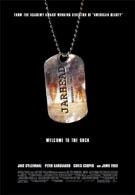

While technically a war movie, Jarhead is much more than that. It breaks barriers on just about every level as it deals with a platoon of snipers in the Marines. Nobody dies. Nobody kills. Nobody does much of anything. The horror of war, based on Tony Swofford’s memoir of his experiences in the Gulf War, is more in the waiting than the doing. This is not a typical war movie, unless men playing gas mask football in the desert of Saudi Arabia fits your definition.

Tony, known as “Swoff” (Jake Gyllenhaal) joined the Marines in 1988. He was on a quest for something fresh and exciting, and decided to become a Jarhead—a self-created nickname by the Marines influenced by their odd haircuts—instead of hitting the nearest university. When Swoff first meets the men in his platoon, Troy (Peter Sarsgaard) announces “Hey boys, fresh meat!” and they tie him to a bed and pretend to brand him with a marine logo. “Welcome to the suck!” they exclaim to the new recruit.

Together they all experience a grueling boot camp ordeal, led by Sergeant Sykes (Jamie Foxx). He loves the Marine Corps more than his own flesh and blood, and his hard-ass ways stem more from a love of the military than desire to bully. He is nothing like Full Metal Jacket’s R. Lee Ermey, who is cold and malicious just because he can be. Their training leads them to run marathon-style every day and endure tough physical regimens in the blistering heat. The song “Don’t worry, be happy” plays overhead because it’s just that kind of tongue-in-cheek flick.

Before long, the platoon of snipers gets sent to Saudi Arabia, expecting to be there for no more than a couple of weeks. Days turn into weeks and weeks turn into months in the middle of the Gulf War. Only there really isn’t much of a war going on, though they are forbidden from letting reporters know that tidbit. Essentially, they are a pack of frat boys spending time in the desert getting drunk, playing ball, making sexual comments, and fantasizing about their girlfriends back home. Tony is thrilled to be there, waiting for his chance to fight, until he realizes that his girlfriend is cheating on him back in the States. Suddenly he becomes aware that he is off at a war wasting time, while his life back home fades from his grasp.

To put it mildly, Tony goes a bit wacky. At a Christmas party, he dances around naked with a Santa hat on his head, and another one strategically placed elsewhere. A conflict causes him to put a gun to the chin of scared platoon mate Fergus (Brian Geraghty), and he seems to have no reservations about being killed. When strangers approach, he is first to step forward. In a scene where the men are hiding in a dugout hole dodging explosions (the only few minutes of combat they see), Tony stands proudly in front of it with sand blowing on his face. The line between bravery and insanity is paper thin.

Jarhead proves that war movies don’t have to follow the same generic formula to be effective. This a story about young men trying to find their way, and determining what battles are worth fighting. It’s surprisingly apolitical; there is no theme of ‘war is bad’ or ‘war is good’. The men are displeased with the war because they were trained to be fighters and that’s not what they’re doing. They want to kill, but are not given the chance, and that takes a curious toll on them.

The movie plays as a dark comedy with mildly dramatic undertones, keeping it light with a soundtrack full of great tunes from "The Doors" to "Nirvana". Sam Mendes should be commended for choosing his battles wisely, since Jarhead is only his second film since American Beauty. Many other directors would have turned the movie into something phony or false, but he keeps it honest and true to the book. It helps that his cast is magnificent, with further star making turns by Gyllenhaal and Sarsgaard.

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

The toughest challenge Jarhead may face is in finding the right audience. It won’t appeal to people seeking an action-packed bloodbath, and it will turn off moviegoers hoping for a feel-good film about heroic nationalism. This is a movie about friendship and coming of age. William Broyle’s witty script is full of humor and biting satire that never drowns in sentiment. Jarhead goes an unconventional route to show a side of war that movies often forget: the agony of waiting. Sometimes that can be even more grueling than the actual attack.