Disney Parks Was Supposed To Get Its Own Ski Resort: The Story Behind Why It Never Happened

Walt Disney had many resort ideas after Disneyland, and one would have given us a Disney ski resort.

When Walt Disney opened Disneyland in 1955, it was unlike anything the world had ever seen before. Walt himself was clearly happy with what he’d made because almost as soon as it was done, his attention turned to even more resort-style projects. What would become Walt Disney World is, of course, the most well-known, but that wasn’t the only idea Walt had following Disneyland. At the same time he was scouting land in Florida, he also had his eye on a ski resort project in California. Disney’s Mineral Ski Resort would have been a truly unique experience, though it was one we never saw.

There are as many Disney theme park ideas that never happened as there are Disney theme parks that exist today, but Mineral King, if it had become a reality, would be truly unique among them. This is the story of what Mineral King was going to be and why it never happened.

Mineral King: Disneyland In The Snow

In 1960, five years after Disneyland had been proven a success, Walt Disney was asked to run the opening and closing ceremonies of the Winter Olympic Games at Squaw Valley, California. This resulted in Walt spending a lot of time around winter sports. He’d been at least a somewhat regular snow skier since the 1930s, so he enjoyed the sport already, and it seems that as he began to work on the Olympics, the idea of a permanent Disney ski resort began to percolate in his mind.

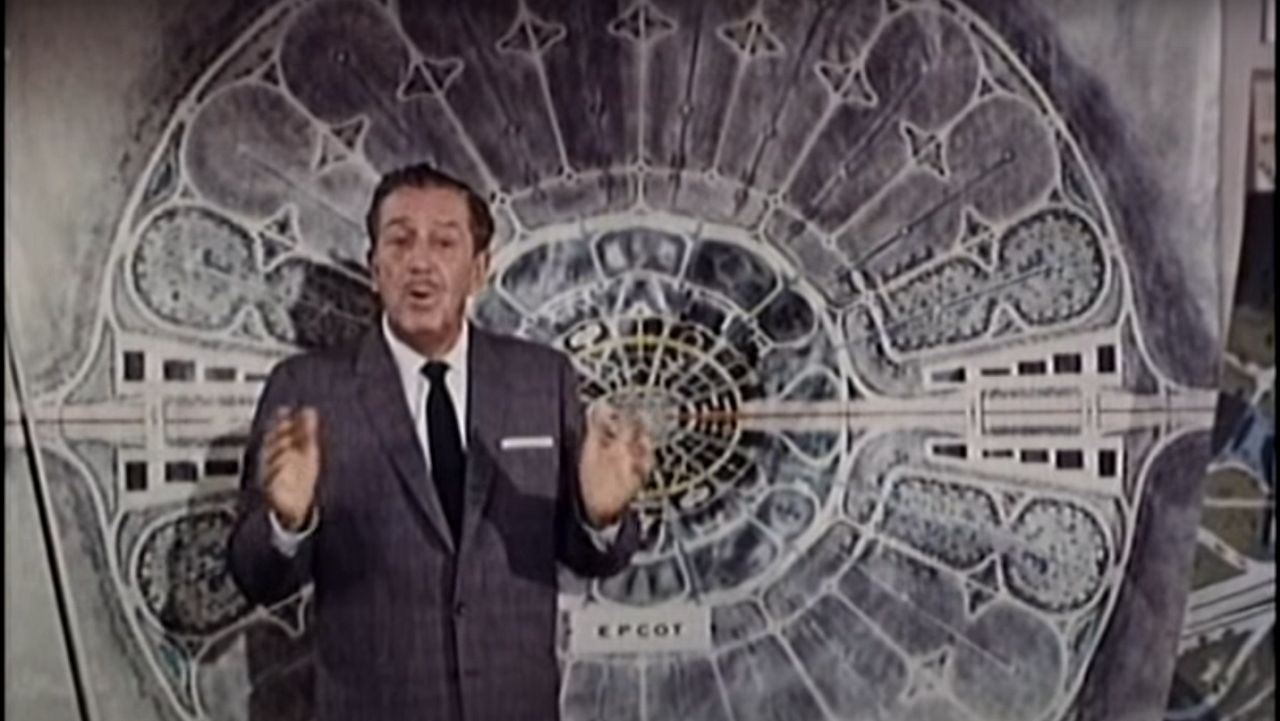

Eventually the idea became an active project, and Disney went looking for a place to build his ski resort. He found Mineral King, a part of the Sequoia National Forest a few hours north of Los Angeles, and about equally south of San Francisco. In 1965, the U.S. Forest Service invited proposals for a ski resort complex in the area. In December 1965, a month after the press conference where it was confirmed that Disney had been buying swampland in Florida to construct his “East Coast Disneyland,” the U.S. Forest Service awarded Disney the right to develop the land.

Significant development would certainly be needed. There weren’t even paved roads going all the way to where Disney envisioned his Alpine Village Ski Resort would be built. There was also the question of what to do with the resort during the months of the year when there was no snow, as the cost of building the resort would necessitate it being open year-round.

Skiing would be a major winter attraction, of course, with over a dozen ski lifts initially planned, but an ice rink was also part of the development, as well as tobogganing and dogsled rides. In the summer, guests could visit to take part in swimming, horseback riding, tennis and hiking.

Multiple hotels and restaurants were planned, and inside one of them would be the most “Disneyland” touch of all. Walt had the idea for an animatronic band made up of bears that would perform while people ate. The idea would become the Country Bear Jamboree, which would eventually become an opening day attraction at Magic Kingdom and be built at Disneyland as well.

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

The Battle Over Disney's Ski Resort Plan

When Walt announced his Florida Project, he was welcomed to the Sunshine State with open arms. Florida went as far as to create a special district to oversee Walt Disney World so the resort would have greater control over itself.

This was the case for Mineral King as well, at least at the state level. Governors Pat Brown, and later Ronald Reagan, both supported the plan strongly for the tourism dollars and jobs that it would create. Brown helped earmark money to help pay for some of the construction, including the building and widening of roads.

However, environmental groups, most notably the Sierra Club, felt differently. They objected to the idea of a Disney resort in the middle of Sequoia National Forrest. They argued that the development that would need to be done, including the building of miles of new road for cars, would destroy the natural beauty of the area.

Walt Disney argued that the natural beauty of the area was exactly what he wanted people to experience, and so he had no interest in destroying it. Walt was inspired by the town of Zermatt in Switzerland, which he had visited during the production of the film Third Man on the Mountain, which was an area free of combustion engines. Walt envisioned a similar design for Mineral King where guests would park their cars several miles away and be transported to the resort area by some form of railway.

In September 1966, there was a press conference to officially announce the Mineral King project, similar to the one that had happened in Florida a year earlier for Disney World. It was reported at the time that Walt Disney did not look well. Two months later, Walt died.

The Death Of Walt Disney, And Lawsuits, End The Mineral King Project

The death of Walt Disney obviously had major ramifications for the company, but chief among them was that all attention turned to Disney World. Walt’s brother Roy O. Disney had been planning to retire when Walt died. Instead, he became CEO, with the singular goal of seeing the Florida project completed.

Work did continue on the Mineral King project as well, but as Disney World's construction began to see its costs go up, the plans for Mineral King began to shrink. Most of the new developments regarding the project took place in courtrooms. The Sierra Club filed a lawsuit against the project. In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the suit, but the Sierra Club then followed up with an amended suit. By this time, both Roy and Walt had passed away, and there just wasn't the interest within the company to continue the fight.

In November 1978, Mineral King officially became part of Sequoia National Park, ensuring the land’s protection from future development. By then, Disney had long moved on from Mineral King, so it was never going to happen anyway. Maybe it should not have happened, as the argument against it isn't without merit, but it's impossible not to wonder just what sort of a place it could have been.

CinemaBlend’s resident theme park junkie and amateur Disney historian, Dirk began writing for CinemaBlend as a freelancer in 2015 before joining the site full-time in 2018. He has previously held positions as a Staff Writer and Games Editor, but has more recently transformed his true passion into his job as the head of the site's Theme Park section. He has previously done freelance work for various gaming and technology sites. Prior to starting his second career as a writer he worked for 12 years in sales for various companies within the consumer electronics industry. He has a degree in political science from the University of California, Davis. Is an armchair Imagineer, Epcot Stan, Future Club 33 Member.