Like virtually anyone my age with a passing interest in musical theater, I have a Rent story. I saw it in Greenville, South Carolina with friends from a summer arts program who had introduced me to the play in the first place. Greenville is home of Bob Jones University, where interracial dating is prohibited and homosexuality is out of the question, and my friends and I relished the notion that, mere miles away, we would see two men kiss onstage.

Since then I've loved the play not so much for its content, but for the nostalgia it represents, something shared by a group of fiercely loved friends. And even since I've moved to a New York very, very different from the one Jonathan Larson wrote about, Rent has served as a kind of token of entry among most people I've met. Everyone knows a reference to lighting the candle. Everyone knows why the East Village's Life Cafe is flooded with tourists.

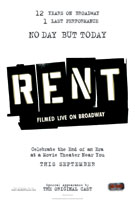

When Rent closed on Broadway a few weeks ago, after 12 years onstage, I can't say I was outraged. At this point, with million-dollar condos going up on Avenue B and most young, poor people shoved out of Manhattan entirely, Rent is as much a period piece as South Pacific or Les Miserables. Plus the songs were kind of cheesy, and the only people capable of being pulled in by the movie's young-artists-with-AIDS plight were tourists who had lost out on discount tickets to Mamma Mia!.

Then I was invited to an early screening of the new movie version of Rent, coming out this weekend through Sony's special events arm The Hot Ticket. Filmed during several live performances of the Broadway show, the movie version of Rent contains extreme close-ups and angles no theater audience could have seen-- you see everything from Maureen's butt when she moons Benny to the sweat on Angel's brow. The sound is perfect, the images are crisp-- all in all, it was way more than I saw from the upper balcony at the Peace Center back in Greenville.

And when the lights went up on Mark and his camera, I remembered all kinds of things I'd forgotten since I stopped listening to the soundtrack on repeat. Like the way the story looks square in the face of its characters' misery, despite the cheeky optimism that overtakes near the end. Or how funny and sarcastic it can be, especially in the character of Mark, who, played here by Adam Kantor, is more appealing than ever. Or how the fantasy of leaving everything behind and moving to Santa Fe, or anywhere, is still potent, even when the East Village has matured into a playground for wealthy college students.

I'm not afraid to admit I misted up during the "I'll Cover You" reprise, or when Mimi sang "Goodbye, Love." I heard plenty of sniffles in my audience as well. I imagine they were moved for the same reasons I was-- not just because of the story being told, but our own stories, the first time we heard that song and the person we saw the musical with, and any time we were in the East Village and secretly thought to ourselves, "Wow. This is where Rent was." No New Yorker will ever, ever admit to thinking that, but I guarantee it's more common than you think.

I'll never get to be 16 again, and listen to Rent and think of it as a secret window onto a place I could someday go. I'm jealous of the teenagers who have yet to see it, and are maybe anxiously awaiting Rent's arrival in their local movie theater. But it's also worth a visit for the rest of us, who have been there and done that but maybe have forgotten how good it feels. When, after the final curtain call, some of the original cast come onstage for a reprise of "Seasons of Love," you see some of them in tears, overwhelmed that the whole experience is over. It says a lot about the power of this remarkable play that we, the audience, feel a little of that emotion too.

You can find tickets to one of the four screenings of Rent here. The first screening is Wednesday, September 24.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend