When Dustin Lance Black began writing a screenplay about Harvey Milk in 2004, Barack Obama was an unknown local politician, and the wave of state bans on gay marriages had only begun as ballot initiatives. And while Milk would be an excellent film any year, coming as it does in November 2008, it is almost unbearably poignant. A story about a politician who gave people hope, as well as his efforts to end prejudice against homosexuals in California, Milk is a loving bit of nostalgia for the blossoming gay rights movement of the 70s, but also a parable for our times.

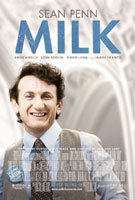

At the very top of the list of what makes Milk so exceptional is Sean Penn, who goes beyond even his usual dedication to give a chameleonic, utterly winning performance. It helps that Harvey Milk was apparently such an affable, magnetic guy, capable of picking up a longtime boyfriend with a proposition on a subway platform and attracting a cabal of young, energetic men when he opened a camera shop on San Francisco’s Castro Street in 1972. The neighborhood was already blossoming into a gay mecca, and despite protests from partner Scott Smith (James Franco, quiet and warm), Milk ventured into politics first by organizing local gay-friendly businesses, then by staging a series of failed runs for citywide office.

With the help of skilled political organizers like Cleve Jones (Emile Hirsch), capable of organizing crowds of thousands within an hour, and Anne Kronenberg (Alison Pill), Milk rallied the gay community against efforts in other cities to strip gay rights, even as his runs for office failed. On the strength of the politically organized community he created, Milk was elected as a San Francisco city supervisor, at the same time as conservative Catholic Dan White (Josh Brolin). As the first openly gay elected official in the country, Milk became an instant symbol for the gay rights movement—and a target for those threatened by it, White included.

Director Gus Van Sant effortlessly weaves archival material into the story, depicting the national scope of the gay rights movement while lending the entire film a nostalgic haze. He also employs a small amount of visual pizzazz, showing Milk’s campaign signs in bright close-ups and occasionally employing some haunting tracking shots. It all goes toward making Milk more than the usual biopic, immediate and touching rather than a dutiful recounting of life events.

Extra zing is added by the performances, none of which can match Penn’s titanic stature, but all of them playing off one another and fleshing out the rich San Francisco culture of the time. Hirsch and Pill lead the energetic band of Milk supporters with youthful charisma and spirit, while Franco tones it down to depict the personal tolls of a life lived in the public eye. Brolin is the standout, giving a nuanced, hugely sympathetic performance in a role that, in most other hands, would be pure villain.

Most importantly, Milk is a story felt deeply by all those involved in it, moving but unsentimental, fierce and intelligent and proud. It’s not the kind of “important message” film that should be force fed to the younguns, but a vibrant recreation of a fascinating time and place, and the singular man who helped create it.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend