Adapting Stephen King's 11.22.63: King Enters The Streaming Age With The 2016 JFK Assassination Miniseries

The first ever direct-to-streaming Stephen King adaptation.

The entertainment world changed forever in 2013 when Netflix debuted House Of Cards – the first ever original series produced directly for a streaming site. The rest is history, and it’s history that I don’t have to explain because everyone reading this has been living it and watching the rise and evolution of the medium. Just about every major studio has its own proprietary subscription service now, and the content is registered by audiences on the same playing field as theatrically released movies and broadcast/cable television.

The last decade has been dubbed the Streaming Age, and Stephen King adaptations have actually been a ubiquitous part of it – with projects based on King stories made as exclusives on many of the major services, including Netflix, Paramount+, Apple TV+, and Shudder. But, before any of those companies got in the game, Hulu was the first one to leap with the miniseries 11.22.63, based on the novel of the same name (albeit with slashes instead of periods) published in 2011.

Admittedly, streaming wasn’t actually the first target for the adaptation, nor was it initially to be made as a miniseries. Before the book was published, Oscar-winning director Jonathan Demme got the rights and started trying to make an 11.22.63 film. In December 2012, the writer/director announced he was no longer working on the project, saying that he and the author “were too apart on what [they] felt should be in and what should be out of the script.”

Sixteen months later, Bad Robot (J.J. Abrams’ production company) entered negotiations to acquire the rights to the book, making plans to develop an adaptation through their deal with Warner Bros. TV – and Hulu entered the picture 17 months after that. With Bridget Carpenter, Stephen King, Bryan Burk, and Abrams as executive producers, it was the most ambitious original programming move made by the streaming service at the time.

With this history, 11.22.63 is automatically a standout title in the history of Stephen King film and television projects – but just how faithful is it to the novel, and how does it compare? Those are (as always) the big questions I get into in this week’s Adapting Stephen King.

What 11.22.63 Is About

Those of you who read my column about the CBS series, Under The Dome, might experience some déjà vu learning the origins of 11/22/63, as there is a notable common denominator between the two tomes: they are both stories that Stephen King started to write early in his career, but he put them aside because of the daunting research required to properly execute the premises. He started Under The Dome in 1976, and it wasn’t completed until 2009; 11/22/63 hit bookshelves in 2011, but it was a book he worked on even before Carrie was published.

Stephen King writes about the many decades it took to get 11/22/63 from story concept to published work in the Afterword of the book, and he adds that the research wasn’t the exclusive reason why he had trouble getting it done. He was trying to create a book about the tragic assassination of President John F. Kennedy less than a decade after the event occurred, and the memory remained too painful for him to write through. He explains,

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

I originally tried to write this book way back in 1972. I dropped the project because the research it would involve seemed far too daunting for a man who was teaching full-time. There was another reason: even nine years after the deed, the wound was still too fresh. I’m glad I waited.

The novel could also be called a sibling to The Dead Zone, as their core ideas are arguably two sides of the same coin (narratively speaking). The 1979 novel imagines a circumstance where a man is in the right for carrying out a political assassination, and at one point poses the question, “If you could jump into a time machine and go back to 1932, would you kill Hitler?” 11/22/63 asks the question, “If you could jump into a time machine and go back to 1963, would you save Kennedy?” – and it’s a much more literal approach.

Jake Epping is a compassionate but emotionally congested high school English teacher who lives in the town of Lisbon Falls, Maine, and on one fateful day in 2011 he is let in on a world-changing secret by Al Templeton, the owner of a local diner that the protagonist frequents. Al is dying from cancer, and before he passes away he decides to show Jake a special area of his restaurant’s pantry that somehow serves as an invisible doorway to September 9, 1958 at 11:58am EST. You can go through, change the past, and then come back to an altered future where only two minutes have passed. But as soon as you go through again, the timeline resets.

Jake learns that Al has had a primary mission using this rabbit hole: to stop Lee Harvey Oswald and save the life of President John F. Kennedy – completely changing world history, presumably for the better. Though reluctant, the English teacher agrees to carry on his friend’s work, and he goes back in time, taking on the name George Amberson.

With more than two years to wait until Lee Harvey Oswald returns to the United States after defecting to the Soviet Union, and more than five years to wait until the assassination, Jake makes a life for himself in the late 1950s/early 1960s, but as he tries to change the life of one of his GED students and complete his ultimate task, he understands that the past protects itself, and it tries to throw horrible obstacles in his way to preserve history as we know it.

How The 11.22.63 Miniseries Differs From Stephen King’s Book

My notes comparing 11/22/63 and 11.22.63 side-by-side are as long as this entire feature, so it’s not really possible for me to highlight every single difference between the book and the miniseries. The adaptation is mostly faithful to the source material, hitting all of the most important plot points in the story, but there are some major changes – including both additions and subtractions.

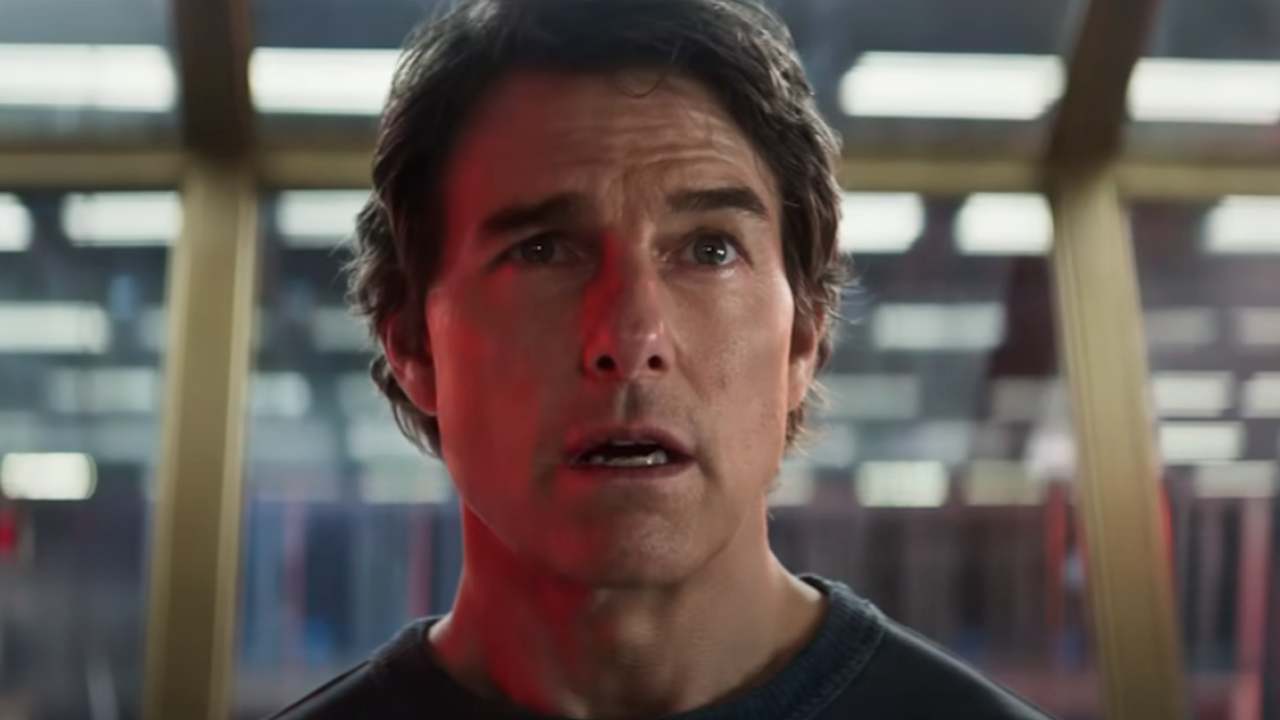

One standout alteration is introduced early, and ends up having a big impact on the story: while the rabbit hole lets a person step into September 9, 1958 in the book, 11.22.63 changes the date to October 21, 1960. This is an effort made to tighten things up and let the story get to where it’s going faster, but it also lowers the stakes for the protagonist as far as Jake (James Franco) potentially aborting his mission and starting over (The extra two years is a lot of time to take in consideration when it comes to the character making the decision whether or not to hit the reset button when things start to go really bad).

Cutting these years out also means skipping over significant sections of Stephen King’s story, like Jake living in Florida for a spell and needing to get out of the state fast after being a bit too “lucky” making sports bets with dangerous people.

Keeping on the subject of places the character doesn’t go, also excised from the miniseries, is a place that is infamous among Constant Readers: Derry, Maine. The adaptation still has Jake’s GED student, Harry Dunning (Leon Rippy), and features Jake’s attempt to stop Harry’s homicidal father, Frank Dunning (Josh Duhamel), from murdering Harry’s mother and siblings, but their home is in Holden, Kentucky instead of Derry in the show. With this detail changed, there is also no mention of The Murder Place – the book that Jake starts writing about the haunted town as part of his cover story.

Far and away the biggest change made by 11.22.63 is the treatment of Bill Turcotte (George MacKay). The circumstances under which Jake meets him are the same, with Bill having his own desire for revenge against Frank Dunning and interrupting Jake’s plans – but the novel sees Bill’s story come to an end in the Dunning house when he suffers a heart attack shortly after killing Frank.

In the series the character is made to be much younger, and he ends up learning that Jake is a time-traveler. He travels with Jake to Texas under the guise of being the protagonist’s brother to help keep an eye on Lee Harvey Oswald (Daniel Webber), but he ends up becoming a liability instead of an asset. Jake has to lock him up in a mental hospital so that nobody will believe his claims about time travelers and assassination attempts. Later, Jake goes to him searching for answers after a horrible beating leaves Jake with short term memory loss, but Bill kills himself by leaping out of a window.

Finally, there is the Yellow Card Man (Kevin J. O'Connor). In the book, there is a key section where Jake has a conversation with this stranger and learns about the much broader consequences of his time traveling. The Yellow Card Man is a human who is essentially stationed at the rabbit hole and has a wholly different perspective on time travel. He explains that each trip through the portal creates a new string in reality and leaves a residue – and there is more residue left behind by massive changes to history. With enough bundled strings and residue gunking up the machine, the machine ceases to work, and it’s essentially his job to warn time travelers about this danger.

None of this is in the miniseries. Jake does have an extended encounter with the Yellow Card Man, but it takes place in Texas instead of by the rabbit hole, and the character is changed to be a lost time traveler who is tortured by the accidental death of his daughter and can’t alter the past.

Is It Worthy Of The King?

The total runtime of 11.22.63’s eight episodes is over seven hours, which made it the longest miniseries adaptation of a Stephen King book at the time that it aired – and yet it still isn’t able to capture so much of what is great about the novel. It’s in many ways a love letter to the art of teaching, and while some of the most powerful material in the text is about the community that Jake becomes a part of while teaching high school in Jodie, Texas, the Hulu show doesn’t engage with it as much as it should.

Beyond that, though, it’s a fitting and thrilling take on King’s book, with passionate performances from James Franco as Jake, Chris Cooper as Al Templeton, and Sarah Gadon as Sadie, the love of Jake’s life. The expansion of Bill’s role distracts the material in some ways, but it proves to be a brilliant source of conflict (fueled by a lot of chaotic energy in George MacKay’s performance), and the end of his arc is a terrific and memorable gut punch.

Its existence as the first direct-to-streaming adaptation of a Stephen King book cements a certain legacy, but it also happens to be one of the best miniseries produced to date, and it set a high bar to be reached by future projects, including Hulu’s Castle Rock, Paramount+’s The Stand, and Apple TV+’s Lisey’s Story (all of which will be getting their own column in the coming weeks).

How To Watch The 11.22.63 Miniseries

One of the nice things about exclusive streaming shows is that they, theoretically, will forever exist on the service on which they premiered – and that’s certainly held true for 11.22.63. The show in its entirety has been available with a Hulu subscription ever since its finale launched online. What’s also great, however, is that the term “exclusive” is a bit lax in this instance, as there are other available options to watch. A Blu-ray was released by Warner Bros. a few months after the adaptation aired, and you can purchase individual episodes or the full miniseries via Amazon Prime Video, Vudu, Google Play, and Apple.

For next week’s Adapting Stephen King, I’ll be moving back to the CinemaBlend Movies section for a dive into Tod Williams’ Cell, based on the 2006 novel. Look for the feature next Wednesday, and click through the banners below to find all of the past installments of this column.

Eric Eisenberg is the Assistant Managing Editor at CinemaBlend. After graduating Boston University and earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism, he took a part-time job as a staff writer for CinemaBlend, and after six months was offered the opportunity to move to Los Angeles and take on a newly created West Coast Editor position. Over a decade later, he's continuing to advance his interests and expertise. In addition to conducting filmmaker interviews and contributing to the news and feature content of the site, Eric also oversees the Movie Reviews section, writes the the weekend box office report (published Sundays), and is the site's resident Stephen King expert. He has two King-related columns.