"Out on the wastes of the Never-Never, that's where the dead men lie. There where the heat-waves dance forever, that's where the dead men lie."

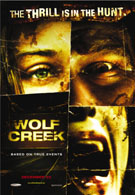

These words were written by Australian poet Barcroft Boake in the late 1890's. The 'Never-Never' he was referring to is the Australian Outback, the country's remote and parched interior where writer-director Greg McLean's first feature, Wolf Creek, takes place. The film was inspired by the case of the Backpacker Murderer, demented Aussie drifter Ivan Milat, who tortured and killed seven tourists between 1989 and 1991. McLean, who had won the Nescafe Big Break Award for a short film in 1992, was so anxious for Wolf Creek not to be, in his words, "messed up", that he produced it himself. It was shown at Sundance and Cannes, then bought by the Weinsteins.

The film begins with fun. In a Spring break-like setting at a Western Australia beach resort, three friends, a man and two women, in their twenties, horse it up in a pool. The man, Ben Mitchell (Nathan Phillips) is Australian, the women, Liz Hunter (Cassandra Magrath) and Kristy Earl (Kestie Morassi), are British. Ben, taking advantage of being on home territory, enthralls his companions with tales of flying saucers and other Outback mysteries. They soon head off to the Never-Never, their objective being Wolfe Creek National Park, site of a huge crater made by a meteorite crashing to Earth thousands of years ago.

Along the way, the trio encounters classic Aussie types: cruder, stubblier versions of Crocodile Dundee. The girls are cordially invited to a gang bang, almost sparking a punch-up in a bah, I mean, bar. Their car breaks down, and they meet Mick Taylor (John Jarratt), a goofy-grinned character who offers help while setting them on edge with his combination of good ol' chap jocularity and vague menace. He's the kind of bloke who jokes about all men from Sydney being gay, and he entertains the three with well-timed quips, his round, ruddy face illuminated by a campfire, a demonic cherub. When, in response to a question, Mick says, "I'd tell you, but then I'd have to kill you," Ben's Adam's Apple starts a-bobbing, the girls' eyes shift uneasily. Mick tows them to his camp, a far-off abandoned mine, and there they go to sleep. What they awaken to, and endure, goes to eleven.

Director McLean uses the environment to advantage in setting up and highlighting the horrors that take place. The red earth, the wide-open skies, a drop of dew that could just as well be the sweat of three terrified travelers, a road sign shot-through by a bullet. Objects, like a dead-looking hand that still harbors life, are not what they seem, and, of course, neither is Mick Taylor. He proves to be a psychopath for whom mutilation and murder, triggered by a desire for intimacy with people's blood and guts, have a quasi-sexual attraction.

The film was deliberately shot to give it a documentary quality. Grainy, a little shaky at times, it's almost a home movie of horror. The creepy music, by Francois Tetaz, enhances without overwhelming. Not that anything would be likely to overshadow the visuals on the screen. The director has claimed that, at one screening, four people ran out and two fainted. "I wanted to make a cinematic hand grenade," were his words. He has succeeded. This first-rate debut is explosive indeed.