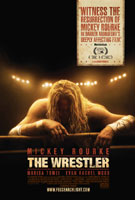

Darren Aronofsky is best known as a director of visually experimental, emotionally complex films like Requiem for a Dream and The Fountain. With The Wrestler, he drops the experimentation and shoots what for him is a quick and dirty film. This is everything which an Aronosfky movie usually is not. The Wrestler, stripped down and raw, hinges almost entirely on the performance of its lead: the lumbering, damaged, Mickey Rourke. Rourke responds by jumping off the top rope and body slamming the movie home.

Randy “The Ram” Robinson was the biggest wrestler in the world, back in the 80s. Now it’s 2009 and while things have changed, mentally he’s stuck there back in good old 1989. He’s still wrestling, even though the money and his audiences have long since vanished. His aging body can no longer take the punishment. To blunt the pain, he pumps himself full of drugs. To make ends meet he wrestles on the weekends and spends his weekdays stocking grocery store shelves. The glamorous life Randy once lived is long gone, but it’s only in the ring, in front of a roaring crowd that he’s not lost and alone. Randy keeps wrestling, because he has nothing else.

Mickey Rourke fits perfectly into Randy’s faded tights; his over muscled, meaty, broken body and mangled face easily embodying the life of a man who has lived so hard that he’s now left drained dry. Rourke hunches his shoulders and clumps through the film, a mirror reflection of Randy’s loneliness and hollow excess. This is one of the great performances of the year, a movie not about wrestling but about a man whose life is completely empty. Randy is a wrestler but he also could have been an investment banker or an ad executive; he’s anyone who’s spent his life so devoted to a single pursuit that he’s long since self-destructed, demolishing everyone and everything else around him.

Randy’s only real connection with the world is a stripper named Cassidy (Marissa Tomei), whom he visits regularly and plies with dollar bills. For both of them, there’s more there than a business transaction. Tomei, who seems to give better performances the more naked she is, really shines here as a stripper on the edge of being past her prime, and starting to feel it. In Randy, she sees her future and she sympathizes with him, sensing perhaps the gentle man lurking inside his scarred hulk.

We, like Cassiday, root for Randy because we know that here is a good man, a man who understands his mistakes but doesn’t know how to fix them. He’s big and broken yes, but he’s also kind, gentle, and the haunted look in Mickey Rourke’s eyes is that of a man desperately reaching out for love. He gets his chance, when a heart attack forces him out of the ring. Deeply shaken, he reaches out to his estranged daughter and takes a real job. He’s good at this new, less glamorous, employment and maybe he’ll even be good at being a father. For the first time in his life, Randy starts to see a future in doing something besides wrestling. Yet he still hears the siren call of the ring and with a few setbacks, we know he might be lured back in, to his death.

The Wrestler is so quiet and so simple that at times it becomes almost overly sentimental. Aronofsky leans so heavily on Rourke, realizing the magic in his performance, that he forgets to give us much else. For fans of bare bones indies that will be enough, but general audiences may be left wanting more than one singular, defining performance. The Wrestler is a good movie, but it lacks style, something which used to be Aronofsky’s specialty. Good as Mickey is, it’s hard not to miss the jaw-dropping experimentation which used to be his trademark. Still perfect casting, the intersection between Rourke’s ruined reality and Randy’s lonely life, makes The Wrestler a must see. Expect to see Mickey on stage holding an Oscar.