A Single Man follows a day in the life of a gay man living in 1962. George’s (Colin Firth) day starts with the decision to kill himself, after he awakens to the disappointment that he’s still breathing. We’re left to wonder whether he’ll still be breathing by the time his day’s over, but in the meantime George goes about the mundane trappings of his routine knowing that tonight he’ll finally receive the sweet release that only death can bring.

What’s surprising is that even though it’s set in the 60s, A Single Man avoids the standard examination of what it must have meant to be gay in an era of bigotry and social upheaval. Instead George lives a mostly normal life, a life in which many of the people around him seem to suspect the truth about his sexual orientation and may in fact, even secretly wish him well. George, however, sees none of that. Ripped apart by the grief and sadness which filled the hole in his heart after the sudden death of his long time companion Jim, he’s the loneliest man in the world.

George keeps going by focusing on the tiniest details of his existence and so too does director Tom Ford’s camera. The result is a lush and visually complex film in which the smallest moments of George’s day are shown in glorious detail. A smile from a secretary becomes a warm glow spreading across the entire screen as George, just for a second, lives in that one moment. It’s enough to get him from his car and into his office, where he soon returns to his world of grief.

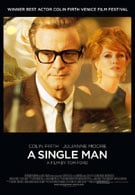

Colin Firth has never been better than he is here as George, an outwardly stoic figure, haunted by the memories of the man he loved and never said goodbye to. He goes through the motions of his day, struggling for some semblance of normalcy, but every now and then unable to keep the frustration of his life from leaking out. It’s a wrenching performance, a complete and complex character who leaves you with the feeling that in one day spent with him, we’ve only scratched the surface of who and what George is as a man. Still, he appears on screen fully formed, a mature person with a mysteriously wild past in London and a now ruined present where once upon a time, he loved someone. That he’s gay is almost ancillary, what matters most is that for awhile, George found true love.

Yet on paper it’s such a simple movie, that it might have been easy for A Single Man to dissolve into a mundane bore. Firth’s performance is brilliant, but Ford’s luxurious visual style and the film’s amazingly haunting, layered orchestral score do much to drive the story and, frankly, keep us involved when a less attentive audience might otherwise have dozed off. Ford, whose background is in the world of fashion, seems to take special pleasure in the simplicity of sharply worn clothing or the high-contrast curve of the wood grain on the dash of a 60s automobile. It gives the movie a life beyond what might have been found on the page, a life it needed in order to keep us involved. It’s a quiet and subtle film, one which if embraced has the power to break your heart.