The myth of the happy family pulling through times of joy and tragedy with equal aplomb often seems like a stereotype made up by Hollywood for the sheer value of making more films reiterating that point. What the Great Satan fails to recognize that there is no such thing as the happy family and, in any case, unhappiness is much more interesting. Rachel Getting Married gets it, reminding me of Tolstoy's prophetic line that all happy families are the same and all unhappy families are unhappy in their own way.

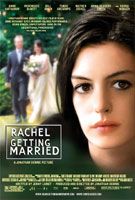

Despite the joyful occasion referred to in the title, the fractured Buchman family is deeply unhappy, and it shows. They are gathering for the marriage of eldest sister, Rachel (Rosmarie DeWitt), to musician Sidney (Tunde Adebimpe). Anne Hathaway plays younger sister Kym, a troubled woman who has been in and out of drug rehab since she was teenager. Though she’s been clean for 9 months and diligently attends support meetings, her troubles are apparent to everyone around her. When Kym walks into a convenience store near her home, the clerk asks her if she’s been on Cops. She returns to her family home with trepidation, clearly still atoning for the horrific tragedy her addiction has wreaked on the kin. Father Paul (Bill Irwin) meanwhile, doesn’t help matters with his incessant, overprotective worrying.

But whereas Kym feels as transparent as the cellophane on a package of cigarettes, Rachel, the older, more grounded sister feels invisible. Rachel has done everything correctly: gone to school, gotten a job, found a life partner and is about to marry him. But from the moment Kym walks through the front door the spotlight is diverted completely. Beneath the politely strained platitudes voiced by the siblings, it is apparent Rachel has been suffering in silence for years. Though she tries her hardest to be magnanimous, Rachel cannot understand why, after a lifetime playing by the rules, she has always flown under her father’s radar. The sisters’ divorced and remarried mother (Debra Winger) hangs around the edges of their lives in only the most tangential way, leaving the girls to navigate their murky relationship by themselves.

As the wedding approaches, the cracks in their family dynamic become ever more apparent. This slow unraveling is set against the rapidly approaching wedding, which is done in an Indian style - all vivid colors and shiny fabrics, with music wafting throughout the house at all hours of the day. Director Jonathan Demme says he took his cues primarily from Robert Altman, the master of controlled chaos. But Rachel Getting Married is more reminiscent The Celebration, the 1998 Dogme ’95 film directed by Thomas Vinterberg, than of the artfully controlled chaos of Altman. Like Rachel Getting Married, The Celebration is also about a dysfunctional family coming together for a large party and buckling under the mental strain of having to project happiness when happiness is the furthest thing from everybody’s mind. And like The Celebration,Rachel Getting Married makes use of the hand held camera as an extra member of the party, a ghostly guest roaming the halls of his haunted house, looking for answers in kitchen cabinets, in doorways, in an empty bedroom covered in child’s drawings.

Screenwriter Jenny Lumet has made a brave choice in not making her characters entirely sympathetic. By refusing to adhere to any typical conventions regarding relationships (such as unconditional love between siblings), larger truths are inferred by the audience. For all her flaws, Kym is not a bad person, just a selfish person as all addicts are selfish people. Rachel cannot abide by her sister’s need to take up space. Rachel then, too is selfish. But the kind of selfishness on display in Rachel Getting Married is the kind inherent to all families – the desire to spare each other pain by hiding their own pain until it is too late to do anything about it. There is great honesty in Lumet’s script and the light touch Demme brings to the material provides the perfect balance between pathos and humor (and yes, there are parts of Rachel Getting Married that are very funny indeed).

Aside from Demme and Lumet’s achievement, there are great performances all around, with special praise for Hathaway: she is a revelation playing against type. After a powerful scene in which Kym confronts her mother for failing to predict great sorrow, Anne shows us vividly the stages of misery: uncontrollable sobbing, heated rage, and mindless self-destruction, followed at last by the quiet contemplation that settles in after all the tears have fallen, what C.S. Lewis called the “feeling that nothing is ever going to happen again.”

Rachel Getting Married is the kind of film that’s sure to drum up lots of Oscar talk and wild predictions by critics. It may be deserved. But with or without awards hype, this little drama deserves to be seen by wider audiences.

Most Popular