The most shocking thing about W. isn’t that it portrays a sitting president as a charismatic simpleton with out of control daddy issues, it’s that the film’s director Oliver Stone actually seems to like George W. Bush. I’m not saying he thinks he’s a good President or that he agrees with well, just about anything Bush has done during his term in office. But it’s impossible to watch W. and not come to the conclusion that at the least, this is a man that Stone sympathizes with. The Dubya (as he’s frequently called by his friends) of Stone’s film is a confused, often well-meaning man in over his head, out of his depth, and completely unaware of his own limitations.

Stone’s approach to Dubya as a lovable shlub is brilliant, enabling him to dodge many of the pitfalls a project like this is fraught with. Even though the movie’s marketing materials seem intent on reducing Bush to a crass running gag, the film itself is never mocking or mean spirited. Bush may be something of a boob, but he’s a lovable boob, perhaps even a harmless one, or would have been a harmless had we the people not been stupid enough to give him the reigns of power. Stone tells his story by mixing fact with wild conjecture. We see re-enacted events which were on the record and thus accurate, as well as a number of things which Stone invents wholesale as a way of getting across his take on the character. Interestingly, it’s in those wholly fabricated scenes that Stone shows the most affection for George. His public persona is often his harshest, in the privacy of his own bedroom Bush comes off as a kind and frequently bewildered man.

Oliver Stone’s approach to the material is the right one, unfortunately his film is a structural disaster. He knows in general how he wants to portray the president, but beyond that Stone has no real theme or goal. He leaps through time, telling different parts of Bush’s story at different places, with nothing of any substance connecting it all together. Many of the biggest moments in the movie serve no purpose, except as a way to let the audience revisit Bush’s greatest hits. For instance, early in the movie Stone hops through time to show us George’s famous pretzel choking incident. We leave an unrelated scene to watch him gag and fall on the floor, and then we’re jumping to something else, with no further mention of Dubya’s near death experience. It’s as if Stone was in a rush when he wrote it, as if he had a list of things he wanted to cover but didn’t have a clear idea of what he was trying to say with any of them, other than “hey, here’s Bush!”

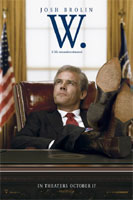

As a character study though, W. is fascinating. Josh Brolin turns in an incredible performance as Dubya, his Bush is spot on. What he does is something more than mimicry, you can see it in his eyes, he’s there searching for George’s soul. He’s a dead ringer for the most powerful man in the world, and Brolin is inside his head. The movie’s other performances come in varying flavors of success. James Cromwell is stately and understated as Dubya’s father George H.W. Bush and Thandie Newton slips so fully into the shrill persona of Condoleezza Rice that she’s completely unrecognizable as herself. Elizabeth Banks on the other hand, is left stranded by Laura Bush, who was written into Stanley Weisner’s script without a personality. It’s a shame too, since her story is, aside from Dubya’s, one of the most baffling. When they meet at a backyard barbecue she’s a spunky teacher devoted to reading, education, and voting Democrat. For a moment, Banks shows fire as she flirts with Bush and teases him about his politics. But that’s the last glimmer of personality we get from her, and we never truly understand how a woman like that ends up married to a right-wing conservative and borderline illiterate. Apparently Stone’s answer is that Laura shuts her mouth and simply does whatever her husband says.

W. ends long before the modern era, with the Iraq war just starting to go sour in the first half of Dubya’s second term. An intense desire to please his father coupled with family connections, slick campaign managers, and an innate ability to connect with people on some primal, beer-drinking buddy level have pushed Bushie into a position he has absolutely no desire to be in, and once he’s there he convinces himself he’s on a mission from God and starts going with his gut. In the process, he’s manipulated by those around him. Cheney ambushes him at lunches, pushing his agenda and Bush, who doesn’t like reading his paperwork, goes along with it. While his advisors talk about complicated issues like empire building and oil, he distills everything into pre-school like concepts and regurgitates them back as “hey let’s go spread freedom.” The Bush of W. is not an evil man, merely a somewhat foolish and fatally naive one, a man who belongs running a baseball team and not sitting in America’s highest office munching on pretzels. Stone’s take on Bush’s character is ultimately flawed, but fascinating. W. is neither as shocking or vilifying as you may be expecting, but it is entertaining.