It might be my age-- I'm a 25-year-old child of baby boomers-- but I am completely sick of hearing about Woodstock. My parents weren't even there, but I've spent most of my life fielding stories about the mud, the music, the peace, the love, whatever, all told with the condescending attitude suggesting nothing so amazing will ever happen in my lifetime, ever. Baby boomers are known for their love of navel-gazing, and 40 years after that momentous summer of 69, it seems pretty certain that any superlative that could be applied Woodstock has been more than done.

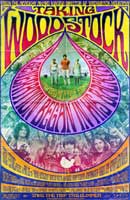

Of course, Ang Lee was growing up in Taiwan during Woodstock, and his frequent collaborator James Schamus was 9 years old that summer. As a result Taking Woodstock is somewhat clear-eyed about its namesake event, focusing on the Catskills Jews and anti-hippie paranoia that greeted the three-day concert rather than the event itself. It's based on the memoirs of Elliot Tiber, the guy who was in the right place at the right time to make the concert possible, but never actually made it to the show. If everyone has spent the 40 years since Woodstock pretending they were there when they weren't, Taking Woodstock stands up proudly for the outsiders.

Unfortunately the movie probably could have used a bit more of the concert's anarchic spirit, as Lee presents the chaotic run-up to the festival in an orderly procession of scenes in which plans are made, characters quietly joke, a few lessons are learned and nothing really happens. 34 years old in 1969, Tiber had been yanked from a relatively freewheeling life in Manhattan's gay underground to help his parents (Imelda Staunton and Henry Goodman) run their decrepit El Monaco hotel. Elliott is also on the local town council, and finds himself in possession of a permit for a music concert just as the organizers of Woodstock are kicked out of neighboring Walkill. Ignoring the protests of local concerned citizens (Jeffrey Dean Morgan among them), Elliott invites the Woodstock crew to Bethel, and convinces neighbor Max Yasgur (Eugene Levy) to let the kids have their concert on his dairy farm-- so long as they clean up after themselves.

The El Monaco is rented out for the season, the hippies stream in by the thousands, and sleepy Bethel is transformed in a way thats secures its spot in history. In his first major movie role, Demetri Martin is charming but somewhat unengaged as Elliott, much more of an observer to the events around him than a main character should be. Even as he struggles to come out to his parents and has a brief dalliance with a burly construction worker, Elliott's story isn't half as interesting as the 6 or 7 supporting characters around him. Jonathan Groff is serene and wonderful as concert promoter Mike Lang, and Liev Schreiber is pitch-perfect as Vilma, the gruff drag queen from New York brought in as security after the Mob shows up to pressure Elliott's parents into sharing their cut of profits. Staunton steals the show as Elliott's mom, a tough Russian Jew who earned the hard knocks that made her as shrew and frugal as she is. A force of nature with a motor mouth, Staunton is a burst of crazy life in a movie that is otherwise mostly content to play by the rules.

Lee's camera does some amazing stuff too, especially an epic tracking shot over thousands of extras on their way to Yasgur's farm, and an extended acid trip sequence that is as beautiful as it is headache-inducing. He also brings out the split screen technique that was so reviled in Hulk but also hearkens back to the original Woodstock documentary; the look is unique and all, but it's unclear what three angles on a specific scene can demonstrate, especially when the scene isn't all that interesting to begin with.

The little bit of nostalgia that does sneak through the cracks is probably provided by the viewer, marveling at the human drama that really did happen, and all the strange coincidences that made it possible. But in its efforts not to view Woodstock through a drug-addled haze, Taking Woodstock fails to find a point of view at all; as fascinating as Tiber's life must have been, from witnessing Stonewall to taking off for San Francisco in the 70s, most of it is left offscreen. It's a gentle and largely enjoyable way to tell a story, but also one that never leaves much of an impression. Lee has said he made this film to get away from the deep drama of his last few efforts, but Taking Woodstock skews so far into the other direction as to become nothing at all.

Staff Writer at CinemaBlend