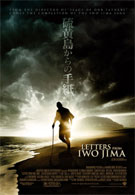

The second of Clint Eastwood’s two Iwo Jima themed movies, Letters from Iwo Jima retells the battle of Iwo Jima from the Japanese perspective. The first, Flags of our Fathers told the story as seen through American eyes. Letters from Iwo Jima does everything that Flags of our Fathers failed to do. In other words it actually tells the story of the fight, instead of getting bogged down in a war bonds marketing campaign back home.

It begins months before the United States’s invasion of the tiny Japanese island for which the movie is named, with Imperial troops fortifying and digging in. The war effort isn’t going well, and everyone knows Iwo Jima is a death trap. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi (Ken Watanabe) takes command of the Japanese forces stationed there, because everyone else refused the job. He arrives and insists on a walking tour of the island against his officer’s advice and immediately realizes they’ve got everything all wrong. Kuribayashi has traveled and studied in American, and knows how the Americans think. They can’t count on outside support, the Japanese military is in disarray, the navy has been defeated, and the Emperor is bringing all of their air assets home to prepare a last-ditch defense of the mainland, leaving Kuribayashi’s thousands of ground troops stranded alone on a blasted island, trapped like rats. He tears apart his commander’s defensive plans and makes them redo everything from scratch. He doesn’t make a lot of friends among the force’s weary warriors.

But they must not fall. Iwo Jima is the last line of defense before the Americans can attack the Japanese mainland. Kuribayashi sets his troops to digging in. By the time the Americans arrive to being their assault, the Japanese forces are hidden in a network of caves and tunnels throughout the island. The film quickly becomes a study in claustrophobia as Japanese troops futilely attempt to bear up under the unceasing waves of American attack. Kuribayashi must struggle against his own men’s code of honor, as soldiers schooled in the old way of honor fighting refuse to retreat, preferring suicide to tactical withdrawal. No one is allowed to die, says Kuribayashi, until he has killed ten enemy soldiers. They’re fighting a losing battle, they know they’re all dead, and in the midst of one of the most vicious, protracted pieces of war the world has ever seen, Letters tells individual stories of heroism as Japanese fighters prepare to die.

In doing so, the movie raises interesting questions about what courage is. Which is real bravery? The soldier who rushes heedlessly into battle to give his life in service to his country, or the man who refuses to die, so that he can make it back home to see his wife and daughter? Kuribayashi believes that a dead soldier is a useless soldier, and desperately tries to convince his troops to learn when to withdraw and survive another day. His commanders see only their old code of honor, and prefer death to the dishonor of defeat. In the end, none of it matters. They’re all dead, and they know it. Letters from Iwo Jima isn’t a movie about finding victory, but a lesson in what it really means to die with honor.

Iris Yamashita’s script is heartbreaking, capturing the broader strokes of what’s happening in the battle by focusing on the quiet internal struggle going on inside individuals in Kuribayashi’s doomed forces. The movie’s central character is a former young baker named Saigo (Kazunari Ninomiya), impressed into service by the Emperor and ripped away from his wife and unborn daughter to die on Iwo Jima’s distant shores. When everyone around him is looking for a way to die, he’s looking for a way to live, and the movie’s journey is really his as he escapes one route after another until he ends up with Kuribayashi right at the very end. All around him one comrade after another dies, some willingly, some go kicking and screaming. But Saigo scrambles on, dodging death, avoiding suspicions among his fellow troops, his only thought to find a way home to his baby and wife.

As Flags was, Letters is shot in washed out colors by Eastwood and Cinematographer Tom Stern, the only vibrancy coming from explosions, fire, and blood. The film is completely without glamour or glitz, yet in its bleakness is a kind of desperate beauty. This is as dire and moving war movie, the story of men being chewed up and spit out by forces beyond their control. It’s the film so many had hoped Flags of our Fathers would be and wasn’t. Eastwood finds more to say in defeat than he does in victory.