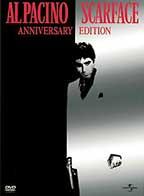

The remake of Scarface is a sprawling crime saga that follows the betrayal and loss that a single man endures; it is a coked-up version of The Godfather and The Godfather Part II without a family to feel sympathy for. So who better to carry the torch of crime into the decadent 1980s than Michael Corleone himself, Al Pacino? Pacino plays Tony Montana, a foul-mouthed and short-tempered Cuban refugee who, with the help of a fellow refugee (Steven Bauer), exits a dead-end life from the holding camps in Miami and his days as a pit-stop dishwasher to the universe of international drug empires. Through a big-time dealer (Robert Loggia) who sees promise in the newly emigrated Montana, he begins a rapid rise to power as a ruthless drug lord whose ego, paranoia, and lined up enemies threaten to end it all. During this rise, he ever-so-rudely woos the big boss’ moll (Michelle Pheiffer) and protects his baby sister (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) from any man who looks in her direction.

Scarface is told in three acts that detail Montana’s ascension into paradise, his stay in the heavens (mostly Miami), and his eventual descent from grace. At a whopping 170 minutes, the film never outstays its welcome because each act is told at a steady pace on its own. The opening act is deliberate so that the young Cuban’s future may feel even more uncertain. The middle act shows Montana reveling in his new way of life and taking the actions that could eventually lead to his downfall. The final act reaches moments of such absurdity it can only be purposeful. In an over-the-top scene clearly saved for the finale, Montana sniffs cocaine from a man-made mountain of the product on his desk. Because he lives a life of limitless excess, his character would naturally be taken into the stratosphere of the inane towards the climax. When you are this insane, the only place to go is up. Or down.

The view of this vast empire of drug dealings is no different than that of a carefully choreographed political picture. Every character is part of a web of lies and deceit who try to mask it with a wide smile and promise of a better tomorrow. At the same time that these promises are made, careful diversions are calculated by each character to advance themselves. This mirror of a political organization comes from screenwriter Oliver Stone, who treats these empires with the same respect as a legitimate government. No character is passed off as heroic, but several (primarily Montana) try to get across that they are not the only villains in the world. Their only problem is that they have trouble masking it in a world dominated by legitimate villains: politicians, bankers, etc.

Pacino, though, is the one whose excess brings Scarface to a different level of praise as an instant cult classic. With a lisp-y, jaw-protruded Cuban accent (that I have been told is not particularly accurate), Pacino renders even the most dramatic scenes practically laughable. His wildly over-the-top monstrosity is so hotheaded it could very well fuel a battle between The Academy and The Razzies. He creates a character that is a liar, but with morals. Conniving, but with a sense of loyalty. His traits contradict one another so frequently that it should come as no surprise to the viewer that Montana becomes his own worst enemy.

Aspects of the character feel like an amalgam of the young Vito Corleone and Pacino’s own Michael Corleone in the Godfather films. Like young Vito (played by Robert DeNiro in Godfather II), Montana is an immigrant who escapes the tyranny of his homeland to pursue his dreams in America. Though their motivations differ, they come to power very quickly. How they use that power parallels the younger Corleone and Tony. The viciousness here is uncontrolled and unhidden. Michael Corleone was a well-intentioned youth who was forced into a business to avenge an assassination attempt on his father. But as the business seduced him with its wealth of power, he grew obsessed with loyalty to his family and his actions (even against his own brother and sister) lead only to his solitude. As in the original Godfather, Tony takes a reluctant blonde along for the ride, and for his actions, his family (specifically, his younger sister) hate every bone in his greedy body. Scarface produces a story that can entrance you with its riches as it did to Tony. It should remind you that while crime doesn’t pay, it can still make you rich.