There are bonds created between women that men may never understand; perhaps the emotional connection between mothers, daughters and sisters is forged when a new generation springs from the former’s womb. At times, these bonds are complicated, even broken, by love, hate, jealousy and death. Volver accessibly explores those bonds and complications that appear foreign to men. Four years after Raimunda (Penélope Cruz) and Sole’s (Lola Dueñas) mother and father died in a tragic fire, their elderly aunt, who lives alone, speaks as if Raimunda and Sole’s mother is still alive and taking care of her in a small Spanish village. After the Aunt’s death, Sole’s mother “appears” to her, while Raimunda and her daughter deal with the untimely death of their pseudo-patriarch.

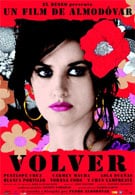

Although Volver seems to have a soap-operatic story, writer/director Pedro Almodóvar avoids most of the melodramatic trappings by maintaining a darkly comedic and honest tone, while Cruz’s attitude keeps the atmosphere light-hearted and optimistic. Whether she is dragging a body into a freezer or singing a delicate song her mother once taught her, the charming and lovable Cruz is enough to pull us through the story’s lulls. Coupled with the lighthearted film score and Almodóvar’s camera that allows the storyline to pour through small Spanish villas and flow over windmill populated landscapes, the film evokes a spirit of Fellini, as oppose to the Spanish surrealists or experimentalists such as Luis Buñuel.

The story line plays second fiddle to the emotional connections of the characters and the strongest relationship comes from Raimunda and her daughter Paula. When Paula accidentally kills her father in a struggle, Raimunda takes on the responsibility of the murder in behavior that is both for the protection of her daughter and testament to her motherhood. Throughout the course of the film, we discover that the relationship between Raimunda and her mother was splintered early on and that Raimunda is trying to avoid that with her own daughter.

Along side the womanly bonds, Almodóvar even has a little fun with contemporary clichés such as the beauty salon gossip shop, which Sole runs out of her home, and frivolous talk shows that are typically marketed toward women. Yet, there is a clear dichotomy in Almodóvar’s eyes as the beauty salon serves as a communal refuge for women and the talk shows destroy trust. It is where Sole and her mother rekindle their relationship, Paula and her grandmother meet for the first time and Raimunda’s mother finally “appears” to her. One the other hand, the talk show, which is referred to as Trash TV, comes close to widening the gap between Raimunda and her mother with its exploitive motives and secret reveals.

Caught up in his own investigation of clichés, Almodóvar slips into the “men are pigs” camp -- dwindling men down to utilitarian roles. From the simple store clerk to the abusive husband, men are a means to an end. While Volver is primarily focused on the women, it’s a shame to see the role of men downgraded to a sketch of generalities. It’s hard to see why the male presence in the film is slighted when it’s the main motivator of the plot and cause of the disintegration of female relationships. Unless, Almodóvar purposefully side stepped answering the question of how men factor into relationships between women. Then again, when you put Cruz on screen for two hours, I doubt most men would notice that they are being snubbed.