner-city street-ballers, bringing seven black players to Texas Western to play for him. His recruiting pitch? “I don’t see color, I just see talent.” Vowing to his new student athletes that on his team they’ll start rather than ride the bench as token black men, he turns his tiny school’s basketball program around. Suddenly they’ve gone from last place poverty to contending for the NCAA championship.

But the Don Haskins presented in Glory Road is a hypocrite and the movie misses opportunities to achieve something good with an undeniably great story. It’s hard not to compare it to another Disney sports movie on a similar subject, Remember the Titans, the story of an African American coach integrating high school football. Remember the Titans is a masterful piece of work, one which focuses on the character conflict between students and teammates trying to deal with being forced to work together. The world around them spits on them, but they use that to draw closer together. In Glory Road there’s none of that. There’s a clear division between the white players and the black players on Haskin’s team, with his black players painted as borderline hate-mongering racists and his white players relegated to patsies there to step out of the way while history marches on by them.

Neither Haskins nor any of his team is really well developed. The players are never fleshed out much beyond their court presence. You’ll find yourself thinking of them as the white kid with glasses or the black short kid. There’s some attempt to make a few of them more prominent, but it never happens and it’s half-hearted. Haskins himself is little more than a two-dimensional figure who stalks back and forth shouting orders. He makes grandiose speeches about how he isn’t here to make a social statement; he just wants to play good basketball. “I don’t see color!” he exclaims before intentionally benching all of his white players in the final game of the year to make exactly the social statement he claims he wasn’t interested in making. He chooses to endanger the life of a black player with a heart condition, rather than allow one of his white players on the court.

If Haskins wanted to make a social statement, fighting discrimination by proving once and for all that black players could compete in college basketball, then I’m all for it. But don’t let him at the same time ply his team and the media with false platitudes that claim exactly the opposite. The Haskins in this movie did see color, and in the end knowingly chose to make exactly the social statement he said he wasn’t interested in, punishing his hard-working white players in the process. What are we supposed to think about that?

I refuse to believe this is actually the way it happened, and instead have to think that director James Gartner and screenwriter Chris Cleveland are simply off their rockers. There’s no subtly to this story, it’s blatantly obvious, grasping for all the easiest symbolism to drive its point home. When the movie tries for subtly, it’s usually only to infer something stupid. For instance Adolph Rupp (John Voight) is the coach of Texas Western’s big rival. Glory Road makes the baffling decision to try and portray him as a Nazi, without coming right out and saying it. Oh, there’s a brief scene where his wife says “not everyone feels that way” in defense of Haskin’s wife, and Rupp never says anything even remotely racist. But the massive, fascist looking banner sporting Rupp’s face that hangs from the top of his school’s gym is downright suspicious, as is an announcer’s obsessive predilection for calling Rupp “The Baron”. Alright, maybe that was really his nickname, but do you have to shout it while he’s standing in front of an audience full of confederate flags? Just because the guy’s name is Adolph doesn’t make him Hitler’s step-cousin.

In the end, I have no idea what Glory Road wanted to be, or what it’s trying to say if anything. As a sports movie it follows the same predictable formula they all do, but its subject matter is such that it could have and should have used that to lift itself beyond that basic formula. Remember the Titans did it, Glory Road could have too. Gartner never manages to balance the need to capture the explosive nature of the times in which Haskins is living, while letting us get to know and sympathize with his players on a personal level. Instead, what we’re left with is an awkward grab-bag of mixed messages and mediocre on-court footage. If you’re interested at all in what it was like to be part of this momentous event, stick around after the movie’s credits for interviews with the real players who were there breaking down barriers. The movie is a lame-duck, but watching those men speak about what they fought for is something special. The players and coaches of Texas Western changed the sport of basketball forever; Glory Road accomplishes nothing.

Chris Evans Pens Sweet Tribute To ‘Older Sibling’ Scarlett Johansson, And Now I Really Need To See Them Team Up For Another Movie

Bowen Yang And Kelly Marie Tran Open Up About Crew Members Sharing What It Felt To Work On A Queer Set For The Wedding Banquet: 'It Just Felt Really Magical.'